- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

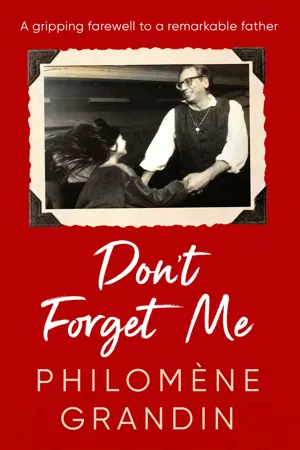

Don't Forget Me

About this book

'A lovely tribute' Joan Baez

'Fascinating' The Dylan Review

Izzy Young was a distinctive figure in the folk music and beatnik world. He set up the Folklore Center in New York’s Greenwich Village, where Patti Smith, Emmylou Harris and Allen Ginsburg performed, and he produced Bob Dylan’s first show in New York in the 1960s. In 1973, Izzy moved to Sweden, where he opened up a similar cultural centre.

In Stockholm, the young Philomène and her father resided in the basement of the folklore centre, living a bohemian life, rich in culture and love. Thirty years later Izzy is fighting dementia.

In a raw and unembellished manner, Philomène depicts the emotional rollercoaster of losing a beloved parent and a larger-than-life personality to an invisible, invincible foe. Interspersed are small moments of joy as the fog briefly parts to allow for a reconnection. Philomene masterfully intertwines the two timelines with a beautifully sparse language that vibrates with emotion. Don’t Forget Me is a deeply personal book, yet the story itself is highly universal.

'Fascinating' The Dylan Review

Izzy Young was a distinctive figure in the folk music and beatnik world. He set up the Folklore Center in New York’s Greenwich Village, where Patti Smith, Emmylou Harris and Allen Ginsburg performed, and he produced Bob Dylan’s first show in New York in the 1960s. In 1973, Izzy moved to Sweden, where he opened up a similar cultural centre.

In Stockholm, the young Philomène and her father resided in the basement of the folklore centre, living a bohemian life, rich in culture and love. Thirty years later Izzy is fighting dementia.

In a raw and unembellished manner, Philomène depicts the emotional rollercoaster of losing a beloved parent and a larger-than-life personality to an invisible, invincible foe. Interspersed are small moments of joy as the fog briefly parts to allow for a reconnection. Philomene masterfully intertwines the two timelines with a beautifully sparse language that vibrates with emotion. Don’t Forget Me is a deeply personal book, yet the story itself is highly universal.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

2016

‘Your dad asked me to call. It’s full of journalists here. It might be a good idea if you come as fast as possible.’

‘Why? What’s wrong?’

‘Bob Dylan got the Nobel Prize.’

I leave my lunch untouched on the kitchen table. A brush of mascara and then I cycle as fast as I can. Ten minutes later I’m pedalling up Wollmar Yxkullsgatan. From a distance I see a small queue forming outside the store. It’s not a store really, more a space where Papa arranges concerts one or two times a week or sits drinking coffee with his friends. I rip off my helmet before I reach the crest of the hill. Park my bike outside the store: peering through the window I see Papa already flanked by two of his neighbours. Guardian angels. ‘Here comes the daughter. Let her through.’ I enter the store feeling embarrassed by the importance I’m given. They explain that they’ve drawn up a list of who goes first and that the journalists are waiting outside until it’s their turn. Papa is sitting on his throne in front of the computer, a tall desk chair upholstered in black leather. It’s actually not a desk chair; it’s a barber’s chair, one of those you can pump up and down with your foot, another present from his friends and acquaintances. On his head he sports a sun hat, even though it’s mid-October. Oblivious to the flashing cameras and the glare of television lights, he has a friendly greeting for everyone who enters. Reporter after reporter is granted an audience. They plant snares, trying to make him say something nasty about Dylan. But he sidesteps all their traps, he jokes, compares their cameras, loudly shouting in American English:

‘Which one of you has the biggest? Which one of you is smartest?’

His broad New York Jewish accent fills the room. I recognize his humour. I pass through to the small kitchenette at the back of the store, search for a glass among the litter of folk-music magazines, compact discs and papers cohabiting the shelf with kitchen utensils. Finally I find one that is not too dirty. I fill it with water from the basin in the toilet. Trying not to breathe through my nose. Like the rest of the store, the walls of this tiny WC are covered with paintings and posters. Above the toilet is a framed note I scrawled as a teenager: ‘Gentlemen are requested to lift the toilet seat when peeing.’ A vintage 1980s pink paper clip is fixed to one corner of the note. The soles of my shoes stick to the floor.

