![]()

1

Managing Globalization and Regional Integration Post-COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic tested the resilience of health and economic systems worldwide.

Since it was first reported in December 2019, the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) infected more than 100 million, with more than 2.2 million lives lost (Figure 1.1). Across regions, Europe and North America were hardest hit. Asia initially had the highest number of confirmed cases but was overtaken by other regions in March 2020.1 As of 4 February 2021, Asia reported 15.8 million confirmed cases.

Figure 1.1: Global COVID-19 Confirmed Cases, By Region (million)

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease, PRC = People’s Republic of China, SARS = severe acute respiratory syndrome, UK = United Kingdom, WHO = World Health Organization.

Source: World Health Organization statistics downloaded using CEIC.

The virus spread rapidly across the globe, shutting down or affecting almost all spheres of human activity—from travel to education, business, and work, along with social and family life. The pandemic also tested national health systems around the world, straining even the most advanced hospital systems in France, Italy, Germany, and the United States (US), among others.

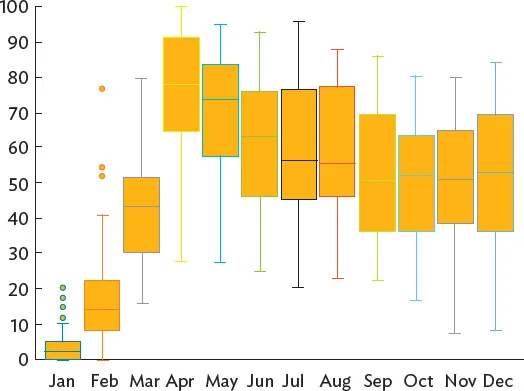

The devastating impact of COVID-19 forced many regional, national, and subnational authorities to implement stringent border controls, lockdowns, and community quarantines to contain the spread of the virus. In Asia, the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Stringency Index for government response to the pandemic fluctuated from around 20 index points in February, to a high of 76 in April, then falling to 50 index points in October and November before rising in mid-December to 53 index points (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2: Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Stringency Index—Asia, 2020

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease.

Notes: The Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Stringency Index is a composite indicator, with a range of 0 to 100 (most restrictive), that captures policy decisions on (i) school closings, (ii) workplace closings, (iii) cancellation of public events, (iv) restrictions on gathering size, (v) public transport closures, (vi) home confinement orders, (vii) restrictions on internal movement, (viii) international travel controls, and (ix) public information on COVID-19. Data as of 21 December 2020. The middle line of the box represents the median. The upper (bottom) line of the box represents the median of the upper (bottom) half. The vertical lines extend from the ends of the box to the minimum and maximum values.

Source: Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford. Coronavirus Government Response Tracker. https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker (accessed December 2020).

Unsurprisingly, the pandemic plunged the world into its deepest recession since the end of the Second World War. In 2020, the global economy was expected to contract by 3.5%, 6.3 percentage points lower than the 2.8% growth in 2019. The International Labour Organization estimated that about 73.7% of workers globally were affected by mobility restrictions as of May 2020, and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimated 242 million job losses and foregone wage income of $1.8 trillion (Park et al. 2020).

The pandemic further tested existing relationships among nations around the world.

Before COVID-19, globalization in trade, investment, finance, and migration was facing headwinds, spurred by geopolitical tensions over trade between the US and the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the United Kingdom (UK) “Brexit” vote, along with rising polarization and social inequality. Globalization had been viewed by some countries as a source of insecurity—opening local economies to unwanted migrants, creating unfair competition, contributing to rising inequality, and destabilizing peace, order, and culture. Skeptics said that globalization was also partly responsible for financial cycles that could destabilize capital flows and threaten macroeconomic stability. These negative public perceptions were reinforced by stagnating wages and limited growth in job opportunities.

Thus, it was unsurprising to see that—as global trade and health systems teetered under the COVID-19 strain—the tendency to prioritize self-interest strengthened the questioning of globalization itself. Will it wither and fall? Will it be replaced by stronger regional arrangements? Or will it drift toward a stronger emphasis on sovereignty and nationhood?

The pandemic severely disrupted Asia’s cross-border flows and activities.

