eBook - ePub

The Cabinet-Maker's Guide to the Entire Construction of Cabinet-Work - Including Nemeering, Marqueterie, Buhl-Work, Mosaic, Inlaying, and the Working and Polishing of Ivory

With Instructions for Dyeing Veneers, Trade Recipes, Descriptive List of Cabinet Woods, Etc.

- 188 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Cabinet-Maker's Guide to the Entire Construction of Cabinet-Work - Including Nemeering, Marqueterie, Buhl-Work, Mosaic, Inlaying, and the Working and Polishing of Ivory

With Instructions for Dyeing Veneers, Trade Recipes, Descriptive List of Cabinet Woods, Etc.

About this book

Written to supply a want is a phrase now become so hackneyed, that it is only repeated here because no other words mould so well express the purpose of the writer-which is, to place before the trade a book of instruction on Cabinet-making by a London Cabinet-maker. From the fact of the London trade being divided and sub-divided into so many branches-wardrobe makers, pianoforte-case makers, photographic ap- paratus makers, dining-table makers, telegraphic- case makers, sideboard makers, glass-showcase makers, chiffonier makers, looking-glass-frame- makers, mathematical-case makers, dressing-case makers, toilet-table makers, chest-of-drawers makers, etc., etc.-and each one of these branches taking apprentices, it follows as a natural consequence that there are many workmen who are thoroughly efficient only in the branch in which they have been specially trained. It mill frequently happen, from slackness in a particular branch of trade, or from a other causea, that a workman is compelled to turn his hand to another branch, and he then finds that he must place himself under an obligation to others for instruction. By all such workmen this little book will be found of value, as well as by apprentices and country work- men unaccustomed to many of the branches of the trade treated of in these pages amateurs, also, who take delight in the art will find the book of great service and lastly, it is hoped it may prove useful as a work of reference to the trade in general. The information given is based on an experience of twenty-five years as a general Cabinet-maker, and can be relied upon. All necessary instructions for veneering and inlaying in fancy woods, for both flat and shaped surfaces, will be found here and the process of dyeing veneers throughout their entire thickness, so little known to the trade, is also fully treated of, as well as the working and staining of ivory, marqueterie, buhl-work, etc., and the con- struction of various kinds of dining-tables. Many valuable recipes are also given, and much information of a miscellaneous character, as will be seen from a glance through the following Contents.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Cabinet-Maker's Guide to the Entire Construction of Cabinet-Work - Including Nemeering, Marqueterie, Buhl-Work, Mosaic, Inlaying, and the Working and Polishing of Ivory by Richard Bitmead in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Construction & Architectural Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THE

CABINET-MAKER’S GUIDE.

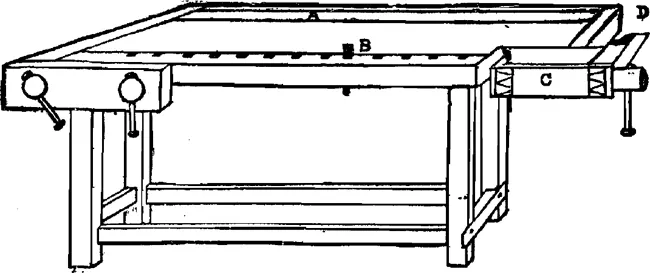

The Work-bench.

ONE of the most essential things for the production of good work is the work-bench; but employers in very many shops trouble themselves little about this, the workman being generally furnished with such a bench as may be found in every little country shop, constructed of four legs framed to a stout top, and fitted with a single or double screw. Now, if the top of the bench should be at all uneven, the work which is planed-up on it will be out of truth; or if the bench should not stand level, one side being higher than the other, all saw-cuts, mortising, dovetailing, &c., will be badly done. The importance, therefore, of keeping the top of the bench planed true and level will be easily seen.

The German bench is the best for a cabinet-maker for all kinds of work. In Germany, the work-bench has had more consideration bestowed upon it than it has in our country; and the result is a bench far surpassing ours, at which the workman can quickly and firmly secure his work in any position, either for sawing or planing, and consequently can do more, less time being occupied in securing the work.

The writer of this Guide has found that with a German bench (Fig. 1) he has been able to earn two or three shillings per week more at some kinds of work than he could have done at an ordinary English bench; and even on common work there is an advantage.

Fig. 1.—GERMAN WORK-BENCH.

The details of the arrangement of the German bench are as follows:—A represents a trough or box, to hold tools not in use; this will be found very useful, as it prevents tools falling off the bench. B, iron stops, with a spring at the side, to hold work, which can be shifted to the holes extending to the head of the bench, so as to hold work of any length. C, the German screw, which consists of a square frame with slips to guide, and screwed underneath one nearest the side marked D, and the other close to the joint of the sliding part near the screw.

