- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

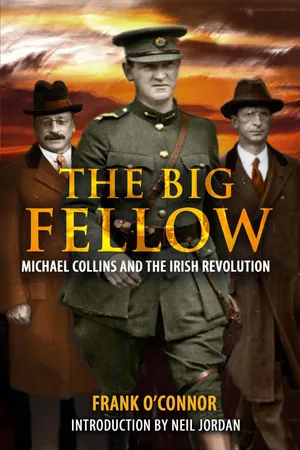

Re-issued with an introduction by Neil Jordan, 'The Big Fellow' is the 1937 biography of the famed Irish leader Michael Collins by acclaimed author Frank O'Connor. It is an uncompromising but humane study of Collins, whose stature and genius O'Connor recognised. A masterly, evocative portrait of one of Ireland's most charismatic figures, 'The Big Fellow' covers the period of Collins' life from the Easter Rising in 1916 to his death in 1922 during the Irish Civil War.

The author, having served with the Anti-Treaty IRA during the Irish Civil War, wrote 'The Big Fellow' as a form of reparation over the guilt he felt with regards to taking up arms against his fellow Irishmen and Collins' untimely death. Liam Neeson has said that he found the book of great assistance when preparing for the role of Collins in the 1996 film directed by Neil Jordan.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Big Fellow: by Frank O'Connor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Lilliput in London

One cold bright morning in the spring of the year of fate, 1916, a young man in a peaked cap and grey suit stood on the deck of a boat returning to Ireland. He was in his middle twenties, tall and splendidly built, with a broad, good-tempered face, brown hair and grey eyes. His eyes were deep-set and wide apart, his nose was long and fine, his mouth well arched, firm, curling easily to scorn or humour. One interested in the study of behaviour would have noted instantly the extreme mobility of feature which indicated unusual nervous energy; the slight swagger and remarkable grace which indicated an equal physical energy; the prominent jowl which underlined the curve of the mouth; the smile which gave place so suddenly to a frown; and that appearance of having just stepped out of a cold bath which distinguished him from his grimy fellow travellers; the uninterested would have passed him as a handsome but otherwise ordinary young Irishman, shopman or clerk, returning from England on holiday.

It was ten years since this young man, Michael Collins, had left his native place in West Cork. A country boy of fifteen, precocious and sturdy, he had taken the train from the little Irish town where for a year he had been put through the mysteries of competitive examination. With his new travelling bag and new suit, which included his first long pants, he had crossed the sea and passed his first night in exile amid the roar of London.

The boat crept closer to the North Wall. He saw the distant mountains heaped above the city, its many spires, its dingy quays. Everywhere the bells were calling to Mass. It might have been the same Dublin of years before, but beneath it was a different Dublin and a different Ireland. Then it had been butter merchants, cattlemen, labourers who chatted with the manly youth with the broad West Cork accent. Now it was soldiers returning on leave from the war, some lying along the benches, their heads thrown to one side, their rifles resting beside them, while others, too excited to rest, paced up and down the deck, glad another crossing was over without sight of the conning tower of a submarine. He chummed up with two of them. Some time soon he felt that, instead of chatting with them, he would be fighting them.

That was the greatest change. Then there had been no talk of fight. Mr Redmond, the leader of the Irish race at home and abroad, hook-nosed, spineless and suave – a perfect Irish gentleman – was in Westminster and all was well with the country. An election was being held in Galway, and there were brass bands and blackthorns, just as in the good old days. There was money to be made, land to be claimed, position to be secured; all Irish nationalism exacted of its servants was an occasional emotional reference to Emmet on the gallows, Tone with his throat cut. Parnell, whose name the lad of fifteen, following his father, had held dear, was dead, and the intellect of Ireland had been driven into the wilderness. The few who could think were asking what was wrong with the country and giving different answers. Some said it had no literature (‘Literature, my bloody eye!’ chorused Lilliput indignantly, busy with increasing its bank balance and saving its soul in the old frenzied Lilliputian way); some that it had lost its native tongue; some that Westminster was corrupting its representatives and that they would be better at home; some that the workers were being exploited by Catholic and Protestant, Englishman and true Gael alike; some that the whole organisation of society was wrong and that it was vain to increase wealth while middlemen seized it all. Against each of these doctrines Lilliput set up a howl of execration, and the intellectuals of one movement were often the Lilliputians of another. So we find the Gaelic Leaguers ranged against the literary men, and the abstentionists against the workers.

