![]()

12

Voices of Temple Street

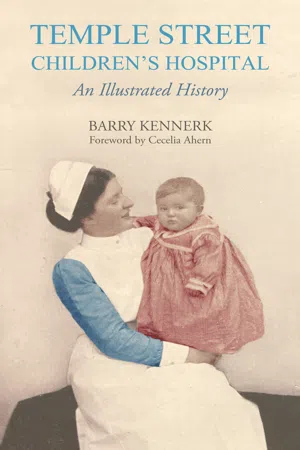

Baby Phyllis Gaffney, pictured here in April/May 1952. She was Temple Street’s first incubator baby. In October 1951, her eldest brother died in a drowning accident. Less than three months later, her father was killed in an Aer Lingus plane crash in Snowdonia. As a consequence of her mother’s shock, Baby Phyllis stopped gaining weight in utero. When she was born on 30 March 1952 in a nursing home in Galway weighing just 2.5lbs, her grandfather drove her to Temple Street, accompanied by a nurse. She remained an inpatient for four to six weeks. (Hospital collection)

![]()

Temple Street Hospital relies on a diverse group of professionals to look after the children in its care. Every day, the service is sustained not just through the efforts of medical personnel but also by the work of canteen staff, hospital porters, household staff, maintenance personnel and administrators, each of whom have their own part to play. In many ways, the hospital is like a small town – home to 1,100 people. These interviews reflect the diversity of the patient and staff experience.

The Emergency Consultant

Dr Peter Keenan, 21 March 1991. (Picture courtesy of National Library Photographic Archive)

Dr Peter Keenan (aged sixty-three) is one of Ireland’s best-known emergency consultants. Having trained in various hospitals in the UK and Ireland, he was the first doctor to hold a paediatric A&E post in Ireland. He spent twenty-seven years at Temple Street from 1984 to 2011. During that time, he treated everything from bumps and breaks to coughs and colds and witnessed the emergence of a multi-cultural community in the north inner city.

My father was born in a flat on Mountjoy Square in 1913. Afterwards he was reared with his three brothers in Nottingham Street on the North Strand. When he was about eight years old, he and one of his brothers were walked up to Temple Street by their mother via Nerney’s Court and into the outpatients department to have their tonsils and adenoids removed under chloroform or ether. His memory of it was that some kind of material – a bandage or cotton wool for soakage – was shoved into his mouth because he was pouring blood. Afterwards, they were put into a horse and trap for the trip back to Nottingham Street.

I was born in 1951. I was also admitted to Temple Street for about a week when I was about four months old. In later years, I found a very brief note in the records that read, ‘Five-month-old child – screaming a lot’ (familiar symptomatology). The next note read ‘circumcision; home’. In other words, if all else fails, do something.

I went to secondary school at Colaiste Mhuire in nearby Parnell Square. While I was there I joined the Legion of Mary and one of the things we did was to bring kids from the local tenements to Mass on Sunday morning in the Pro Cathedral. We also did Sunday morning visitations in Temple Street as part of our ‘charitable works’. In those days, parents were told, ‘Ok, leave him with us now and don’t come to visit’. I can clearly remember being up in St. Patrick’s Ward playing with the little toddlers in their iron barred cots.

In 1984, I had started in general practice at Lucan, County Dublin when the first paediatric emergency job in the country was advertised at Temple Street. I knew the hospital well. In 1977, I had worked there as a casualty officer for six months, returning the following year to do another stint as registrar under Professor Niall O’Doherty – a troubled genius and a very entertaining man with a deep interest in inherited syndromes.

When I started in the new consultancy post, they couldn’t have fashioned a better job because if I had any kind of gift, it was that I was versatile. Some people are lucky and end up as a round peg in a round hole; in other words, they get a job that really suits them, but a substantial number of the human race are not so fortunate. If I had ended up being a specialist, I might not have been so good at it but I am a bit of a DIY man. I was suited to A&E, where I had to stand back and say, well if I go completely linear with this, it just won’t work.

In the beginning, the department was tiny and always packed with people. It was little more than a tiled corridor with people sitting on chairs and a dressing room that had a number of little alcoves in it. You could barely turn – if you needed to go in and stitch something, you had to walk in and reverse out. We were seeing patients two at a time, all the time. At times, you would be sitting at a table talking to a mother and examining a child’s chest or ears or throat and a yard behind you, the surgical registrar would be holding down a child who was roaring and screaming as he tried to stitch him up.

In the mornings, I used to park my Ford Anglia beside St. George’s Church, but as a precaution I always took the coil out of it. I often came back in the evening time to find a gang of local kids sitting in it. Over the years, I got to know many of them as regular A&E attendees. You’d often have some form of banter with them or their parents based on what kind of relationship you had. When they saw me, some of them would protest, ‘Now don’t be giving out to me. You threw me out the last time’ and I’d say ‘I’ll throw you out again if you’re not careful – very fast’. So we had this adversarial relationship that would be intimate and verbal with a lot of badinage going on.