I re-enter the makeshift film studio, pass the overflowing bookshelves and hand Papa the glass. I’m rewarded with a smacking kiss on the cheek.

‘This is my daughter. I’d never survive without her!’

In the middle of all this commotion the landline rings. The Swedish Academy wants Dylan’s number. The woman calling, she might have said that her name was Sara, speaks in a dry, terse tone, like the worst sort of journalist. She wants the phone number and she wants it now. I ask her to call back in five minutes. She refuses to hang up. I throw the receiver down, start riffling through ancient address books and email messages. I scan all the phone numbers Papa has scrawled in thick black felt-tip pen on the wall. I open drawer after drawer in the counter built along one of the walls, the one piece of furniture left over from the days when milk and dairy products were sold here. I find some contact information but it’s full of odd number sequences. Papa is busy with the journalists, angry now that they insist on asking their questions in English:

‘Forty years I’ve been living here, I can speak Swedish!’

Though actually he’s jumping between the two languages at random.

A couple of minutes later the woman from the academy is on the phone again and I still haven’t found what she’s looking for. Papa hears the call and gets irritated at the constant interruptions. He shouts:

‘Tell them to fuck off!’

Once more I put down the phone as I hear him tell his story for the hundredth time:

‘Dylan walked into the store, same as everyone else. He picked up a guitar, started playing and then we became friends. I think it took about thirteen minutes. He wrote two songs for me!’

Papa takes a gulp of water:

‘I was the first one to let him play a big hall. That’s why he trusted me. When I rented Carnegie Hall people said to me: “Izzy! Are you crazy?”’

He mimics their wide eyes and gaping mouths:

‘But I just said, “This kid is the best I’ve ever heard.” And I don’t joke about those things.’

Finally, all the journalists’ questions have been answered. Also, I’ve located the right contact information for Dylan’s manager. I send it in a text message to the woman from the academy. Twenty-four hours later Dylan still hasn’t responded. No one knows if he intends to accept the prize or not. The man is silent. The Swedish Academy tells Dagens Nyheter, Sweden’s major daily, that they were finally able to reach Dylan’s manager. Supposedly he told them that ‘he had no idea if, or when, the artist would acknowledge the prize’. Apparently, Dylan was napping before a concert when the prize was announced and was not to be woken.

Papa, on the other hand, was up at six in the morning for a live interview on Swedish national radio. He managed to set his alarm, dress himself and go downstairs to the street in time to catch the taxi. He can do it, when he needs to.

I’m eating breakfast with the children and turn the radio on. One of the old kind, a box with dials and an antenna. It lives on the windowsill sharing space with kids’ drawings, old newspapers and ripening fruit. Natasha, my daughter, crunches cornflakes and feeds her teddy. I run a hand over her cheek. So soft and round. She’s named after a character I played in a production of War and Peace many years ago. My golden-curled son, Nikolai, taps his phone. Soon he’ll rush out the door on his way to school. He’s grown too big for cuddling. Lasse is grinding coffee beans. When they whirl through the blades it sounds like the kitchen is about to explode. I lean in to the radio to hear Papa’s gravelly voice, just in time to catch the radio host asking:

‘So, Izzy, what do you think about Dylan getting the Nobel Prize?’ He answers without hesitation:

‘He should have got it thirty years ago!’

I sigh with relief. The whole interview could have been a disaster.

An hour later I meet Papa at the store. He stands leaning against the doorpost, waiting for me. He’s calm but eager for a coffee. Arm in arm we walk to our favourite coffee shop on St Paulsgatan. On high bar stools we sit side by side next to the window. Looking out. Watching people passing by. I rub his back and feel the warmth. He’s smaller now. He who used to be the biggest.

1980

I’m six years old and we’re lying in the grass in a nearby park, Mariatorget. As we often do. Papa’s dark-blue suit jacket is spread out under us. He lies on his stomach, writing with tiny letters in his journal. I lean my head on his back and look in my comic book. You can buy them for two kronor each at the store around the corner. They look almost as good as new. The grass tickles my arms and legs.

We lie there like that for an hour, maybe two. Sometimes I run across to the swings or dip my feet in the fountain. Other times I nod off, or Papa does. Then he shakes out his jacket and we walk to the store.

