![]()

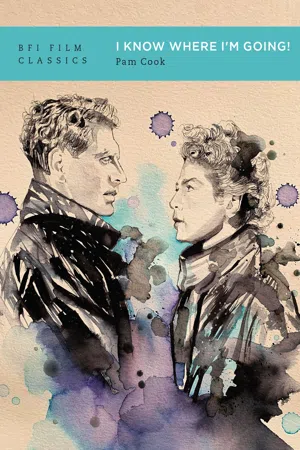

I Know Where I’m Going!

After A Canterbury Tale … we were not quite sure where we were going.8

I Know Where I’m Going! is a film of extraordinary beauty and emotional power. Writing about it is an adventure and a challenge; it means so much to so many people – to those members of Powell and Pressburger’s company The Archers who participated in its making in 1944, and to others, like myself, who have fallen under its spell more recently. Magically, it changes lives, inspires new directions in those who see it; a simple love story, it draws us into the dark, dangerous waters of sexual desire and death; like myth, it works on unconscious levels difficult to contain through rational analysis.9 To someone like me, who grew up in post-war Britain, with its egalitarian rhetoric and idealistic vision of a new, modern nation,10 I Know Where I’m Going! (affectionately known as IKWIG) carries additional resonances. The very title, with its tease in the tail, the emphatic exclamation mark that warns against taking such a confident assertion at face value, is tinged with irony.

This is a film about an interrupted journey, during which travellers are compelled to change direction and revise priorities. One can imagine the wry glint in the film-makers’ eyes: ‘Ah, yes, you think you know, but …’ Several of those involved in the production were European émigrés who had experienced enforced, and in some cases traumatic, digressions and delays in life’s journey. For Emeric Pressburger, who wrote the script of IKWIG in a matter of days from an idea he had long cherished, the concept of life-shattering diversions from a planned route must have seemed particularly poignant.11 The film itself was a detour in The Archers’ itinerary, an unscheduled stop between A Canterbury Tale (1944) and A Matter of Life and Death (1946). Its anti-materialist message – in effect, a critique of profiteering – partly reflected the context of wartime restrictions in which it was made: the unavailability of Technicolor stock had delayed the production of the ambitious propaganda piece A Matter of Life and Death, commissioned by Jack Beddington of the Ministry of Information in the interests of improving post-war Anglo-American relations.12 In 1944, the war may well have been over bar the shouting, but the celebration of a post-war consumer boom at this stage seemed, to The Archers at least, premature and inappropriate.

A sense of direction: Joan on the Glasgow Express

There’s an element of romantic nostalgia in this – an unwillingness, perhaps, to leave the war behind and to look confidently towards the future. Nostalgia for the war, and the clear-cut ideals for which it was fought, is not so surprising at this point in The Archers’ career. After a string of box-office successes, A Canterbury Tale had been met by a cool reception from audiences and critics – mostly, it seems, because of the perversity of the peculiar glue-pouring Culpepper, but also because of its complicated, meandering plot. Powell and Pressburger were unsure what direction to take next. The temporary shelving of A Matter of Life and Death created a hiatus; this elaborate black-and-white and Technicolor fantasy made way for an apparently simple, straightforward narrative, an intense love story that would link the idealism of their previous film with the life-and-death romance of the one that was to follow.13

A simple love story: Roger Livesey as Torquil and Wendy Hiller as Joan

On the face of it, the storyline is reassuringly transparent. Joan Webster (Wendy Hiller), a strong-willed, materialistic young woman who works for Consolidated Chemical Industries, travels from Manchester to Scotland with the intention of marrying her wealthy boss, Sir Robert Bellinger (Norman Shelley), on the island of Kiloran, which he has rented for the duration of the war. When she arrives at Port Erraig on Mull, a storm blows up, preventing her from crossing by boat to the island. She meets Torquil MacNeil (Roger Livesey), a handsome Scottish naval lieutenant who hopes to spend his leave on Kiloran, and they end up taking refuge at Erraig House, owned by Torquil’s childhood friend Catriona MacLaine (Pamela Brown). Due to an ancient feud, the MacLaines laid a curse on the MacNeils which still terrifies Torquil, who reveals himself to be the impoverished Laird of Kiloran, forced to lease his island to rich foreigners in order to survive. Joan and Torquil are immediately attracted to one another, which makes Joan even more determined to cross to the island as soon as possible, in spite of warnings from the locals about the perilous conditions and the danger posed by the Corryvreckan whirlpool.

Fast forward: the Glasgow Express speeds towards Scotland

Despite herself, Joan is increasingly seduced by the colourful traditions and simple values of the Highlanders’ way of life, and by Torquil himself. In a last-ditch attempt to escape her feelings for the Scotsman, Joan hires Kenny (Murdo Morrison), a young, inexperienced boatman, to take her across the turbulent seas to her fiancé. Torquil, unable to persuade her to change her mind, insists on going with them. The storm gets worse, the engine fails and the boat is dragged to the edge of the whirlpool, only just managing to veer away when Torquil starts the engine. Chastened by their experience, the couple return to Erraig House, and when the storm subsides, Joan sets off for Kiloran once more, but not before she and Torquil have exchanged a passionate farewell kiss. Torquil crosses the threshold of Moy Castle to confront the MacLaine curse, where Joan, who has changed her mind about marrying Sir Robert, returns to find him. The pair embrace, declaring their undying love for one another.

