![]()

AFTERWORD

Milestone to Monument:

A Personal Journey in Search of Francis Ledwidge

Dermot Bolger

For Donal Haughey

At the most unlikely times I think of the Irish poet, Francis Ledwidge. Maybe when playing tennis with my sons in a Dublin park or driving home late at night, opening my hall door, knowing that my wife is asleep upstairs. These simple acts were these futures that he missed, these mundane yet magical realities that he might have expected to know. Most Fridays I still play football on astro-turf near Dublin Airport. My ankles and back are gone but I pretend to cheat time a little longer because I want to prolong this brief plateau when my sons and I can share the one pitch.

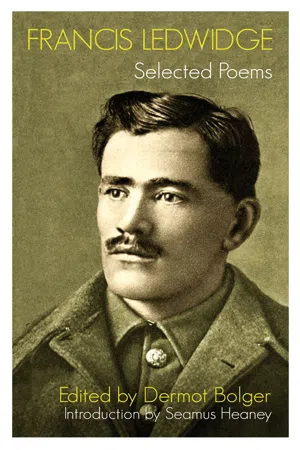

Occasionally, I look beyond the floodlights at the planes landing and think of Ledwidge. He never knew a son or a wife for that matter. He never felt the need to cheat time, because time cheated him. Fate tackled him from behind, just a few weeks shy of his thirtieth birthday, when he was blown to pieces in Flanders by a stray shell during a lull in the first day of the nightmare Third Battle of Ypres. Whatever shattered parts of his limbs that could be gathered up were dumped in the crater left by that shell before the work of road building recommenced. His face became trapped inside a handful of photographs. He looks out at me from those old photos still, trapped in an innocence that he longed to shed, condemned to the limbo of being forever young.

However, like thousands of fellow Irishmen, Ledwidge was also condemned to another kind of limbo. Rupert Brooke’s death in the First World War immortalised him at home. It was the same for other war poets like Wilfred Owens or the Canadian, John McCrea, whose poem, In Flanders Fields, features on the Canadian $10 bill. Their posthumous reputation was simple; there was no legacy of divided loyalties, no whispered rumours. The Britain to which poets like Siegfried Sassoon and David Jones returned home might, with time, nurse ambivalent feelings towards how ‘great’ that war was, but such survivors were never viewed as traitors; they could publicly talk about their experiences. Their stories were not blotted out of the national collective memory in their countries or from many histories of the period, with books like T.W. Moody and F.X. Martin’s The Course of Irish History reducing the Great War to essentially a couple of lines about John Redmond’s recruiting speech. It is only in recent years that the war experiences and motivations of Irish men like Ledwidge are being fully explored.

When I try to recall my first encounter with Francis Ledwidge, he is not the only ghost that I need to conjure up. A second ghost lurks in my mind, aged sixteen, a year younger than Ledwidge was when he wrote his first proper poem. It is the ghost of my younger self, deeply impressionable and insecure, reaching out blindly towards a future that I could hardly dare imagine. I imagine two very different walks home by teenage Irish boys born seventy-two years apart. Both walk the same road north from Dublin City for three miles until they reach my native village of Finglas – then Ledwidge walks on through the darkness of the North Road towards his own village of Slane, on a journey that I can only follow in my imagination. This afterword is not just about Ledwidge’s life, his place in Irish literature and the place which he, and the thousands of other Irishmen who died in the First World War, were allotted in history. For me, it is also about how you can encounter a poet in your youth who remains an enduring touchstone in your life.

Ledwidge’s walk home as a seventeen-year-old occurs in the autumn of 1904. The social highlight of that year in Dublin was the contested visit of Edward VII and Queen Alexandra to Ireland, with elaborate displays of loyalty mingling with nationalist protests, inflamed by the growing success of the Gaelic League. By far the most important date in Dublin in 1904, however, was 16 June – though perhaps even Joyce himself didn’t know it – when a penniless James Joyce first walked out his great love, Nora Barnacle, with both of them soon to embark on a new life together in Europe. I suspect that in Slane the fact that the Abbey Theatre was about to open its doors in Dublin with premieres of On Baile’s Strand by W.B. Yeats and Spreading the News by Lady Gregory was not much discussed. But what probably was being discussed was the news of how a local boy, Francis Ledwidge – the likeable son of a widow whose family were much visited by hardship – had landed himself a position as a grocer’s apprentice in Rathfarnham, a township on the far edge of the city of Dublin. Grocers have got a raw deal in Irish literature, ever since Yeats depicted them fumbling in greasy tills. Mr W.T. Daly, our dour Rathfarnham grocer, fares little better. A forbidding, unfriendly man (who ran a large business with a grocery shop at one end of his premises and a licensed public house at the other), his gruff manner seems to have merely increased Francis Ledwidge’s homesickness.