That movement of the intelligence, which Lilliput so deeply resented, had taken place because at the end of the preceding century the great Lilliputian illusion had broken down, the belief that one man could restore its freedom to a bookless, backward, superstitious race which had scarcely emerged from the twilight of mythology. It had broken down because the priests had torn Parnell from his eminence and Lilliput had assented. Sick at heart, the sensitive and intelligent asked what it meant. None said ‘Lilliput’, none declared that Ireland was suffering for its sins, or that Lilliput must cast out the slave in its own soul. That is not how masses change. And so arose Yeats and Hyde, Griffith, Larkin and Plunkett.

In turn each of these waves of revolt had spent itself. Synge was dead, Larkin beaten, Griffith a name. The war had brought Lilliput back in strength. There was nothing Lilliput liked better than a good vague cause at the world’s end – about the Austrian succession, the temporal power or the neutrality of Belgium. Given such a cause, involving no searching of the heart, no tragedy, it can almost believe itself human. In proportion to its population Ireland had contributed more to French battlefields than England itself. Lilliput did not mind if Ireland was still unfree. All in good time. The great jellyfish of Westminster, the invertebrate leader with the hooked nose and cold, mindless face, let slip the one great chance of winning freedom. Without firing a shot or sending a man to the gallows he might have had it, but refrained – from delicacy of feeling. Lilliput is nothing if not delicate-minded. And now, let the war end without war in Ireland, and all that ferment of the intelligence would have gone for nothing. So at least the intellectuals thought, though it is doubtful if a historical process once begun ever fails for lack of occasion.

Michael Collins was coming back to take part in a revolution which the intellectuals felt was their last kick. They were gathering in from the wilderness to which the Parnellite disillusionment had driven them: labourers, clerks, teachers, doctors, poets, with their antiquated rifles, their amateurish notions of warfare, their absurd, attractive scruples of conscience.

It must have been thrill enough for the soul of the young man when the ship came to rest and the gangways went down that faraway spring morning. The ten years of exile were over. Sweet, sleepy, dreary, the Dublin quays which would soon echo with the crash of English shells. Even a premonition of what was in store for him could scarcely have stirred him more or the shadow of his own coming greatness; even the feeling that, his work done, the Ireland he loved set free, he himself would personify a mass possession greater even than that Parnell had stood for, and that from his body, struck down in its glory, the intellect of the nation would pass again into the wilderness.

London of pre-war days was a curious training ground for a man who was about to lead a revolution. The Irish in London – except those who stray, who wish to forget their nationality as quickly as possible – stick together, so that, in one sense, London is only Lilliput writ large. One class, one faith, one attitude; the concerts where preposterously garbed females sing sentimental songs to the accompaniment of the harp, boys and girls dance ‘The Walls of Limerick’ and ‘The Waves of Tory’ and play a variety of hurling.

But the young men of Collins’ day, however their instincts might urge them to resurrect Lilliput in London, did not have to do so. If they did not wish to go to Mass, there was no opinion that could make them; if they wanted to read what in the homeland would be called ‘bad books’, there was nobody to stop them. Collins was lucky, not only in being bundled into a big city where he did not need to grow old too soon, but in having a sister who encouraged his studiousness.

To the day of his death he remained an extraordinarily bookish man. History, philosophy, economics, poetry; he read them all and was so quick-witted that he needed no tutor. He went to the theatre week by week, admired Shaw and Barrie, Wilde, Yeats, Colum, Synge; knew by heart vast tracts of ‘The Ballad of Reading Gaol’, ‘The Widow in Bye Street’, Yeats’ poems, and The Playboy.[1] One cannot imagine him doing anything halfheartedly.

Most of the younger Irish, relieved of the necessity for orthodoxy, favoured a mild agnosticism and ‘advanced’ ideas. Collins, who did nothing in moderation, went further: ‘If there is a God, I defy him,’ he declared on one occasion. With great fire and persuasiveness he discussed such ‘advanced’ ideas as the evils of prostitution (which he was shrewd enough to know only at second-hand through the works of Tolstoy and Shaw). Already he was being looked upon as a bit of a character, a playboy, and when in that grand West Cork accent of his he rolled out the Playboy’s superb phrases about his father’s ‘wide and windy acres of rich Munster land’, or of being ‘abroad in Erris when Good Friday’s by, making kisses with our wetted mouths’, of the Lord God envying him and being ‘lonesome in his golden chair’, he was Christy Mahon incarnate, who for the fiftieth time was slaying his horrid da with a great clout that split the old man to the breeches belt.