This theme of star-crossed lovers with its ‘love conquers all’ moral is not so far removed from previous productions such as The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943) and A Canterbury Tale. It was also the mainspring of the delayed extravaganza A Matter of Life and Death. However, IKWIG was heralded as a more conventional enterprise than The Archers’ other films, and it could be seen as a bridging exercise – an attempt to regain lost ground with critics and audiences, and to mark time until the more complex project could go into production. As it turned out, IKWIG was a critical and commercial success, though many still found parts of the story confusing, despite its more classical structure.14 However, it is far from being a minor transition piece bracketed between two wayward masterpieces. This is a film that encapsulates the memories, working ethos and artistic aspirations of a remarkable group of film-makers at a unique moment in British cultural history.

Cultural exchanges: British cinema and Europe

The formation of Powell and Pressburger’s company The Archers in 1942 inaugurated a cycle of productions distinguished by technical ingenuity, adventurous aesthetics and box-office appeal. The pair’s collaboration had begun earlier, in 1938, when they were brought together by Alexander Korda, head of London Films, to develop a subject suitable for German actor Conrad Veidt. The result was The Spy in Black (1939), an espionage film set in Scotland during World War I, featuring an impossible love affair between Veidt’s German submarine captain and a British agent played by Valerie Hobson, which was a huge commercial success in Britain and the US.15 As usual, Korda, himself an Hungarian émigré, employed an international team of creative personnel, and besides Pressburger and Veidt, other Europeans such as production designer Vincent Korda and composer Miklós Rózsa worked on the film. Alexander Korda could be said to have been a formative influence on Powell and Pressburger in this respect: The Archers’ productions also brought together a cosmopolitan repertory company with a strong European flavour.

The Spy in Black (1939): Conrad Veidt and Valerie Hobson

Korda’s policy of importing European personnel was not an isolated example. Since the 1920s, British producers (and, indeed, their Hollywood counterparts) had looked to Europe, and particularly to Germany, for experienced technicians trained at well-equipped studios such as UFA (Universum-Film Aktiengesellschaft), with their state-of-the-art facilities and dedication to aesthetic innovation. Michael Balcon, for instance, head of Gainsborough and Gaumont-British from the mid-20s to the mid-30s, initiated a series of co-productions with European companies, and actively promoted a programme of cultural exchange by inviting respected continentals to work in the British film industry. This venture coincided with the ‘Film Europe’ movement, an attempt during the late 1920s and early 30s to establish a pan-European cartel which would be capable of breaking the Hollywood stranglehold on world markets. Subsequently, after the Nazi accession to power in 1933, there was a further influx of European exiles into the British industry.16 Many of the recruited continentals, particularly in the areas of cinematography and production design, established long-term careers in Britain and had a far-reaching, lasting influence – despite the xenophobic response from those who mistakenly perceived their arrival as a foreign invasion.

If the European exiles during this period were treated with suspicion by some, they were regarded as an élite by many, who welcomed the expertise that they offered to a British film industry that aspired to the artistic accomplishment and international success of the European and Hollywood industries, yet lacked the facilities and the technical know-how to achieve them. Britain stood to gain much from the process of cultural exchange, while some of the continental technicians who settled here attained levels of power and autonomy far greater than had been available to them in Europe. German set designer Alfred Junge, for example, a regular member of The Archers’ team between 1943 and 1947, arrived in Britain in the late 1920s, and in 1932 secured a contract as supervising art director at Gaumont-British which gave him unprecedented control over almost all aspects of visual design, including cinematography.

The success of cultural exchange in invigorating the British film industry and strengthening its position in world markets remains to be fully assessed. But the striking features of the strategy are none the less interesting: the emphasis on international co-operation, on craftsmanship, and on collaboration between teams of talented workers implies a less hierarchical model of the production process than those we are accustomed to these days.17 It was in this collaborative spirit that the Englishman Michael Powell and the Hungarian Emeric Pressburger formed The Archers. However, the flowering of that partnership depended to some extent on structural changes affecting the British film industry during the 1940s.

J. Arthur Rank, IPL and The Archers

Powell and Pressburger’s new company was officially announced on 7 January 1942. The pair agreed to share equally the creative responsibility and the financial rewards for their films, all of which would display the end title ‘Written, Produced and Directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’.18 Following meetings between Powell, Pressburger and flour magnate-turned-film tycoon J. Arthur Rank, The Archers won an extraordinary deal whereby they were to produce two pictures for Rank in the next year, at their own discretion, with £15,000 per picture and 10 per cent of the net profit. Later this ...