- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

‘Beguiling.’ The Times

‘Compelling.’ Wall Street Journal

‘A vivid portrait.’ Daily Mail

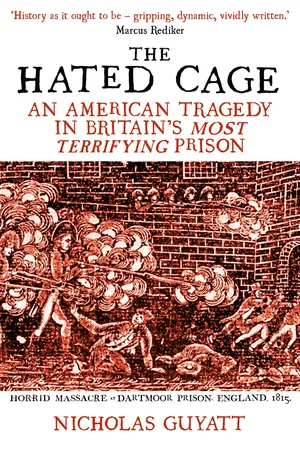

Buried in the history of our most famous jail, a unique story of captivity, violence and race.

It's 1812 – Britain and America are at war. British redcoats torch the White House and six thousand American sailors languish in the world’s largest prisoner-of-war camp, Dartmoor. A myriad of races and backgrounds, some are as young as thirteen.

Known as the ‘hated cage’, Dartmoor was designed to break its inmates, body and spirit. Yet, somehow, life continued to flourish behind its tall granite walls. Prisoners taught each other foreign languages and science, put on plays and staged boxing matches. In daring efforts to escape they lived every prison-break cliché – how to hide the tunnel entrances, what to do with the earth, which disguises might pass…

Drawing on meticulous research, The Hated Cage documents the extraordinary communities these men built within the prison – and the terrible massacre that destroyed these worlds.

‘This is history as it ought to be – gripping, dynamic, vividly written.’ Marcus Rediker

‘Compelling.’ Wall Street Journal

‘A vivid portrait.’ Daily Mail

Buried in the history of our most famous jail, a unique story of captivity, violence and race.

It's 1812 – Britain and America are at war. British redcoats torch the White House and six thousand American sailors languish in the world’s largest prisoner-of-war camp, Dartmoor. A myriad of races and backgrounds, some are as young as thirteen.

Known as the ‘hated cage’, Dartmoor was designed to break its inmates, body and spirit. Yet, somehow, life continued to flourish behind its tall granite walls. Prisoners taught each other foreign languages and science, put on plays and staged boxing matches. In daring efforts to escape they lived every prison-break cliché – how to hide the tunnel entrances, what to do with the earth, which disguises might pass…

Drawing on meticulous research, The Hated Cage documents the extraordinary communities these men built within the prison – and the terrible massacre that destroyed these worlds.

‘This is history as it ought to be – gripping, dynamic, vividly written.’ Marcus Rediker

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Hated Cage by Nicholas Guyatt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

King Dick at Vienna

AFTER WHAT HAPPENED AT DARTMOOR, PLENTY OF PEOPLE would tell stories about King Dick. He may have told some himself, though we know him entirely through the things white people said about him: partial, contradictory, outlandish. Of his early years we know almost nothing, though after his capture near Bordeaux in the spring of 1814 on an American schooner—or was it French?—he was asked to give his name, age, and place of birth. The British clerk who surveyed the new prisoner wrote ‘Richard Crafus’ in the first column. He judged Dick’s height to be six feet, three and a quarter inches, remarkable even for a man who hadn’t spent his career among the diminutive breed of sailors. Dick was twenty-three years old, or so he said, which would place his birth around 1790—just after George Washington became the first president of the United States. And Dick told the clerk he was from Vienna, a small town in Dorchester County on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.1

We don’t know if Dick was born into slavery or freedom, though the former is much more likely. In 1790, the year of the first federal census, around 90 percent of Maryland’s Black inhabitants were enslaved. Although the state’s free Black population increased in subsequent decades, the Eastern Shore remained tightly in slavery’s grip until the Civil War. It also produced two of the greatest abolitionists in American history. Frederick Douglass grew up in Talbot County, around thirty miles north of Vienna. Harriet Tubman spent her childhood just twenty miles to the west of Dick’s hometown. Born a generation later, in 1818 and 1820, Douglass and Tubman became famous not only for their courage but also for their mobility. After her daring escape from Maryland to Philadelphia in 1849, Tubman made at least nineteen subsequent visits to the South to smuggle out friends, relatives, and strangers—hundreds of people in total. Douglass, who fled from Maryland to New England in 1838, was in constant motion as an antislavery lecturer and activist.2

