- 300 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

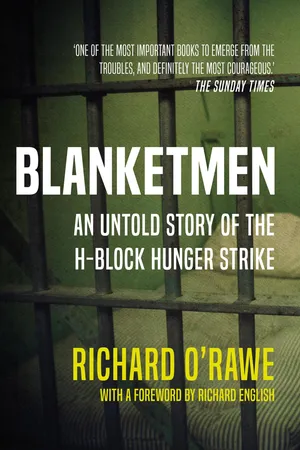

Blanketmen

About this book

Richard O'Rawe was a senior IRA prisoner in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh Prison. One of the 'Blanketmen', he took part in the dirty protests that led to the hunger strikes of the early 1980s. In Blanketmen, O'Rawe gives his personal account of those turbulent times that saw British and Irish governments entering unprecedented negotiations with the IRA Army Council and the prisoners themselves. Passionate, disturbing and controversial, this remains a landmark book in the cruel history of Northern Ireland. After ten years, and the release of historical state and personal papers, Richard O'Rawe's assertions in Blanketmen have been vindicated. He has been married to Bernadette for forty years, has three grown-up children, and still lives in west Belfast.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

‘Take a good look at it, Rick. If we go ahead with this job, we’re not goin’ to be seein’ it for a long time,’ my friend Dollhead said.

Involuntarily, my eyes scrutinised the top of Belfast’s Whiterock Road, the tiny commercial heart of the Greater Ballymurphy area. Before me was a threadbare tapestry of nondescript shops, a bar surrounded by a protective cage of grey wire mesh, the ubiquitous Chinese takeaway, and graffiti-covered walls. It was hardly the Champs-Elysées – but it was home.

‘What makes ya think we’ll not be seein’ it for a long time?’

‘’Cause this job’s a fuckin’ suicide mission! Rick, have ya done a dummy run on it?’

‘Nah, I haven’t. Jesus Christ, Dollhead, this isn’t like you at all. It can’t be that bad, surely. Fuck sake, it’s just a shitty oul’ bank robbery!’

‘Shitty oul’ bank robbery, my balls! Rick, I swear to God, it is that bad, an’ worse. Have ya any idea how far away Mallusk is?’

‘Nope, an’ I don’t care. The job has to be done, an’ that’s it. An’ we’ve been told to do it, so we’ve no choice.’

‘Well, wait till I tell ya something: I’m not doin’ it. No fuckin’ way. Mark these words, Rick: if we rob this bank, we’ll not be back here for a long time – if we come back at all. I’ll resign from the ’RA before I’ll do this bank.’

‘Hell’s bells, I’ve never seen ya like this.’

‘Do a dummy run, Rick. Just do it,’ Dollhead said, and walked away up Dermotthill.

I watched him until he disappeared around the bend at the bottom of the Dermotthill Estate, wondering all the while why he was so spooked by the prospect of robbing this bank – an operation which, relatively speaking, was on the lower rungs of IRA activity.

I went over and sat on the concrete surround of the grass verge at the bottom of the estate. All around me people were going about their daily business, unaware that I was observing them. Kevin ‘Whack’ McGettigan and Paddy ‘The Prod’ McMullan were pressing the buzzer on the steel door at the side of Kelly’s bar in the hope of gaining entry to get ‘the cure’; the two lads looked like they needed it. I noticed wee Lily Hall coming out of McAulfield’s butcher’s and then walking the short distance to McAvoy’s grocery shop, while Geordie Finn was going into the post office to collect his customers’ dole money. (Geordie would collect people’s dole and deliver it to their houses for a small fee.)

It was on occasions like this that I envied the much-maligned residents of Ballymurphy: I was jealous of their routine lives and their ability to confront the misfortune of having been born the unwanted children of a state that viewed them as whinging malcontents and rebels. Not one of them had to deal with the dangers of robbing a bank in two days’ time, or sweat a comrade’s sixth sense, which screamed at him that to go ahead with this robbery meant either imprisonment or death. Sometimes, when I sat back and looked at the way my life was panning out, I regretted having inherited my father’s passion for rebellion and revolution, for forcing the British to leave Ireland through armed struggle. (This passion was the reason I had joined the Provisional IRA at the age of seventeen in March 1971.) But those regrets were always suppressed by my desire to end British rule in the North of Ireland and to establish a thirty-two-county socialist Republic.

