- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

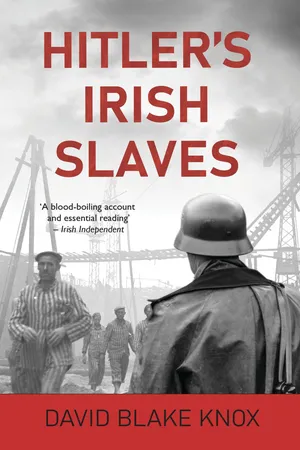

Hitler's Irish Slaves

About this book

Hitler's Irish Slaves tells the shocking story of 32 merchant seamen from Ireland who were held in conditions of great hardship in an SS slave labour camp from 1943 to 1945. Mercilessly punished for their refusal to join the German war effort, and ignored by their own government, they became part of a slave workforce that was used to construct an immense bunker. The Nazis believed that they could build a 'miracle boat' in this bunker: a new type of U-boat that could win the war for Germany. To achieve that goal, many thousands of slaves were worked to their deaths.Despite the savage regime to which they were subjected, and unlike some other Irishmen, they steadfastly refused all attempts by the SS to turn them into collaborators with the Third Reich. In this engrossing and dramatic book, David Blake Knox explores the fascinating and tragic story of the hardship endured by these men, as well as the reasons why that narrative, like the men themselves, has been unjustly neglected. Previously published as Suddenly While Abroad .

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hitler's Irish Slaves by David Blake Knox in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1.

Suddenly, While Abroad

My father began to plan his funeral about ten years before he died. He told me that he had already bought a plot in Dean’s Grange Cemetery, in south County Dublin, close to his mother’s grave. He said that he had intended to commit suicide some years previously and thought it would make sense to choose his final destination before he killed himself. To anyone who knew my father, this story was simultaneously highly implausible and all too likely to be true. He gave me a slip of paper on which he had scrawled all the relevant details, adding that he would not mind if I chose instead to put his body in a bin bag and sling it in a rubbish tip.

My father’s motives for telling me this weren’t entirely clear: certainly not to me, and probably not to him either—perhaps especially not to him. I was pretty sure that, at some level, it was bound up with the emotional mayhem that had been caused by his wartime experiences. Nonetheless, a few weeks later I was driving past Dean’s Grange, with his slip of paper in my pocket, and I decided to pull in to see if I could find his plot. It didn’t take long, although it turned out that the resting place my father had chosen for himself was a considerable distance from where his mother was buried. His choices may have been limited: the family vault was crammed full with an assortment of close and distant relatives. Pride of place on its weathered stone obelisk was given to my great-great-grandfather, Francis Blake Knox—the founder of this particular branch of the family. Although his name was carved on the grey stone, Francis was not buried in this cemetery, but in County Mayo in the west of Ireland, where he was born and where he had died.

As I turned away from the vault, I stumbled upon another, slightly smaller, grave just a few yards away. Once again, the tombstone—which, this time, took the form of a large Celtic cross—bore the name of Francis Blake Knox. That didn’t surprise me unduly: the name has been popular in my family for several generations, and was now attached to one of my own nephews. I was more perplexed by another of the inscriptions on this grave. It referred to ‘Billie’, who had apparently died in Bremen in 1945. I had never heard of this relative, and there was no reference to the circumstances of his death.

When I next saw my father, I asked him who this person might be. Judging from the spelling on the tombstone, I had thought that ‘Billie’ might be a female relative, but my father told me that it referred to ‘William Hutchinson Knox’, his cousin. ‘What happened to him?’ I asked. ‘He was killed in Germany just before the war in Europe ended.’ I was curious to know why he wasn’t called ‘Blake Knox’, but my father only muttered something about there being ‘enough of us’ in the world already. I knew from the tone of his voice that this was a subject he did not wish to discuss further. I also knew, from long experience, that the more I questioned him, the less I was likely to learn. It was only after my father’s death that I learned what had happened to our lost cousin.