The screw at the end is tapped into the clamp D, which is bolted on to the end of the top. The screw is made to fit easy in the frame, with a wedge underneath, the same as the other screws, so as to draw it back. The screw should also be made with a pin at the end, and fitted into the thick piece which carries the iron stop, as it will make it more secure, as well as take the strain when screwed up.

Having fully described the best sort of bench, we will now enter into the different kinds of work to be done on it.

Dovetailing.

There is scarcely any part of the cabinet trade which so plainly shows whether the workman is a good hand or not, as the way in which he dovetails his work. This especially applies to young workmen; for they, above all, must learn accuracy in cutting and joining, and acquire the power of using the saw efficiently, so that the work, when cut by it, should at once join properly, without being hacked or chiselled about, by which both time and patience are wasted, and bad work ensues. It is desirable that a cabinet-maker should work quickly; but it is far more important that he should work well, and that he should join his materials with firmness and accuracy.

It is most important that saws of all kinds should have sufficient “set” to enable them to work with freedom; for it is impossible to turn out good work with a saw without “set,” either in the cutting of dovetails or tenons, as it will be sure to run out and spoil the work, as well as the saw, which, being forced through the work in an unfair manner, will tend to buckle the blade, and to render it useless for good work.

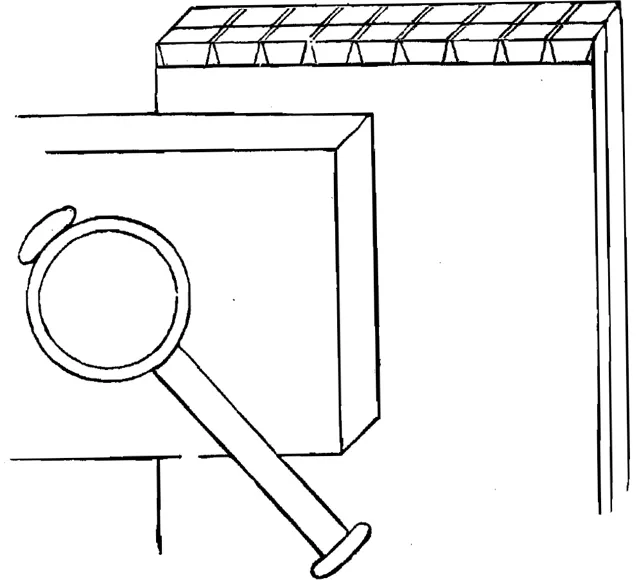

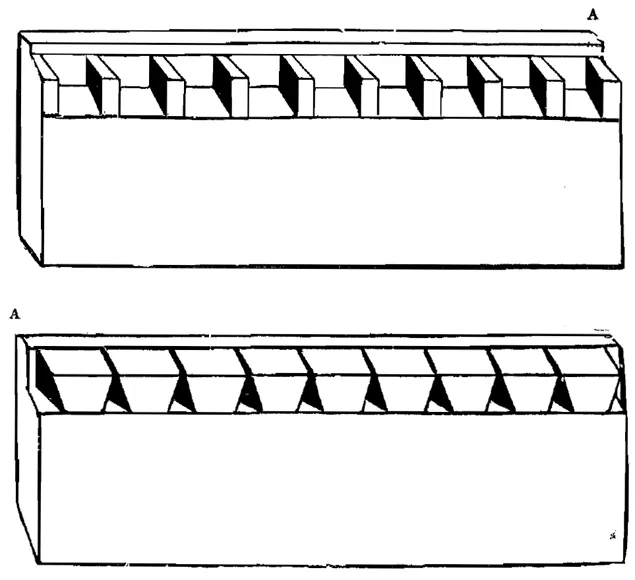

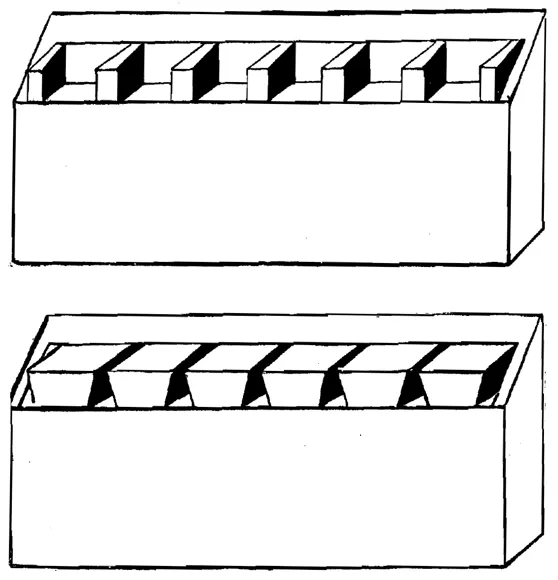

Common Dovetailing.—We will first treat of common dovetailing, in which the pins pass right through. This is the strongest and the quickest done, and consequently the cheapest, less time being required. After the stuff is planed-up quite true, and to a thickness, the first thing required is a shooting-board (which will be found useful for jointing) made of common deal, or any other wood, about four feet long by six or seven inches wide, and of inch stuff, with a piece about two or three inches wide firmly glued and screwed across one end, and set perfectly square from the edge on the side next to the plane, so as to form a stop for the work; the plane to be laid on its right side, so as to plane the edge of the work when laid on the board, and the board to be fitted on the bench, so that when the work is planed it should be perfectly square. Now set the cutting-gauge to the exact thickness of the stuff, and gauge from both sides, then place the front and back together in the screw, and cut the dovetails, as in Fig. 2.

