![]()

Chapter 1

In and Out OF THE STUDIO :

Early Professionals and Amateurs

Lady Clementina Hawarden, Clementina Maude with her arms raised, c.1862

“Woman is born free and lives equal to man in her rights,” wrote the political activist Olympe de Gouges in Declaration of the Rights of Woman (1791). Her text would pave the way for what by the early 1900s would become known as “feminism” (and would later see de Gouges executed for treason). Around the world, legislation, collective action and philosophical texts were beginning to shift ideas of freedom and equality in both directions – in 1734, the introduction of Swedish Civil Code protected married women’s property rights; in 1792 a bill granted the vote to female heads of household in Sierra Leone; while from 1777 US laws began to take it away from some women.[1] By the time photography was introduced to the world in Paris in 1839, campaigns for women’s rights had gained serious momentum.

This swell of activity was due in no small part to the emergence around 1830 of the official abolitionist movement to end slavery. Women fighting for reform saw that freedom and equality should be applied to gender as well as race, and for many years the causes overlapped. As the struggle for women’s rights grew, however, so it became more divided. In many parts of the world, industrialization had transformed the nature of women’s work. In doing so, it had also widened the gap between the social classes, who experienced oppression in different ways. The concerns of the laborer or factory worker, who unionized to protect herself from workplace exploitation, were unlike those of her middle- and upper-class contemporaries, who were fighting for better education and the right to own property, or who were railing against enforced lives of leisure (Polish revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg, for example, went so far as to declare the female bourgeoisie to be parasites on society).[2] These class- and gender-based concerns were amplified for women of color, especially after the dramatic divergence of the abolitionist and women’s movements around the passing of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1869, when African American men were granted the right to vote, but women were not.[3]

It was in this transformative context of rights reform that photography became ingrained in cultural life. Women began to use their changed socio-economic positions to take up new vocations, and, of all the fields in photography, it was studio portraiture that presented more professional opportunities than any other.

Zaida Ben-Yusuf, The Odor of Pomegranates, 1899

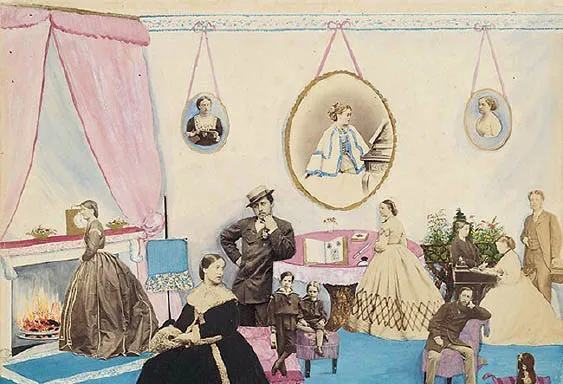

Lady Mary Georgiana Caroline Filmer, Lady Filmer in her Drawing Room, 1863–8

Annapurna Dutta, Self-Portrait, c.1920s

A DEMOCRATIC MEDIUM?

The introduction of photography incited a global mania for Daguerreotype portraits and from that the lower-priced cartes de visite. Within just a few years of the medium’s invention, capturing one’s “likeness” – or, more poignantly, crafting one’s identity through the photographic image – went from being the preserve of the upper classes to something that people from all walks of life could afford.[4]

On the other side of the camera, however, things were not so egalitarian. Around the world, studios were opening in great numbers, but only a handful had women at the helm. Photography historian Naomi Rosenblum notes that of the 750 studios that opened in England and continental Europe between 1841 and 1855, just 22 were run by women.[5] Figures from the US reflect how, later, the number of professional women photographers grew exponentially: from 271 in 1880 to 4,900 in 1910, representing 15 percent of the field.[6] Yet these statistics tell only part of the story. As photographer and researcher Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe has explained, the US census listed white women’s occupations only from 1870 (figures that were confused anyway because of the American Civil War) and Black women’s only from 1890.[7] That year, she states, of 2,201 women photographers recorded, 6 were Black women.[8] By 1920, there were more than 100.[9]

In part, this growth can be attributed to the fact that photography was becoming more accessible, in terms of technology (which was becoming more user-friendly and less labor-intensive) and training (one could be self-taught, or learn via a short apprenticeship), as well as economics. In 1890, $10 – the equivalent of about two weeks’ wages for factory workers – could purchase the equipment necessary to set up a portrait business, which some did from their homes.[10] For women without the means to set up shop themselves, studios offered many other administrative and technical roles, including retouching portraits, preparing materials for printing, or working as a “lady operator” for clients who preferred to be photographed by a woman.