As I watched people go about their business, my mind turned once again to the coming bank robbery. There was a job to be done, and no amount of hocus-pocus would alter that fact: I had to put Dollhead’s mystic reticence to bed. There was no room for negative thinking: an operation was an operation, even if it was only a ‘shitty oul’ bank robbery’. And besides, this was my opportunity to make amends for an earlier faux pas.

On that occasion, another volunteer and I had gotten drunk in Kelly’s bar, and when we ran out of money we decided to do a ‘homer’, which is an IRA euphemism for a self-gain robbery. We borrowed a sympathiser’s vehicle, one that most Volunteers in our battalion knew to have been used regularly by the Ballymurphy Volunteers, and drove down the Falls Road. We robbed the first place that caught our eye. We were unmasked while doing the robbery and, while the RUC was not informed of the robbery, the IRA was. Within a couple of hours it had traced the vehicle and identified us (unbeknown to us). We got less than fifty pounds from the robbery and we blew it on drink that night. It was the dearest drink I’ve ever had in my life.

We were both shot for our misdemeanour, and rightly so. Drunk or not, we had brought the IRA into disrepute. Although we were only meant to be grazed in one leg, the bullet had gone straight through my right leg and had hit a bone on my left leg. My friend suffered an even worse fate: the bullet shattered his right leg, leaving him with a permanent limp. (Another friend, who was shot along with us, was only grazed.) Fortunately, the IRA had phoned for an ambulance before we were shot, and we were quickly transported to the Royal Victoria Hospital.

I had been married only a week when I was shot (the IRA had delayed my punishment until after my wedding). In fact, I was shot within two hours of returning from my honeymoon in Dublin. My wife, Bernie, was just eighteen years old, but her years belied her wisdom. She kept saying that we would get through this and that we would come out stronger on the other side. She never once asked me why I would do such a silly thing when I was on the threshold of pledging myself to her for the rest of my life.

Months later, though, she confessed that I had ‘badly hurt’ her. Surprisingly, this was not because I had done the homer – she had put that down to a drunken escapade. It was because when she and my father had come into the hospital ward, I had asked her to wait outside while I poured my heart out to him. I didn’t realise it at the time, but I had been extremely thoughtless – I had inadvertently devalued her and given her the impression that she did not matter, that my father’s feelings were more important than hers. My father had been a lifelong republican. Because of my overwhelming need to beg his forgiveness, I had completely ignored the possibility that it must have been a terrible ordeal for Bernie to have to see her husband of one week lying in a hospital bed, having been shot and disgraced by his own organisation.

When my father came into the ward later that day, I cried a bucketful of tears. I will never forget the pained look on his face. I couldn’t apologise enough to him, knowing that I had betrayed him as a son and had let down the family – let alone the great dishonour I had brought on myself. He saw that I was hurting and tried to comfort me by saying that life was about learning from, and living with, mistakes, that anyone could make a mistake, and that I wasn’t the first and wouldn’t be the last to mess up. He hugged me and told me not to worry, that this pain would pass. I so much wanted to hear those words, even though they failed to lessen my feelings of self-detestation or assuage my guilt at having brought shame on my family. I hated myself.

I was released from hospital after a week and refused to leave the house for a couple of weeks. How could I face those good people who had put their trust in me down through the years? A couple of Volunteers called to the house in a car and insisted that I go with them to Kelly’s bar for a drink. I reluctantly agreed. When we got there, I was treated very well by everyone and, after a few beers, I felt at home again as the formal greetings gave way to a bout of serious ribbing about my having been shot. It was as well that I was thick-skinned.

I had one abiding objective, one avenue left along which I could salvage my honour and self-respect, and that was to get back into the IRA as quickly as possible. I had found life outside the IRA difficult to adjust to: all my friends and comrades were still in it, and I felt a certain jealousy when I saw them discussing IRA matters to which I was no longer privy. Although I was ideologically committed to the cause, for me, in many ways, being in the IRA was almost the objective rather than the means. I missed the sense of belonging, the comradeship, even the conspiratorial nature of the IRA’s procedures. I was still a very committed republican: the struggle had been my life, and I dearly wanted, if the IRA would take me back, to be given the opportunity to atone for my mistake.

After three months, I approached the man who had engineered my punishment and told him that I wanted to be readmitted to the fold. He laughed and told me that there would be no problem. I was back where I belonged.

Two days after our conversation, I met Dollhead early in the morning at the top of the Whiterock Road. It was February 1977, dark and cold, and it was bank-robbery day. There was a wry smile on his face.