I was always amazed by Dublin malapropisms. There’s a skin infection called impetigo which is caused by bacteria in the skin. In the old days, it used to be called ‘school sores’. Time and time again, I explained to the parents:

‘He has impetigo.’

The mother would hit her husband on the arm:

‘I told you. It’s infantago!’

‘No’, I repeated, ‘it’s impetigo’.

‘I know doctor; he has infantago’.

I grew to love ‘infantago’ so much I would actually manipulate people to say it.

Then there was the whole mythology of illness. After a seizure, you might hear a mother say, ‘I thought he was going to swalley his tongue’. I used to explain that nobody ever swallowed their tongue. It was all rubbish but nevertheless it was a privilege to get the chance to disabuse parents of such misconceptions. Another time, a child would arrive in with a big lump on his head; mother and grandmother in tow. After taking a careful look, I would explain it was unlikely he had a fracture and that there was nothing to suggest he had injured his brain. The grandmother would turn to her daughter and say:

‘I told yeh. Once the bump came out the outside; that took the pressure off’.

The reasoning was incredible. It was almost Einsteinian – the dissipation of energy got carried out with the bump. It was all garbage but it made a certain amount of folk sense.

During the late eighties and early nineties, there was a meningitis scare. We saw huge numbers of patients and at one point I was on my feet for a whole weekend. There was a lot of confusion among the general public – the idea that if you had been in contact with somebody who knew somebody else with meningitis, you might catch it.

Then, two children from different halting sites on the fringes of the north city caught it and the travelling community arrived in droves. The laneway down to casualty was chockablock with vans because they had been told by the public health people to come in and get preventative antibiotics. It was completely unnecessary but the travellers were very difficult to reassure – they wanted to have their children seen and it was difficult to send them home so we had to open the assembly hall to accommodate them.

It was a bit like one of those Western movies with Elmer Gantry or Burt Lancaster where people sell snake-oil medicine from covered wagons. I was up on stage trying to address the masses that filled the hall:

‘It is really only necessary to have the antibiotic if you had kissing contact’.

It was like a biblical scene with big traveller mothers, fathers and children all over the place. One woman stood with her arms outstretched imploring:

‘Doctor, save the children!’

And I shouted back, ‘We’ve run out of antibiotics. We’ll have more later on!’

During the 1990s, there was a wave of immigration. Suddenly it wasn’t Sean O’Casey’s Dublin anymore. By talking to the West Africans I found that some were from ex-French colonies such as the Congo, Cote D’Ivoire, Senegal and I have a bit of French so I enjoyed speaking to them. The other thing I noted was their evangelical Christianity. On one occasion, a Nigerian woman came in with a chesty child. I quickly realised that he had mild asthma, which is a common enough problem. Oftentimes, it is easier for doctors to treat it with antibiotics than to explain that it is a wheezing illness that will come and go. ‘What your child has is not an infection’, I explained. ‘He has been on antibiotics and they are not working. The noise you are hearing in his chest is an obstruction as he tries to get rid of air out of his lungs. This is called asthma’. I got distracted then but when I came back she seemed quite distressed and was chanting something.

‘What are you doing?’ I asked. ‘Are you praying?’

‘Yes’, she said. ‘I am praying doctor. I am saying, Jesus I reject asthma; Jesus, I reject asthma!’

Oftentimes, antibiotics are ineffective but it is uncomfortable to see child who is distressed, particularly at night when everybody loses sleep. It’s very hard to tell people: ‘it might get worse; it might come back but there’s nothing I can give you’. You’d be talking to one family like that and out of the corner of your eye, you could see that the child in the next bed had the same thing. ‘Did you hear that?’ I used to say. ‘Did you hear what I said to that mother? And she’d say, ‘Yeah, I was listening ’, and I’d say ‘Well it’s exactly what I’m going to say to you’. That’s a very hard message to sell. On the other hand, the tendency to overprescribe has been the driving force of the greatest amount of mythology and garbage as well as putting doctors on pedestals.

When drugs came in, the aftermath was very hard to deal with. It is extraordinary to think that a child might be born to a heroin or methadone-addicted mother and need to be detoxed in the newborn baby unit in the Rotunda using Valium and other drugs and still be shaking from withdrawal symptoms for three weeks until they are feeding OK and not jittery anymore. Then they’re handed straight back into the same environment – cold, threadbare, filthy, vermin-infested, nothing but bits of bread and biscuits, no nourishment in the place; the parents bombed out; they really haven’t a prayer.

During the early nineties, I attended a conference with one of our social workers in Strasbourg. The Danes were actually talking about taking children away from addicts at birth. Some of the so-called more advanced societies would tell parents: ‘We don’t think that you are actually fit to be in charge of one of our citizens’.

Today, there is a sense that the child is the possession of the parents and that the state is big brother. I don’t think we serve the newborn citizen very well in terms...