Given their spectacular careers, it’s easy to overlook the fact that Douglass and Tubman came from a desperately confining place. In their early years, they were separated from their closest family members, hired out among the relatives and associates of their owners, and beaten for their acts of defiance and self-expression. When he paid a visit to Baltimore in 1877, a lifetime away from his brutal youth, Douglass cheerfully performed the role of native son: ‘I am an Eastern Shoreman,’ he told the crowds. ‘Eastern Shore corn and Eastern Shore pork gave me my muscle.’ But Americans knew from his speeches and his celebrated narratives that the Eastern Shore had been a hard training ground. It was a place from which most enslaved people would never escape and to which runaways would never return.3

In Vienna, at least, Dick saw many comings and goings. The Nanticoke River brought ships up from the Chesapeake and the vast oceans beyond. Captains presented their credentials at the Custom House, emptying cargoes and collecting tobacco from the surrounding plantations. A small shipyard sat on the river’s edge, launching sloops and schooners into the thriving coastal trade. Most African Americans in and around the town were employed in manual labour: picking tobacco, tending livestock, building and loading ships. The seasonal nature of work meant that children would be hired out long before they became adults. Some were sold to new masters, though the terrors of being cast into the expanding cotton belt of the lower South were a greater threat to Douglass’s and Tubman’s generation than to Dick’s. An African American born into slavery in Vienna in 1790 might have expected to end her life in the same situation, inhabiting a world in which the colour line was indelible. But this would not be Dick’s story.

When Frederick Douglass described his early life, he recalled the dread that accompanied a child’s realisation of what slavery really meant. He remembered the cold: with no shoes, trousers, or jacket, he would steal a sack used for carrying corn, crawl into it, and sleep with his head and legs poking out of the bag. (His feet were so cracked from the cold ‘that the pen with which I am writing might be laid in the gashes’.) Like Douglass, the young Dick would have seen the casual violence which was never far from the surface of slavery. He would also have settled into a worldview in which white people presided easily and inexplicably over Black. But in the autumn of 1796, something remarkable happened in Vienna which challenged the grim certainties of Dick’s world. The region had produced a record crop of Indian corn, a mainstay of the coastal trade and one of the commodities which fuelled American trade with Europe. There was so much of the stuff in Vienna that word had spread throughout the Chesapeake that corn could be had at a good price there. One sea captain from Massachusetts, recently arrived in Norfolk, Virginia, decided to investigate. He had never seen Vienna before, and no one in Vienna had ever seen anything quite like him. His name was Paul Cuffe.4

As Cuffe’s ship, the Ranger, moved slowly up the Nanticoke River, people near the shore looked on with astonishment. It was no surprise to see Black sailors on a schooner; African Americans were a mainstay of merchant crews during the early decades of the United States. But an observer on the banks of the Nanticoke would have noticed a great many Black sailors aboard the Ranger. In fact, the ship was entirely crewed by Black people, including its captain. ‘A vessel owned and commanded by a black man,’ Cuffe later wrote, ‘and manned with a crew of the same complexion, was unprecedented and surprising.’ As Cuffe remembered it, the white population of Vienna was ‘filled with astonishment and alarm’. Surely, an all-Black crew would not risk a journey into the maw of slavery simply to find a bargain. Were they lost? Had they come to start an uprising among the enslaved people of the region?5

Paul Cuffe would become one of the most celebrated African Americans in the early United States. His father, Kofi, had been enslaved in Ghana in the 1720s, sold to a Quaker merchant in Massachusetts, and eventually freed in the mid-1740s. Cuffe’s mother, Ruth Moses, was a Wampanoag Indian from Martha’s Vineyard. Kofi and Ruth had fallen in love and were married in 1746, then built a life for themselves on Cuttyhunk Island, a small strip of land between the Vineyard and the mainland. Kofi and Ruth owned and managed property, but their principal interest was the sea: they repaired boats, ferried people and goods from the islands to the shore, and became modest players in the coastal trade. All ten of their children—four sons and six daughters—took up the family business, though Paul Cuffe, born in 1759, stood out from the rest. As a child he learned to repair and then to build boats, and when he was old enough he went to sea himself. After voyaging to Newfoundland, the West Indies, and Mexico, Cuffe realised that he could be more than just a sailor. He wanted to be a captain, and more than that—he wanted to own the ships he commanded.6