The store. The centre. Papa’s place. There’s always been the store ever since I was a baby. Our second home, Papa’s workspace. He taps on the typewriter, cuts and pastes text and photos into his folk-music newsletter. Page 1, 2, 3, 4. I draw. There are books about folk music. Everywhere. Papa’s library. Ceiling-high bookshelves. The walls covered with photographs and concert posters. Scissors, tape and glue stick. He snips articles from all the Swedish newspapers, and foreign papers when he can get them. He glues them on to blank sheets of paper, scribbles the date and files them in loose-leaf binders. There are binders for folk music, for Dylan, for the war in Cambodia, for the conflict between Israel and Palestine. I make my own magazine, borrow Papa’s pens, sticky with glue, his light box and his rulers.

Papa often props the door open with the Golden Boot he won, a prize awarded by Dagens Nyheter. I don’t really know why he got it. Something to do with folk music probably, something about the store. It looks like a beat-up Charlie Chaplin boot, unglued at the sole with nails sticking up. It’s made of gold; even the shoelaces are golden. I like to carry it around. It weighs several kilos.

People come in sometimes. Usually older men. They ask about some record or book, or they ask if it’s true that Papa knows Bob Dylan. Papa sighs. He doesn’t have much for sale, a few records, an odd instrument, but they should at least buy his newsletter. It only costs five kronor.

‘You should be supporting me!’

If they don’t buy anything, he throws them out and we watch as they scuttle down the street in shock.

Three huge storefront windows look out on to the pavement and the enormous tree on the corner that gives us shade in the summer.

2016

I’m sitting on a chair in a stranger’s kitchen. I put my make-up on attempting to look natural, just a shade prettier than usual. The man making the documentary about Papa wants the apartment he’s rented to seem as if it’s mine. I try to look relaxed, sitting by the kitchen window with a cup of coffee. I pull my legs up under me, trying to look bohemian in my black dress.

The film-maker sits perched by the camera a couple of metres away. He talks unceasingly, wants to film me backlit. I ask if I won’t just become a silhouette then. He answers in perfect British English that his super-expensive camera will fix it. Will fix everything. He presses the record button:

‘So, tell me about your father’s store in New York.’

I don’t know all the names of everyone who played in Papa’s store sixty years ago. Also, my English deteriorates when I get nervous. I’m tracing the rim of the coffee cup with my finger, the palms of my hands are all sweaty.

The film-maker isn’t satisfied with my answers. He starts dictating what I should say, spells things out and wants me to memorize lines. I sit straight up, trying to rattle off names as if it were common knowledge that they played there:

‘Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell, Bob Dylan, Emmylou Harris, Pete Seeger, Mississippi John Hurt, Patti Smith and… um… loads of other musicians and poets. They all used to perform at the Folklore Center.’

I notice how the words come out garbled.

‘It was like a… mecca for folk music in Greenwich Village.’

Two hours later I’ve repeated a litany of facts on demand. I related how Papa was born in 1928 in the Bronx and how his parents emigrated to the USA from Poland. With feigned enthusiasm I told the story of how Papa opened his store in New York at the end of the fifties. I described Bob Dylan, sitting at Papa’s old typewriter, tapping out lyrics to his songs.

I clear my throat:

‘But one day Papa had a visit from some Swedish folk musicians, Björn Ståbi and Bror Hjorth. They became friends. He developed an infatuation for Swedish folk music. It was that love, along with his hatred of the war in Vietnam, that made my parents move to Sweden in 1973. I was born a year later.’

The film-maker shuffles his notes. I believe that my parents’ break-up, shortly after my birth, is not something he would be interested in so I don’t mention it. Neither do I describe the way I lived one life with my mother and an entirely different one with my father.

We’re finally done. I’m released out on to Mariatorget. I wipe the palms of my hands on my dress, fill my lungs with fresh air and look up at an open blue sky.

1981

Stockholm is moving slower; the summer holidays are here. Papa and I are sitting on a bench in Björns Trädgård, a city park paved with warm, grey asphalt. We sit opposite one another, two benches with a table in between. Papa has bought a half-litre block of ice cream. Nougat and vanilla. It’s cheaper and perhaps even tastier than ice creams on sticks. He’s brought with him two teaspoons and a knife from the cutlery drawer at home. All badly cleaned. He takes them now from his jacket pocket. Measuring the block, he meticulously performs the holy tradition of dividing the ice cream equally.