But the old da refused to die. In fact his life had never been in danger. When members of his hurling club debased themselves by playing rugby, Collins was the hottest advocate of their expulsion. When a poor Irish soldier appeared among the spectators on the hurling field in uniform, Collins drove him off. When Robinson’s Patriots was produced in London, Collins went to hoot it because Robinson dared to suggest that the people of Cork – his Cork – preferred the cinema to a revolutionary meeting.[2] In fact Collins’ studiousness was the mental activity of a highly gifted country lad to whom culture remained a mysterious and all-powerful magic, though not one for everyday use. His reading regularly outdistanced his powers of reflection, and whenever we seek the source of action in him it is always in the world of his childhood that we find it. When excited, he dropped back into the dialect of his West Cork home, as in his dreams he dropped back into the place itself, into memories of its fields, its little whitewashed cottages, Jimmy Santry’s forge and the tales he heard in it. There was rarely a creature so compact of his own childhood. To literature and art the real Michael Collins brings the standards of the country fireside of a winter night, emotion and intimacy, and that boyish enthusiasm which makes magic of old legends and can weep over the sorrowful fate of some obscure blacksmith or farmer. The songs he loved best were old come-all-ye’s of endless length, concerning Granuaile or the Bould Galtee Boy:

Bold and gallant is my name,

My name I will never deny,

For love of my country I’m banished from home,

And they calls me the Bould Galtee Boy.

The student in him found pleasure in Yeats; his turbulent temperament found most satisfaction in songs like this which came out of or went back to the life from which he had sprung; the thing of which he seems to have known nothing and cared less is the great middle-class world of approximations and shadows. His nature safeguarded him from the commonplace. If his pal Joe O’Reilly sang ‘Máire, My Girl’, Collins got up and left the room impatiently. P. S. O’Hegarty quotes one of his later utterances, and one of extraordinary significance. He made it, O’Hegarty says, with a difficulty in finding the appropriate words; which is not to be wondered at, considering that it was his inmost being he was laying bare:

I stand for an Irish civilisation based on the people and embodying and maintaining the things – their habits, ways of thought, customs that make them different – the sort of life I was brought up in … Once, years ago, a crowd of us were going along the Shepherd’s Bush Road when out of a lane came a chap with a donkey – just the sort of donkey and just the sort of cart that they have at home. He came out quite suddenly and abruptly and we all cheered him. Nobody who has not been an exile will understand me, but I stand for that.

There were three qualities which marked Collins all his life long: his humour, his passionate tenderness, his fiery temper – and who shall say it is not an Irish make-up? Strangers usually saw the temper first. He was fond of teasing, was always making a mock of London-born Irish, and on the hurling field his loud voice pealed out in good-humoured gibes of ‘’It it, ’Arry!’ But when he was teased himself he went up in smoke. There is no weakness which men spot sooner or of which they take more advantage. The result was that everyone made a dead set on Collins. It was the same in conversation. When he put his head in everyone turned on him. He was roared down unmercifully, with the inevitable result that he lost his temper. When things developed into a fight he always got the worst of it. The more he tried to assert himself, the more punishment he got. But his tempers never lasted. They blew over in a few minutes, the very worst of them, and then that handsome face of his lit up with the most attractive of smiles; on no occasion does he seem to have borne the least grudge against anyone and what might have been dislike became a good-humoured tolerance. No one could bear malice against a man who bore none, who came up smiling every time and took fresh insults and fresh clips on the jaw with a gorgeous fury which remembered nothing of previous ones.

Collins’ youth, for a novelist, represents the most fascinating part of his life. In this we see the first threshings of his genius in a world which did not recognise it. Something similar occurs in the life of every great man. There is a gruesome period when his daemon compels him to behave like a genius, and the crowd, sensibly refusing to take it on trust, sets upon him. As a boy clerk Collins behaved as though he owned the Post Office. All he demanded of his pals was that they should recognise him as a great leader of men on his own unsupported testimony; they insisted on treating him as no better or wiser or stronger than themselves.

There is always something adorable (afterwards) in the p...

Table of contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Foreword

- Part One: Lilliput in London

- Lilliput in London

- Up the Republic!

- Jailbirds

- Rainbow Chasers

- The First Round

- On the Run

- War

- Part Two: The Body and The Lash

- Spies

- Enter the Black and Tans

- Realists and Dreamers

- Bloody Sunday

- De Valera Returns

- Truce

- Part Three: The Tragic Dilemma

- Treaty

- A Rift in the Lute

- The Great Talk

- Alarms and Excursions

- Civil War

- The Shadow Falls

- Apotheosis

- Endnotes

- About the Author

- About the Publisher