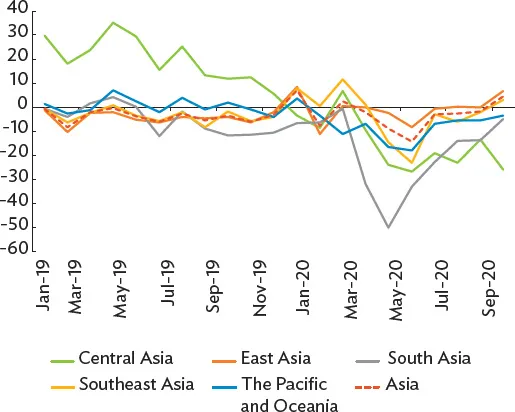

Border closures, lockdowns, quarantines, and other means to control the virus spread disrupted supply chains and weakened demand, resulting in an overall decline in global trade. Intraregional trade within Asia declined during the first half of 2020, with Central and South Asia subregions reporting large contractions in intraregional trade (Figure 1.3). In South Asia, intraregional trade fell sharply in April as economies entered strict lockdowns. The gradual recovery of global and intraregional trade in the second half of the year reflected the measured reopening of economies and weak demand.

Figure 1.3: Intraregional Trade Value Growth—Asia (%, y-o-y)

y-o-y = year on year.

Source: ADB staff calculations using data from International Monetary Fund. Direction of Trade Statistics. http://data.imf.org/DOT (accessed December 2020).

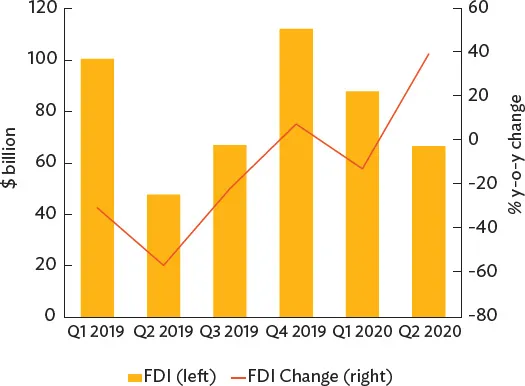

Cross-border investments also contracted in 2020 as multinational enterprises postponed or canceled their planned or ongoing investment projects amid the uncertain prospects of economic recovery, duration of the pandemic, and earnings. Foreign direct investments (FDI) to selected Asian economies declined by over 10% year-on-year (y-o-y) in the first quarter of 2020, with Bangladesh, the PRC, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, and Mongolia dropping by more than 20% (Figure 1.4). The decline in Asia’s FDI reflected the region’s vulnerability to supply chain disruptions and growing uncertainties on business conditions. Although FDI inflows captured through balance of payments data stalled, firm-level cross-border investment data in the second quarter of 2020 showed early signs of recovery through higher mergers and acquisitions.

Figure 1.4: Foreign Direct Investments—Selected Economies

FDI = foreign direct investment, y-o-y = year on year.

Note: Sample includes Bangladesh; Cambodia; Hong Kong, China; India; Indonesia; Kazakhstan; Mongolia; Nepal; the People’s Republic of China; the Philippines; the Republic of Korea; Taipei,China; and Thailand.

Source: ADB calculations using national source data accessed through CEIC.

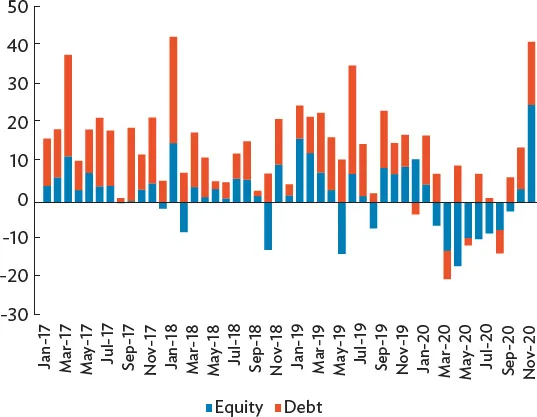

Foreign portfolio financial flows reversed in March 2020 as global investor sentiment deteriorated, uncertainties mounted, and liquidity conditions tightened at the height of the COVID-19 outbreak. Nonresident portfolio outflows to the region amounted to $20 billion, mostly equity outflows (Figure 1.5). This coincided with a steep fall in equity prices in March. But monetary, financial, and fiscal support measures were swiftly implemented globally, resulting to an easing of financial conditions and a recovery of asset prices by June 2020, leading to the resumption of nonresident portfolio debt inflows by June 2020. Yet, for some economies in the region, equity prices in the second half of 2020 (H2 2020) were nowhere near their values at the start of year, and the risks of tightening liquidity conditions and corporate insolvencies loomed large toward the end of the year.

Figure 1.5: Nonresident Portfolio Flows—Emerging Asia ($ billion)

Source: Institute of International Finance. Capital Flows Tracker. https://www.iif.com/Research/Capital-Flows-and-Debt/Capital-Flows-Tracker (accessed December 2020).