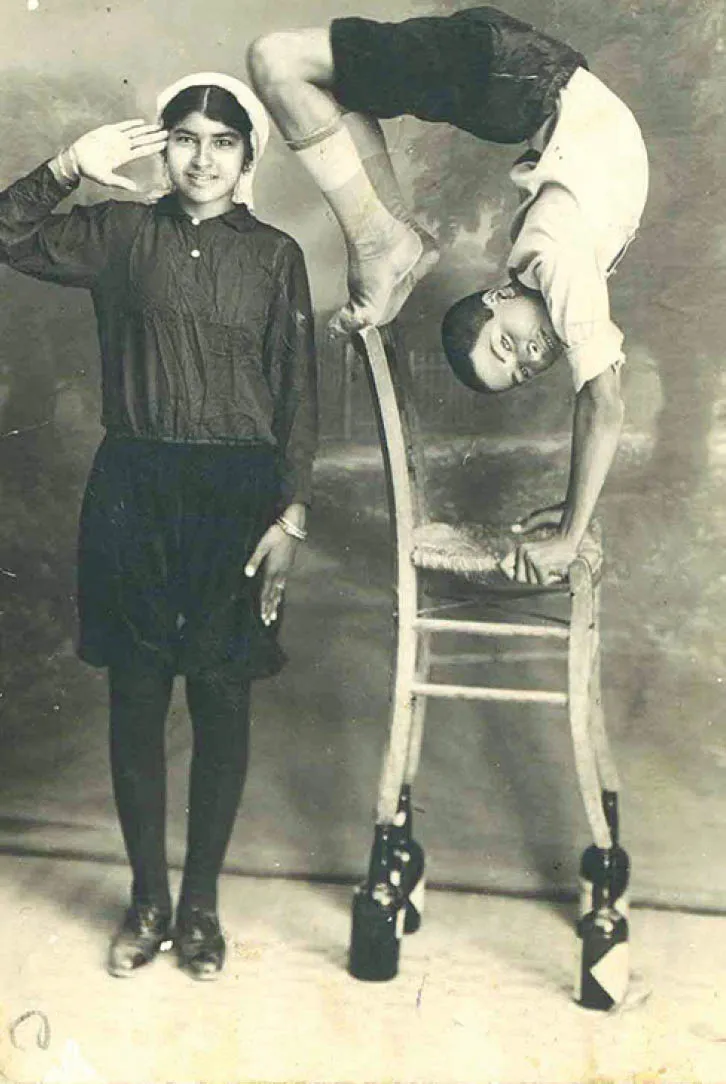

Alongside access to training, equipment and materials, there was another major factor determining women’s entry into professional photography: notions of social propriety. For this reason, historians mapping out women’s early achievements in the field have to not only identify global “firsts,” which tend to privilege those active in Western contexts, but also account for the local attitudes that determined women’s ability to work. Only then can we understand what it meant for, say, Bolette Berg and Marie Høeg (pages 28–9) to be working in late 19th-century Norway compared to Annapurna Dutta (page 24) and Karimeh Abbud (page 26) in early 20th- century India and Palestine, or to Yamazawa Eiko (page 25) in 1930s Japan, or again to Felicia Abban in 1950s Ghana, who established her studio when the country was on the cusp of independence.[11]

Yamazawa Eiko, Hasegawa Shigure, 1934

Karimeh Abbud, Acrobat [children in a Jerusalem orphanage], 1921

The fact that there were many contexts in which it was not “proper” for women to have their name above the door means that when it comes to understanding their contribution, back-of-house roles should be taken seriously, too. This is as true of Shima Ryū (right), active in 1860s Japan and believed to be among the country’s first female photographers,[12] as it is of Ndèye Teinde Dieng in 1960s Senegal, who revealed in the 2000s that she was jointly responsible for the expert printing of the photographs that were distributed under her husband’s name.[13]

ARTISTS AND AMATEURS

Restrictive notions of propriety also mean that an examination of professionals working in practising studios is not sufficient to gauge women’s foothold in photography: we must also look at the work of non-professionals and artists.[14] Some upper-class women in Victorian England, such as Lady Clementina Hawarden (page 22) for example, used the time and resources at their disposal to explore photography’s artistic potential. Although they were allowed to exhibit and were active in camera clubs, it was still deemed inappropriate for them to sell their (often highly accomplished) work. Around the same time, Lady Filmer (page 23) and others were upping the creative ante by combining cut-out photographic portraits with watercolor scenes and motifs. These works, being largely made for private consumption, have evaded serious scholarship until recently. They are nonetheless valuable documents alive with insight into social mores of the time and the (often juicy) dynamics between the individuals pictured.[15]

For those with more slender means than these Ladies- with-a-capital-L, Kodak’s introduction of a roll-film camera in 1888 put photography within reach. Advertised with the catchy slogan “you press the button, we do the rest,” their savvy promotional strategy played on two dominant female archetypes; the “Kodak Girl” exploring the world independently, her portable camera in tow, and the mother keen to capture her children’s precious moments. This approach was a huge success: by 1900, women made up 30 percent of amateur photographers.[16]

Shima Ryū, Portrait of Shima Kakoku [Ryū’s husband], 1864

Although these early cameras had an enormously positive effect in normalizing the idea of women as photographers, they received criticism from international groups of artist- photographers known as the Pictorialists, who saw the popularization of photography as a threat. Dedicated to establishing the medium’s status as fi...