There is a greater advantage in cutting two or more together than there is if the pins are cut first, and the dovetails marked-off and cut separately. Each corner should be marked or numbered, otherwise there will be a mistake when the work is put together. Dovetails should not be cut broad in the front and very narrow at the back, as this weakens the joint, but should be only slightly tapered; these are the best and strongest, and look well.

Fig. 2.—DOVETAILING.

Having cut the dovetails, the next thing is to mark them off, which is done by placing a corner as you intend it to come when finished; then insert the point of the dovetail saw into the saw-cut, and draw it towards you. Great care should be taken not to let the parts slip.

Fig. 3.—LAP DOVETAILING.

For fine dovetailed work in very thin wood, some chop out the dovetails first, and just damp the part for the pins on the end, and then use a pounce-bag for marking. When all are marked off, then cut the pins. Care should be taken to cut a shade outside the marks, so as to let them fit moderately tight. If cut on the marks, the work will be spoilt.

Lap-dovetailing.—Lap-dovetailing is used for drawer-fronts and carcase work. The method is similar to the common dovetailing previously described. In this plan the dovetail is shown on the one side only, a ledge being left at the end of the front, so that the dovetails of the side do not penetrate quite through, as Fig. 3 will explain.

Figs. 4, 5.—SECRET LAP DOVETAILING.

Secret Lap Dovetailing is used for a variety of work, such as cases for instruments, desks, &c. In this system the pins of the front (Fig. 4) are shortened, and the recesses which are to receive them (Fig. 5) are not cut through; and, when joined together, only the ledge is visible on the return side.

Figs. 6, 7.—MITRE DOVETAILING.

First rabbet out the front and back, as in Fig. 4; then cut the pins and mark them off with a marking-awl on the end (Fig. 5), and cut the dovetails inside the marks, so that the pins will fit. The corners marked A will come together when glued up, and when dry are usually rounded to the joint.

Secret or Mitre Dovetailing.—In this plan the dovetails are concealed, and only the mitre at the edges is shown. The manner in which this joint is effected will be understood from Figs. 6 and 7. Mitre dovetailing is applied to the same description of work as mentioned in the preceding section, and is particularly useful where the face of the work forms a salient angle, that is, one which is seen from the outside.

The first thing to be done after squaring up is to gauge on the inside only the thickness of the stuff; then gauge for the rabbet on the ends of each piece, the same as Fig. 4. After the rabbets are made, dovetail together; and when that is completed, take a sharp rabbet-plane, and make the ledges into a mitre; it is then ready to glue together.