Sixty years later, another young Irish country person who came to Dublin with dreams of literary fame would also endure the tedium of life behind a shop counter. In The Country Girls, Edna O’Brien’s 1960s act of rebellion was to secretly dye her bra black in the tiny bedroom above the chemist shop where she worked in Cabra. Ledwidge’s act of rebellion in 1904 was less dramatic, but it still permanently closed the door for him on the joys of a retail career.

So consumed with loneliness that he could not sleep in his room above Daly’s shop in Rathfarnham, Ledwidge found himself composing his first proper poem, a montage of remembered sights of his native village. After finishing the poem he was filled with restless energy and exhilaration, a new sense of power. Taking his meagre belongings, he crept down through the closed shop, passing its chests of Indian tea, its rows of drawers for spices and grass seeds, its menacing ranks of long boots hanging from the ceiling. He closed the door, terrified that his employer would hear. Walking back down off the foothills of the Dublin Mountains into Dublin City, he found the long straight road, out past Glasnevin cemetery and Finglas village, to Slane. This walk of almost forty miles from Rathfarnham would bring him back to his impoverished mother, his younger brother, Joe, and to the cottage where he had known penury, attempted eviction, starvation and the death of his oldest brother. But within the small rooms of that labourer’s cottage there beckoned the irreplaceable sense of home.

In comparison, my own walk at sixteen is decidedly more mundane. In 1975 I walk out the same long road past the tombs of clerical princelings inside the railings of Glasnevin cemetery, and up the steep dual carriageway that replaced the woodland road to Finglas village. My reason for walking home is that I have spent my bus fare and all my savings on the biography of a poet who died in the First World War named Francis Ledwidge. I read this biography by Alice Curtayne with growing curiosity as I walk. At sixteen I need to know that someone else once felt same the way about words as I feel. I crave reassurance, some affinity in my confusion at having become obsessed with the alchemy of verse. I need a hand to reach out – living or dead – and say, ‘I have come this way too. Follow your dreams, believe you can write.’

Ledwidge’s rural village of Slane was utterly different from the tough working-class suburb of Finglas. But I realised that Ledwidge would have passed through the main street of Finglas, with the only sounds being his footsteps or a dog barking. A few hundred yards past the police station he would have stopped in the darkness of the North Road to rest on a Royal Mail milestone placed here. Curtayne’s biography claimed that during his walk home at seventeen he stopped at every milestone between Dublin and Slane. His fingers would have traced out the distance still to walk, knowing that he was throwing away his mother’s hopes of an escape from poverty as he chose to return with nothing except this first poem.

On the night I bought Alice Curtayne’s book I went walking and found that – amid all the development that transformed Finglas into a vast, haphazard suburb – that same milestone had miraculously survived. I sat on the stone and closed my eyes to envisage Ledwidge. In my adolescent state, I wanted his ghost to haunt me, his unwritten poems to come through me. I opened my eyes and watched trucks thunder past towards Slane and swore that some night I too would walk out along that road and replicate his journey to Slane. In my adolescent state I convinced myself that, if I retraced his steps and arrived at his cottage at dawn, I would then know how a poet truly felt.

As Curtayne details in her biography (to which I owe a great debt of gratitude for much of the information here), Francis Ledwidge was born to country parents in 1887 in a labourer’s cottage in Slane, the second youngest of nine children. His father, Patrick – who died when Ledwidge was four years old – was a migrant agricultural labourer, a profession where you could slave into your eighties and still be referred to as the ‘boy’. Ledwidge’s cottage was built by the Rural District Council and came with half an acre of garden, presumably to help the inhabitants become self-sufficient. Today his garden in Slane is beautifully kept, as part of a small cottage museum, yet whenever I walk through it I don’t think of beauty but of suffering. The orphanages of early Twentieth Century Ireland were crammed with children – but not necessarily with orphans. For parents unable to cope, the only option was often to pay a visit to them with your child wrapped in a shawl and walk out with your hands cradling an absence.