I had imagined that my father’s unwillingness to talk about William was connected to his general reluctance to talk about the war in which he had fought. As a young man, my father had crossed the border from the state that was then known as ‘Eire’ into Northern Ireland soon after hostilities were declared in 1939, and enlisted in the British Army. Once again, his motives in doing so were not entirely clear to me—and probably not to him either. My father was not greatly interested in politics, but he often expressed a visceral dislike of Hitler, and he connected, with some reason, the extreme Nationalists of Nazi Germany to their contemporary equivalents in Ireland. We were not Jews, but my father held the Jewish people in high regard, and was revolted by their persecution. When he was young, Irish Jews had usually been sent to Protestant schools, and some of his classmates and friends were Jewish. Perhaps, as a member of one religious minority, in his case the Church of Ireland, he also felt some sense of identification with another.

No doubt there were other factors in the mix besides his dislike of National Socialism, such as his simple desire for excitement, and there may also have been a sort of historical reflex that led him, his two brothers and half-a-dozen cousins to volunteer for active service. His family had a tradition of serving in Irish regiments of the British Army—for the most part, in the Connaught Rangers. They were by no means the only Irish family with that custom: from the time of the Peninsular Campaign at the start of the nineteenth century, soldiers from Ireland had helped to form the backbone of Britain’s infantry divisions. The Irish government did not go to great lengths to prevent such voluntary enlistment continuing during this war; they may even have welcomed its easing of the problem of chronic unemployment at home. One memorandum from the Ministry of Justice stated succinctly that, given the ‘present economic circumstances,’ it was better for young Irish men to be in the British Army ‘than in our gaols’.

The government proved to be much less tolerant, to say the least, of the 5,000 or so Irishmen who were already serving in the Irish Army, and chose to desert to join the Allied armed forces. General Dan McKenna, the Irish chief of staff, explained these desertions in what may seem like sympathetic terms: ‘Those who have a natural taste for military life are more inclined to join the British Services,’ he wrote, ‘where a more exciting career is expected.’ The Irish government did not share his understanding. In fact, they would later deny those soldiers who had deserted the Irish Army any access to public jobs and to state pensions when they returned home. This issue would fester for many years, and would generate much ill feeling and deep resentment.

My father ended up in Burma in 1942, with the First Battalion of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. He arrived outside Rangoon just a few days before the decision was taken to evacuate and burn down that city. Rangoon was already in flames when my father joined the longest forced retreat in British military history. It lasted for more than three months, and covered over 1,000 miles of unforgiving terrain. The retreating army was under constant and ferocious attack from elite Japanese divisions as it fought its way to the Indian frontier. It suffered more than 10,000 casualties, one of whom was my father. He was hit by shrapnel from mortar fire, and his wounds turned gangrenous. Fortunately, an American missionary doctor had set up a field hospital under canvas. He operated on my father and saved his life.

General Slim described the men who limped out of Burma as ‘utterly exhausted, and riddled with malaria and dysentery.’ However, Slim could also recognise that ‘they still carried their arms, and kept their ranks.’ They may have ‘looked like scarecrows’, but Slim was proud that ‘they looked like soldiers too’. It had taken a beating, but the Fourteenth Army was still an army, and a few years later my father was lucky enough to be alive, and able to take part in the counteroffensive that drove the Japanese forces out of Burma.

He came back to live in Ireland in 1946, to a country that had remained politically neutral for the duration of the war. There were sound pragmatic reasons for the Irish government to follow that policy: apart from the human casualties it would have involved, Irish participation in the war could have exacerbated serious internal divisions in a country that was still recovering from both a bitter civil war and a deep economic depression. As a result of its neutrality, the Irish State had little direct involvement in the global conflict, and its resident citizens were even restricted in their knowledge of what had taken place. Martin Quigley, an agent in the OSS, the forerunner of the CIA, had visited Dublin for six months in 1943, and reported that for most Irish people the war in Burma and the Pacific ‘seems as remote as if it were being fought on Mars.’

Stringent censorship had accompanied political neutrality—in what was officially known in Ireland as ‘The Emergency’. In 1935 the Irish government had set up an interdepartmental committee ‘to prepare and submit proposals for the operation of censorship in time of war.’ The report it had submitted was put into effect in August of 1939. Frank Aiken, who was appointed as Minister for the Coordination of Defensive Measures at the outbreak of hostilities, claimed that part of its purpose was simply to prevent ‘our people being oppressed by a barrage of propaganda.’ However, as Clair Wills has noted, stripping reportage of the war of all editorial commentary produced ‘its own kind of falsehood.’