Cuffe and his siblings did well in the American Revolution, running daring raids through the British blockade which had severed the Quaker communities of Nantucket and the Vineyard from the shore. But Cuffe wanted to expand the Revolution’s promise to encompass equality for everyone. In 1780, when a state tax collector appeared at the Cuffe residence, Paul and his brother John reminded him that they were currently barred from voting in state elections, despite the cries of ‘no taxation without representation’ which had animated the Revolution. The collector, inflicting ‘many vexations’ on the Cuffes, eventually forced them to pay up. Paul and John then presented a petition to the state legislature arguing that if Massachusetts expected free Blacks to pay taxes it must grant them ‘all the privileges belonging to citizens’. The battle for Black citizenship in the United States was just beginning. When Cuffe died in 1817, the ‘privileges’ he had claimed under the banner of the American Revolution were far from secure even in Massachusetts. But Paul Cuffe never limited himself to reminding white people of their inconsistencies or pleading with legislators and neighbours for equal treatment. As he bought and sold ships and recruited sailors of colour to crew them, he was determined to shape his own destiny.7

Although the white residents of Vienna had never seen a ship crewed entirely by Black people, images of Black empowerment were a mainstay of their nightmares. In 1791, in the French Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue, hundreds of thousands of enslaved people had risen up against white enslavers whose grip on power had previously seemed unshakable. In a matter of weeks, Saint-Domingue’s towns were under attack and its sugar fields were ablaze. Hundreds of planters fled—many with their enslaved people—to American cities along the Eastern Seaboard. White people throughout the United States fretted about revolutionary contagion from these ‘West Indian slaves’; in towns like Vienna, Haiti posed troubling questions about the stability of a slave system which had previously seemed secure. In the 1790s, every slave state passed a ban on the external slave trade, convinced that the numbers and proportion of enslaved people on the American mainland were dangerously high. Rumours of insurrection moved throughout the waterways of the Chesapeake, disrupting the harsh calm on which enslavers had previously relied. Paul Cuffe knew that his arrival in Vienna would stun the locals, but he made the trip anyway. He had long since decided that he would live his life on his own terms.8

The white residents of Vienna initially refused to let the Ranger tie up at the wharf. As Cuffe remembered it, they were ‘struck with apprehensions of the injurious effects which such circumstances would have on the minds of their slaves, suspecting that [Cuffe] secretly wished to kindle the spirit of rebellion and excite a destructive revolt among them.’ Understanding their anxieties, Cuffe chose to ‘combine prudence with resolution’. He presented his paperwork at the Custom House and announced his desire to trade. He then returned to his ship, ordering the crew to behave with ‘a conciliating propriety’ while they waited for Vienna to choose profit over prejudice. Within a few days, he was permitted to sell his goods and inspect the town’s impressive store of Indian corn. Within a week or two, he was receiving invitations to dinner from local notables, who treated him and his crew ‘with respect and even kindness’. After three weeks, Cuffe had emptied his hold and restocked the Ranger with three thousand bushels of corn. He sailed back to Norfolk, cleared a thousand dollars in profit, and further expanded his maritime empire.9

In 1796, the six-year-old Dick would have been among the first enslaved people to encounter Paul Cuffe’s remarkable example of Black self-reliance. The Ranger and its successors in Cuffe’s fleet would become a regular sight off the coast of the mid-Atlantic in the late 1790s and 1800s, and Cuffe’s thoughts soon turned to an even bigger prize: trade with the new Black colony of Sierra Leone, on the west coast of Africa. But when he wrote up his experiences in 1811, he lingered on the sensation he had created among Vienna’s white population. For the Black onlookers who crowded the banks of the Nanticoke River and gawped at the Ranger and its crew, the effect was no less profound. Enslaved people saw in Paul Cuffe possibilities which seemed unthinkable before his arrival. At some point in the ensuing years, Dick broke away from Vienna and did what Paul Cuffe had shown him Black people could do: he went to sea.