‘There it is, Rick,’ he said. ‘The top of the ’Rock. You’re not goin’ to see it for a long time.’

‘Wise up. You’re puttin’ the scud on us, an’ we haven’t even started yet.’

‘We’re goin’ down for this one, Rick.’

I wasn’t in the least surprised to find Dollhead ready and willing to do a job that frightened the life out of him. He was always going to do this operation, no matter what he had said earlier; his sense of duty to the IRA allowed for nothing else.

We climbed into the white van. There were four of us in the van, all experienced men who had faced this type of pressure many times before. It had been decided that we wouldn’t wear gloves until we’d left the van to rob the bank, in case the police – or ‘Peelers’, as they were more commonly known – stopped us on the way. I was sitting in the front alongside Dollhead, our driver, and made a point of touching nothing. The weapons were in another vehicle, behind us, so that if we were stopped, at least we’d be clean – although, considering the calibre and history of the men in the van, we would be arrested and taken to Castlereagh Interrogation Centre at the very least.

We crossed over to north Belfast. We drove up the never-ending Antrim Road, past the urban New Lodge and the North Circular Road area with its grand detached houses. Soon Bellevue Zoo was behind us. I looked quizzically at Dollhead, but he only shook his head and grunted: ‘I told ya, didn’t I?’ I had no reply, but Willie John McAllister wasn’t so taciturn.

‘In the name of Jesus, where’s this bank?’ he asked.

‘Willie John, we’re nowhere near it,’ Dollhead said.

‘For fuck’s sake, if we go any farther away from Belfast, we’ll end up in Ballycastle. We must have passed a dozen banks already to get here. Look, there’s another one.’

Finally, we came to a halt outside Glengormley village. A female Volunteer left the second vehicle and got into our van. She produced the guns, surgical gloves and pillowcase – the bank robber’s tools. After putting on the gloves, we stuck the guns down the backs of our trousers and drove on. We arrived outside the Northern Bank at Mallusk at eleven o’clock. I had never heard of Mallusk before this operation had been proposed, and had no idea where we were. All I knew was that we were miles from the safety of Ballymurphy.

We left the van as any workers would, laughing and patting each other on the back, but that was all for show. Behind the smiles and merriment was the tension that comes when an operation is about to take place.

Everybody had been allocated a job. Willie John was to scoop the money. Another man was to help me to frighten the staff into obeying our orders. I had overall charge of the robbery in the bank, as well as covering the door. Dollhead would remain outside in the van, along with the female Volunteer.

When we entered the bank, Willie John went up to the top of the customers’ area and the second man pretended to fill in a form in the middle of the bank. They both gave me the nod that they were ready. I put my hand around the back of my waistband and produced the gun.

‘Nobody move! This is a robbery! Get away from that counter or I’ll fuckin’ blow your heads off!’ I shouted as loudly as I could, pointing the gun menacingly at the bank staff.

While the second man ordered all the customers to lie down on the floor, Willie John had a gun pointed at a bank employee and was ordering him to open a door leading into the back of the bank.

The side door was opened and Willie John was in behind the counter in a flash, scooping money from the various teller slots. He then disappeared into the farther reaches of the bank, where I assumed the safe was located.

There is always a period in a bank robbery when the initial threat of violence gives way to the business at hand, as staff and robbers alike resign themselves to getting the ordeal over with as quickly as possible. I was standing at the side of the front door, and although I kept barking orders to ensure control over the staff and customers, I felt very calm and was pleased that things were progressing nicely. An old lady, who was standing at the first teller slot, was in a bit of distress, so I went over to her and told her she had nothing to worry about, that we were only interested in the money and that she was in no danger. She said, ‘Thank you, son,’ and seemed more settled. A large man entered the bank, and I put the gun to his head and shouted at him to put his arms up before making him stretch out on the floor. I then frisked him to see if he was carrying a weapon.

The whole thing was taking too long, and I shouted for the ‘number three’ (Willie John) to hurry up. For the duration of the robbery I had my hand covering my mouth and face so that, even if there was a hidden camera – and I couldn’t see one – at least they would not get a clear image of me.

Finally, Willie John emerged from behind the counter. One last warning that nobody should move, and we were out of the bank. We walked quickly to the van and jumped in. As the van took off, the guns and gloves were put into the pillowcase, along with the money, and the pillowcase was then shoved into a tw...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword to the 2016 Edition

- Prologue

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Blanketmen by Richard O'Rawe,Richard O'Rawe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.