This was perhaps most evident in Irish cinemas, where Joseph Connolly, the new Controller of Censorship, outlined what could, and what could not, be shown to Irish audiences. His first principle was that that ‘all news films’ shown in Ireland ‘must be free of war news’. He also insisted that there must be no sight or mention of ‘war preparations, parades, troop movements, naval and aircraft movements, defence preparations, pictures of shelters [or] sandbagging.’ In addition, no comments, positive or negative, were to be permitted about ‘any of the countries engaged as belligerents.’ This was still a pre-television era, and newsreels were a primary source of information for audiences across Europe. The extraordinary constraints imposed by the Irish government created immediate problems for Gaumont Pictures, who produced weekly newsreels for both Irish and British markets. They responded to the new situation by using quite different material for the two countries.

On 16 May 1940, for example, the British version of the Gaumont newsreel covered the bombing of Rottterdam and the arrival in London of the entire Dutch government, which had fled the German blitzkrieg. The Irish version featured the Pope proclaiming a new saint in Rome and a festive carnival in Zurich. The next week, the British newsreel included the German bombing of Belgian towns and dramatic footage of terrified refugees sheltering from machine-gun fire. The Irish version featured the King of Italy being received by Pope Pius XII and the Kentucky Derby. In the years that followed, the newsreels shown in Ireland continued scrupulously to avoid screening any disturbing images of bloodshed and destruction. Instead, the patrons of Irish cinemas were kept well informed about international horse races, new arrivals in Dublin’s Zoological Gardens, and of course the Pope’s latest round of engagements. Eventually, in 1943, no further Irish editions of these newsreels were made or screened—apparently, to the great relief of Irish audiences.

Feature films were also subject to official censorship. Film distributors in Ireland were used to this, and apart from the objections to movies that featured the war, some of the other restrictions were based on traditional moralistic grounds. There was a puritanical antipathy to what the Gaelic Athletic Association termed ‘pictures extolling idleness, extravagance, superficiality and depravity of all kinds.’ Such movies, it was claimed, carried a ‘deadly, creeping poison’ that threatened the spiritual health of the Irish nation. A similar attitude led the official censor to insist that the title of the Hollywood film I Want a Divorce, described in its publicity as ‘a wise-cracking comedy’, be changed in Ireland to The Tragedy of Divorce. Some of the cuts demanded by the film censor defied any obvious explanation. In a report sent to the OSS in Washington, Martin Quigley cited the case of the RKO movie Bombardier, in which an instructor tells new recruits: ‘There are three things a bombardier must remember: hit the target, hit the target, hit the target.’ The censor insisted that the last two ‘hit the targets’ be cut. Quigley commented: ‘Don’t ask me why.’

Newspaper censorship may not have been quite as comprehensive, but the press was also strictly regulated by the government. The details of Irish soldiers who had died while serving with Allied forces could not be reported directly in Irish papers: instead, those who were killed in action had died ‘suddenly, while abroad’. When the British battleship the Prince of Wales was sunk by Japanese torpedo planes in October 1942, with the loss of 327 lives, it was referred to in one Irish newspaper as a ‘boating accident’. Even the word ‘Nazi’ was not allowed to appear in print because the use of the word outside Germany was deemed to have ‘an adverse connotation’. When Belfast was bombed in April and May of 1941, with the loss of almost 1,000 lives in one night alone, the Irish press was instructed to avoid publishing any of the ‘harrowing details’. All in all, the years of the Emergency saw what Ian Wood has described as ‘an expanding bureaucracy’ working diligently to ‘cocoon Irish people from the unsettling realities of a world at war.’

Meanwhile, the members of a ladies’ knitting circle in Killarney were questioned by the Gardaí, who suspected them of making socks and gloves for Allied troops. Small wonder that Samuel Beckett later told Israel Shenker, with his usual mordant irony, that he preferred to live in ‘France, at war, than Ireland, at peace.’

Censorship relaxed a little as the war entered its closing stages, but the most serious omission from Ireland’s press coverage obtained until the very end. This related to its atrocities, and in particular to the systematic genocide being perpetrated against Europe’s Jews. The position of the Censorship Board was stated clearly by T. J. Coyne, its deputy controller: ‘The publication of atrocity stories,’ he wrote, ‘whether true or false, can do this country no good.’ In 1942, Coyne and Aiken informed the press censors that details of specific war crimes were not to be published in Irish newspapers. In December of the same year, the Allies issued a strongly worded resolution regarding the persecution of Jews, which gave accurate details of the mass deportations that had begun in Poland, and in other occupied countries. In April of 1943, the Bermuda Conference also drew world attention to what was happening to the Jews of Europe.