1.

A Seafaring Life

ON A GLOOMY APRIL MORNING IN 1813, THE AMERICAN SAILORS held prisoner aboard the British prison hulk Hector awoke to what should have been good news: they were ordered to pack their belongings and leave the ship. The Hector was moored on the outskirts of Plymouth on Britain’s south coast, one of the busiest and most important naval bases in the empire. Some had been in British custody for six months already, captured at sea soon after the United States declared war on Britain in June 1812. The Hector had served Britain with distinction during the American Revolution and the first years of the conflict with Napoleon Bonaparte. Since 1806, it had been lashed to the shore in its current spot, filling up first with French prisoners and now with Americans. When the weather allowed, the prisoners might spend some of their days on deck before being counted back in the hold of the ship at nightfall. When it rained, which it often did, the prisoners huddled in the gloom of the ship’s hold, wondering when (or if) they would ever be released. The 250 Americans on the Hector were delighted to be leaving, until they realised the British were sending them somewhere even worse.1

After gathering their belongings, the prisoners were called forward by name, handed an allowance of bread and fish, and given a pair of new shoes. They were then ferried by launches to New Passage, close to the centre of Plymouth and not far from where the Mayflower had set sail for New England nearly two hundred years earlier. On the shore to greet them were hundreds more British soldiers, a lavish escort reflecting Plymouth’s military importance, and a crowd of curious locals. (Some of the latter were surprised that the prisoners spoke English.) The Transport Board, the arm of the British government which oversaw the prison system, would not give these Americans even the slightest opportunity to slip through their clutches and into the busy naval yards. Instead, they were mustered again, paired up with their escorts, and ordered to march north. They had a lot of ground to cover before nightfall.2

The Americans were mostly young—in their teens or twenties—and came from across the Union, from New Orleans to New Hampshire and everywhere in between. Several were born outside the United States: in Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, and even Britain. The oldest prisoner, Edward Johnstone, had been born in Darlington in northeast England in 1745; he would turn seventy before his release in 1815. Twenty-two of this first complement of prisoners were Black; all of them told the British they’d been born in the United States save for John Newell and James Lawson, respectively, the cook and the steward of their vessels, who gave their birthplace as ‘Africa’. Most had been captured aboard American privateers, commercial vessels which had been retooled after the declaration of war with Britain to complement the (tiny) US Navy. But dozens of the prisoners had been fighting for the other side when the war broke out. These men had been ‘impressed’ into the Royal Navy, seized and bundled onto British ships to serve His Britannic Majesty.3

The War of 1812 had thrown all of these sailors together, but their diverse backgrounds and pathways to captivity complicated the matter of solidarity. Was every prisoner a loyal American? Now that they’d found their way into the sprawling British prison complex, were they all on the same side? Those questions had already been asked aboard the Hector, and they would emerge repeatedly in the months and years ahead. For now, though, on this damp and grey morning in Plymouth, they would have to wait. At half past ten, the prisoners were told to begin their march northward, through the western reaches of the city and out into the countryside. Any prisoner who stepped out of line would be killed, or so went the threat from the British commander. Buildings gave way to fields and hedgerows, and the pace was unrelenting. The party made one stop around eight miles into the journey, and the prisoners rushed to finish the bread and fish they’d been given in the morning. Then they began the march again, and the hedgerows and fields were replaced by a bleak and treeless moor.4

As the rutted road became steeper, snow appeared on the barren land to each side. For the Americans, the emptiness of the terrain was disconcerting. This was, one later wrote, ‘the Devil’s Land, inhabited by ghosts and sundry imaginary beings. Rabbits cannot live there, and birds fly from it.’ Nearly a century later, when Arthur Conan Doyle wrote about the same ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- List of Figures

- Introduction

- Part I. King Dick at Vienna

- Part II. King Dick at Bordeaux

- Part III. King Dick at Dartmoor

- Part IV. King Dick at Boston

- Acknowledgements

- Notes

- Index

- Copyright