Anne Ledwidge’s neighbours were clear about her best course of action when her husband died suddenly, leaving her utterly destitute. Francis and his brother Joe, who was only three months old, should be put into an institution while she tried to raise the other children at home. Older prisoners in Stalin’s gulags used to talk nostalgically about former incarcerations, then sigh with fond memory and say, ‘Ah, but that was a Tsarist jail!’ Likewise, Irish orphanages before independence may possibly not have been as bad as the brutalised exploitative factory farms which some Irish religious orders later ran using child slave labour, with little interference from the new state. However, I doubt if any former inmates recalled them nostalgically.

I doubt also if poetry could have survived within Ledwidge had he and his brother been given numbers instead of names behind the bars of an orphanage. However, Anne Ledwidge decided to keep her two youngest sons at home by working during every hour of daylight in the fields around Slane for two shillings and sixpence a day. Francis and Joe – when he grew old enough – would join her after school as she slaved at backbreaking tasks like thinning turnips or potato picking. When darkness fell they could walk back to the cottage, where finally there would be warmth, some food and, if they begged her, stories.

By knitting, washing and mending in winter Anne Ledwidge kept her family together, while managing with great difficulty to educate her eldest son, Patrick, until he secured an office job in Dublin and became the bread-winner. Briefly it seemed that she could spend more time with her young children, but after a spell in Dublin, Patrick returned home, an invalid dying slowly of tuberculosis. Ledwidge wrote about the following four years: ‘it was as though God forgot us.’ When bailiffs arrived to evict the family they survived only because a doctor testified that Patrick was too ill to be moved. When he died the family lacked the money even for a coffin.

It puzzles me why some people have a mania for making Ledwidge’s life picturesque. Certainly the land around Slane is as lush as Flanders is today and a thin cow in Meath would be a tourist. But land is only good if you possess it. There is nothing picturesque for a child in seeing bailiffs come to evict your family or watching your brother die slowly in the back room where you can barely concentrate on his suffering because of your own hunger. To see your mother grow haggard from kneeling in a muddy field, or watch her hands turn blue from scrubbing at other people’s washing, or trying to darn by the light of a meagre fire, is not picturesque – no matter how much we prefer to dickey up the rural past as a cosy and simple world.

Large families were instinctive among the poor everywhere, not just due to the lack of contraception, but also as a sort of insurance policy because there was a strong probability that not all your children would survive. Child mortality rates were higher in Dublin during Ledwidge’s day than they were in Calcutta. My own father remembers, as a boy in 1920s Wexford, being sent out onto the road to wait while his eldest brother slowly died. He rarely speaks of it, but no child could forget such a thing.

What did Ledwidge remember or want to forget about his brother’s death? Was he sent out with Joe into the garden so as not to hear the last rasping breath? We don’t know because his poems don’t actually tell us. He wrote no poems about his brother’s coffin, his mother’s worn hands, his desperate childhood hunger. Instead we get detailed descriptions of birds, flowers and fauna, all the elaborate paraphernalia that constituted High Georgian verse. We get the middle-class mannerisms of his betters being parroted by this relatively uneducated young man who sat up late at night to write in his cramped cottage, his limbs weary from road repairing or doing the same labouring work as his late father.

Yet, even though Ledwidge never lived long enough to fully rip aside the veil of poetic convention that often separated the artificial language of his poems from the true language of his life, there is something monumentally staggering about the audacity of someone from his class, from his occupation as a farm land and roadworker, even aspiring to being a poet. Edwardian poetry was a gentleman’s club, with well-connected ladies occasionally tolerated. Indeed, Ledwidge’s own entry into the poetry establishment would be stage-managed by a rich patron, Lord Dunsany. Dunsany, a member of the Meath aristocracy, generously befriended Ledwidge. He encouraged him, loaned him books and – without any understanding of how outrageous the phrase would seem today – marketed Ledwidge as ‘a peasant poet’.