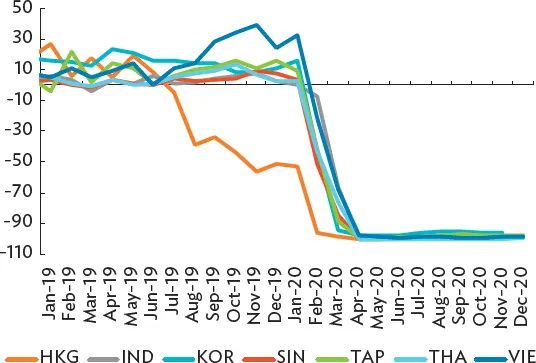

International travel ground to a halt in the second quarter of 2020 as 217 destinations, including those in Asia, implemented total or partial border closures, flight suspensions, travel restrictions, and other measures to contain the spread of COVID-19 (Figure 1.6). In Asia, tourist and visitor arrivals in April completely stopped in India, Maldives, Singapore, Sri Lanka, and Thailand, while arrivals fell to a trickle in Cambodia; Hong Kong, China; the Republic of Korea; Taipei,China; and Viet Nam. By H2 2020, travel restrictions were gradually eased. As of 1 November 2020, 152 destinations had eased COVID-19-related travel restrictions, while 59 destinations kept their borders completely closed to international tourism. In Asia, 27 destinations maintained total border closures, while 22 destinations, including 5 small island developing countries, had partial border closures or specific travel restrictions.

Figure 1.6: Growth in Tourist and Visitor Arrivals—Selected Economies (%, y-o-y)

HKG = Hong Kong, China; IND = India; KOR = Republic of Korea; SIN = Singapore; TAP = Taipei,China; THA = Thailand; VIE = Viet Nam; y-o-y = year on year.

Source: ADB calculations using data from Haver Analytics.

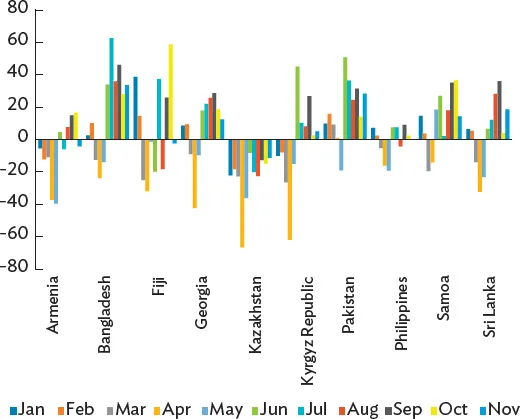

Remittance flows to Asia also plunged amid the pandemic, with the drop most severe during the strict lockdown phase in April 2020 (Figure 1.7). For the first half of 2020 (H1 2020), remittances fell by 30% in Kazakhstan, 13% in the Kyrgyz Republic, 17% in Armenia, and 9% in Sri Lanka. While some migrant workers increased their remittances to families in extremely difficult situations back home, the prevailing weak economic situation in host economies also contributed to the sharp decline in remittance inflows. In some economies, this reversed in June as lockdowns began to be lifted in destinations that allowed migrants to remit their accumulated money from previous months—usually over the counter or through money transfers. Some governments in the region also introduced policies to incentivize transfers by reducing compliance checks, restrictions, and transaction fees; as well as undertaking an aggressive promotion campaign to migrants to prop up remittances.

Figure 1.7: Remittances to Selected Countries in Asia, January–November 2020 (% change)

Note: Numbers refer to the year-to-date percent changes (base year 2019) in remittance inflows to selected Asian economies.

Source: ADB calculations using data from the central banks of respective economies (accessed January 2021).

Restraints on cross-border activities and weak demand weakened the region’s economic prospects in 2020, with developing Asia likely to contract in 2020 for the first time in 6 decades.

Most economies contracted in H1 2020 due to the strict containment measures that disrupted supply and slowed consumption. The US economy contracted by 4.3% and the euro area by 9.0%. Most economies in Asia also contracted during the period. Based on national data released as of December 2020, the PRC economy shrunk by 1.6%, Indonesia by 1.3%, the Republic of Korea by 0.7%, and the Philippines by 9.3%.

Prospects for a swift and robust recovery waned in H2 2020 as the number of COVID-19 cases continued to rise. Concerns over recurrent “waves” of infections, particularly during the winter season in the northern hemisphere, and reinstating localized lockdowns while slowly reviving economies weighed down growth outlook. Moreover, new virus strain in Europe raised fears of sustained high infection rates in the coming months. Nonetheless, there were signs of an upturn in business and consumer confidence and cross-border transactions, including trade and investment, although still lower than pre-pandemic levels. More importantly, news on the high efficacy of candidate vaccines supported the prospects of sustained economic recovery in 2021.

ADB’s Asian Development Outlook Supplement December 2020 projec...