Papa, in deep concentration, saws through the ice cream. The carton frays at the cut edges. Once divided, he sets the two pieces next to each other so that we can see if he’s cut fairly. He’s almost always proud of the result. He’s the phenomenal son of a baker ‘from the Bronx’ who learned as a child how to cut loaves of bread in precise and equal slices. The baker’s son who on early mornings, in a New York bakery misty with flour, tossed hot loaves, fresh from the oven, to his little brother.

The ice cream is soft. It took a few minutes to walk from the grocery store to the park. Only Papa and I are here, and a few stubborn pigeons. Stockholm’s other residents have probably left town for summer cottages.

We eat in reverent silence. Scrape our silver spoons against the smooth interior of the carton. Nothing should be wasted. Ice cream oozes from the side of the carton. Sticky. Delicious. Always a drop on Papa’s shirt or trousers.

This is our day’s adventure, the high point, what the loose change in Papa’s pockets allows. On a day that we can splurge we might buy a lottery ticket at the food store. The one with little flaps that you bend up to see if you have the right numbers. We don’t win very often, but it’s always exciting. If we do win, five kronor perhaps, the day will turn out completely differently. We can afford to buy something more, something different.

Even though we don’t own a car we sometimes buy a parking ticket. You buy them from a machine and they cost next to nothing. Papa lifts me up so that I can press a coin into the slot. My stomach tingles as it drops and the machine spits out a printed ticket. On the ticket you can read the time, the date and how long we’re able to occupy a space on the street. That’s all. A pleasant feeling, the excitement of getting a piece of paper from a machine. I think we’re stealing a parking space from someone.

I go to the swings. Swing to and fro, to and fro, long hair flying, my stomach fluttering. Sticky ice-cream fingers grip iron chains. In the corner of my eye a bird, a cloud, Papa reading the newspaper. I can sit here for hours.

On the way home a seagull poops right on the top of my head. I rub the buildings with my shoulder, walking tight behind Papa. Will he help me to wash it out when we get home? Maybe we’ll rinse my hair in the kitchen sink; maybe we’ll just wipe it off with a paper towel.

2016

It’s November, early morning, and I’ve just packed Natasha off to daycare. The first freeze laid a fragile, overnight crust on all the puddles. I walk with quick steps across the pavements in Södermalm when Papa phones. His voice sounds happy; at the same time he’s almost out of breath. He reads a letter out loud in broken Swedish, stuttering through each syllable.

‘The Nobel Foundation… req...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- 1. 2016

- 2. 1980

- 3. 2016

- 4. 1981

- 5. 2016

- 6. 1981

- 7. 2016

- 8. 2016

- 9. 1981

- 10. 2016

- 11. 2010

- 12. 1982

- 13. 2011

- 14. 1982

- 15. 2016

- 16. 2002

- 17. 1982

- 18. 2016

- 19. 1982

- 20. 2016

- 21. 1983

- 22. 2010

- 23. 1983

- 24. 2016

- 25. 1984

- 26. 2016

- 27. 2016

- 28. 1984

- 29. 2016

- 30. 2003

- 31. 1985

- 32. 2016

- 33. 2011

- 34. 2016

- 35. 1985

- 36. 2016

- 37. 2016

- 38. 1987

- 39. 2004

- 40. 2016

- 41. 2012

- 42. 1987

- 43. 2016

- 44. 1987

- 45. 2017

- 46. 1987

- 47. 2017

- 48. 1988

- 49. 2018

- 50. 2018

- 51. 2018

- 52. 1989

- 53. 2018

- 54. 1989

- 55. 2018

- 56. 2018

- 57. 2018

- 58. 1991

- 59. 2018

- 60. 2018

- 61. 2018

- 62. 2018

- 63. 2018

- 64. 2018

- 65. 2018

- 66. 1993

- 67. 2018

- 68. 2018

- 69. 1996

- 70. 2012

- 71. 2018

- 72. 2018

- 73. 2018

- 74. 2018

- 75. 2018

- 76. 2018

- 77. 2019

- 78. 2019

- 79. 2019

- 80. 2019

- 81. 2019

- 82. 2019

- 83. 2019

- 84. 2019

- 85. 2019

- 86. 2019

- 87. 2019

- 88. 2019

- 89. 2019

- 90. Thank You

- 91. 2018

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Don't Forget Me by Philomene Grandin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.