James Joyce, who resolutely embraced the modernity of the Twentieth Century, was five years older than Ledwidge who, in contrast, seems wrapped up in the dying certainties of the Nineteenth Century. Often the Joyce family possessed little money either; however, even without cash, they remained middle-class people with connections and breeding. At around the time that Joyce as a precocious student was being praised for his essay on ‘Ibsen’s New Drama’ (with even the great Norwegian playwright himself impressed), Ledwidge was leaving school at thirteen. He left on the morning after he received the Catholic sacrament of confirmation, when childhood ended abruptly. Directly behind his cottage wall he could earn seven shillings a week as a farm boy working from dawn to dusk on the Fitzsimons’s farm. However, Anne Ledwidge was ambitious for her children to better themselves and soon a world of grandeur beckoned for Francis.

Today Slane is associated in the public mind with rock music because of an annual concert staged in the natural amphitheatre of the grounds of Slane Castle. Inside this castle U2 waited to play to eighty thousand people. Bruce Springsteen waited to play. Bob Dylan likewise waited his turn and Francis Ledwidge simply waited his chance to wait at table – because that was what trainee houseboys did in Slane Castle while working their way up through a strict servant hierarchy. Slane Castle – heroically restored by its present owner, Lord Henry Mountcharles, after a terrible fire – dominates Slane village. The ordered layout of the village (rare in Ireland) betrays the controlling fist of the Mountcharles family. Some historians claim that the road from Dublin to Slane was straightened by royal order of George IV, who was kicking his heels in Dublin as Prince of Wales, so he might more conveniently reach his mistress, Lady Conyngham, in Slane Castle. It appears that while His Majesty appreciated Irish curves, he didn’t much care for Irish bends.

Every summer during its annual rock concert, the young people of Ireland try to do to each other, in quiet corners of the castle grounds, what the future King of England did to Lady Conyngham in more private surroundings indoors. Afterwards when concertgoers traipse back out through the village they pass street benches bearing the words ‘Ledwidge Country’. I occasionally wonder if this act by local people to re-colonise the village in the name of a farm labourer is, in some small sense, Slane’s way of putting the aristocratic family who ruled the village for centuries in their place. I wonder what the former Marquis of Conyngham (who presumably imagined that Slane was his ‘country’) would make of local housing estates being named after a penniless boy who – though I doubt if the Marquis was even aware of Ledwidge’s brief employment – once worked in his kitchens.

At fourteen Ledwidge had a propensity for mischief and he was soon dispatched back to working in the fields. Not for long, however. His mother soon fixed up an apprenticeship with a grocer in Drogheda, a town ten miles from Slane. Every Sunday Ledwidge’s younger brother Joe accompanied him to a nearby bridge from where Ledwidge walked the rest of the distance to Drogheda. His working hours often lasted until midnight. Drogheda was a small town and his mother wanted to advance his career when the chance came for him to take up his ill-fated, short-lived position with W.J. Daly in Rathfarnham. Looking back now, I suspect that Ledwidge’s story of being so stirred by writing his first poem that he abandoned his job and walked home is primarily an attempt to cloak the mundane homesickness of a young country boy who finds himself overwhelmed by the city. However, his mother never sent him back to Dublin or to shopwork. He roamed the fields and lanes seeking work and at last he struck lucky.

A few hundred yards from the famous neolithic burial chamber at Newgrange, several miles from Slane, Ledwidge found employment with a carefree young couple on a farm that today is an open farm where children learn about the countryside. For two years Ledwidge was their ‘boy’ at £21 a year, helping about the yard, driving their horse and trap and amusing his employers, the Carlyles, by his strange habit of sitting up at their kitchen table late at night to write poems. Paradise rarely lasts, however, and when the Carlyles moved away, Ledwidge found a new career at the age of nineteen.

In 1907 seasonal roadworkers start to be employed in Meath, being paid seventeen shillings and six-pence a week. In starting this new job, Ledwidge was coming up in the world and even acquired a bicycle as he laboured down tiny lanes, with a billycan to brew tea. You can’t eat nature, though, and the prospect of more money lured him into starting work as a miner when a copper mine opened in nearby...