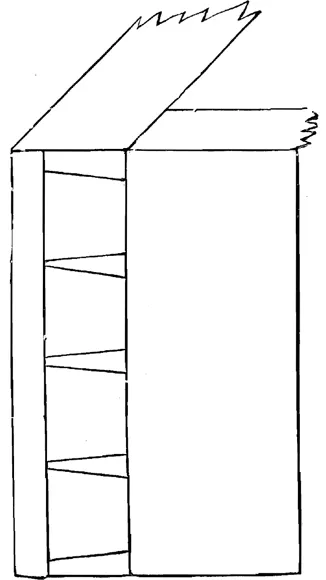

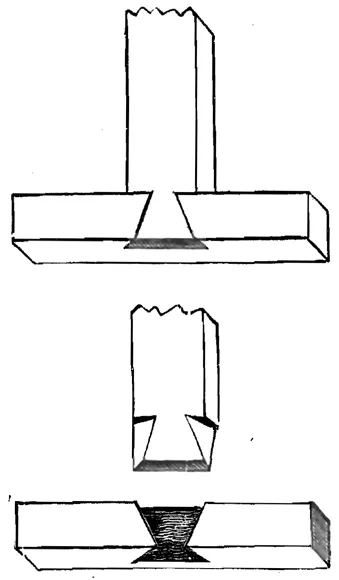

The Double Dovetail is seldom brought into practical use for cabinet work, as it is not much known; but it would be found to be of use in a number of cases, instead of the mortise and tenon. Fig 8 represents it finished, Fig. 9 as taken asunder. The socket in Fig. 9 is inverted, for the better display of its form, and so that its construction may be more easily seen.

The socket is made thus: upon the entering-side a gauge-draught is run at three-fourths the depth, and upon the outside, opposite, at one-fourth, which determines the bottom of the socket; then the full width of the dovetail-pin is marked off upon both sides at the bottom of the gauge-marks, and a bevel set so as to narrow it to the surface in dovetail form on each side; then, from the marks on each side, make a mark across the surface; then cut the sides and chip out the socket, the bottom of which is a parallelogram. The same measures are then taken upon the dovetail-pin, and cut outside the marks.

Figs. 8, 9.—DOUBLE DOVETAILING.

The principal advantages of the double dovetail are these: first, it can be fitted much more nicely and expeditiously than the mortise and tenon; second, the dovetail-pin is strongest at the neck, where most strength is required; third, against a direct pull it acts as a dovetail; and fourth, though this is of little consequence, it can be made and shown as a puzzle. When neatly done, it seems almost impossible to put it together or take it apart. It should be made with a light and dark wood, and glued together; if put together dry, it will be easily taken apart, and the secret discovered.

Mortise and Tenoning.

We will start with a door for a wardrobe or a sideboard. Having determined the thickness of the stuff to be used, select a mortise chisel about one-third of the thickness, and see that it has a long bevel and is sharp. Before commencing, be provided with two parallel pieces of wood, about two inches wide by fifteen long and three-quarters thick. These are called winding-sticks, and should be placed across each stile and rail, one at either end on the faced side. Look down these winding-sticks, and it will at once be seen if the work is in winding; if it should be so, no pains must be spared to make it quite true, for upon that depends the door being flat and true when put together.

Having prepared your stiles and rails for the operation, get a double-tooth mortise-gauge, and adjust the teeth so that the chisel will just lie between the extreme points; then set your gauge so that it marks the mortise in the middle; then square across your shoulders and mortises. Care should be taken to leave a sufficient haunching at the end of the mortise, otherwise when the tenon is driven into it the end will split out. Then gauge both mortise and tenons. The faced side should be marked, and always worked from.

It is immaterial whether the mortises are made or the tenons are cut first, as they are both independent operations. When cutting the tenons, place them all together and fix them in the screw, and commence cutting with the tenon-saw just outside the gauge-line, from one corner to the other, and down to the shoulder; then turn them round, and insert the point of the saw into the cut, as it serves for a guide, and finish down to the shoulder. In cutting the shoulders, cut outside the line. The saw should incline a little, so as to cut a trifle under, which will insure a good joint outside when cramped up.

In mortising, place all the pieces together on the bench, and put a hand-screw on the end to keep them close together and firm; then screw them down with the holdfast, and begin by boring a hole in the middle of the mortise down to the desired depth. The best bits for the purpose are the American twist-bits, as they cut easy and clean. It is requisite to have a set of these bits, and a dowel-plate to match, which can be procured at any of the London tool-shops, and the use of which will be treated of elsewhere. Then commence with the mortise chisel, keeping it perfectly perpendicular, and moving the handle a little from front to back after each successive blow with the mallet.

In mortising soft wood, take a cut of about one-eighth of an inch, and in hard wood not quite so much. Cut the end of each mortise down perfectly square, then pick out the core with a smaller chisel.

In joiners’ work, they usually mortise right through the stiles and wedge up; but for cabinet work, which is always inside the house and not exposed to the weather, this is not required, except in special cases.

It is usual in cabinet work to mortise about halfway through the stile, the work then being of sufficient strength, if properly done; and it certainly looks more sightly than do the ends of the tenons, and is done in half the time.

In fitting the tenon, it should be marked a sixteenth wider than the mortise, as it will then drive in tight. After fitting, the tenon should be made warm at the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Woodworking

- Preface

- Contents

- The Cabinet-Maker’s Guide

- Index