Many years later, the Irish cabinet minister with special responsibility for censorship, Frank Aiken, admitted that ‘what was going on in the camps was pretty well known to us early on.’ Despite that, there were no explicit references in the Irish press to the Holocaust until after the war was over. Even after Auschwitz, Belsen and Buchenwald had been liberated, and their horrors had been exposed, no recognition of the genocide came from official Irish sources. In that context, it is hardly surprising that the first newsreels to feature footage from the death camps were greeted with considerable scepticism by Irish audiences when they were shown in Irish cinemas. Indeed, one Irish newspaper even suggested that the British had used starving Indians to play the roles of concentration camp victims. The implication was that, whatever atrocities might have occurred, they were being cynically used to mask the real culprit, and that was the old enemy: British colonialism.

I remember, towards the end of his life, my father passing my son, Jamie, a faded photograph. It had been taken outside the Red Fort in New Delhi in 1941, and it showed eight young men. Six of them were sitting in a row of chairs. Two men stood directly behind them. I recognised one of these as my father. ‘Who are they?’ my son asked.

‘My brothers,’ my father answered. Seven of the men were second lieutenants in my father’s battalion; the eighth was their commanding officer. They had all recently arrived in India after several months cooped up on a transport ship. My father looked like one of the eldest in the group, and he was just twenty-three when the picture was taken. Under the feet of four of the men who were sitting down, he had marked a cross. Another cross had been drawn above the head of the man standing beside him in the back row. My father pointed to a good-looking young man with fair hair, who was seated in front of him: ‘My best friend, Pat Kelly. He was the first we lost.’ He took the photo from my son and held it close to his eyes. ‘We lost him the week after his birthday,’ he said. ‘We had given him a bit of a party to celebrate. The next week he didn’t come back from a night patrol. I found him two days later.’ Kelly had been stripped, tied to a tree and disemboweled. My father managed to send a letter to my mother: ‘I have seen a terrible thing,’ he wrote, ‘and I don’t think I will ever be the same again.’

Much later, I found out that Patrick William Kelly was the son of a Church of Ireland clergyman. He had been educated at Mountjoy School in Dublin (the school became Mount Temple Comprehensive in 1972, and its future pupils would include Bono and the rest of U2). Pat Kelly graduated from Trinity College, Dublin, shortly before the war broke out. He travelled north with my father, and they enlisted and were commissioned in the same Irish regiment. They trained together in the military academy at Sandhurst, and travelled to India on the same troop ship. Pat Kelly was killed less than a month after they arrived in Burma: he had just turned twenty-four. ‘After that,’ my father told me, ‘I never minded killing Japs.’

The men and women who had spent the war years in Ireland might be forgiven for failing to understand the sort of lasting trauma, both physical and emotional, that Irishmen like my father had endured in Burma, and in the other operational theatres. And the lack of understanding could work in both directions. The Emergency had promoted a sense of national solidarity within Ireland, and generated a political consensus that had helped to heal some of the wounds left by a vicious civil war. There was considerable national pride in the skill and determination with which the policy of neutrality had been pursued by the Irish government, as well as great relief that the country had managed to avoid the appalling damage and loss of life that had been inflicted throughout most of Europe. The Emergency had established many areas of shared experience, both ephemeral and profound, with little relevance to those who had served overseas in armed forces. Like many Irishmen who fought for the Allies, my father was broadly in favour of Irish neutrality, only bridling when any defence of that policy was couched in what he considered to be self-righteous ter...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- About the Author

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Suddenly, While Abroad

- 2. The German Raider

- 3. The Irish Legation

- 4. With a Pop Gun

- 5. The Mining Town

- 6. The Abwehr’s Irish Friends

- 7. The SS and Co.

- 8. Speer’s Lethal Fantasy

- 9. Heart of Darkness

- 10. Endgame

- 11. Aftermath

- 12. A State of Denial

- 13. A State of Neutrality

- 14. Radio Waves

- 15. What War?

- 16. Farge

- Appendix

- Notes