- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In

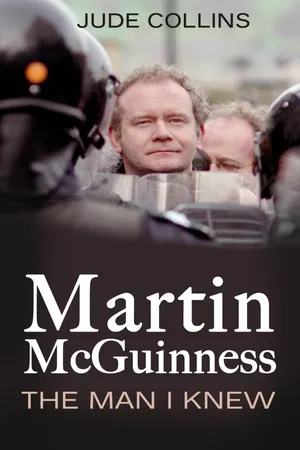

Martin McGuinness, The Man I Knew, Jude Collins offers the reader a range of perspectives on a man who helped shape Ireland's recent history. Those who knew Martin McGuinness during his life talk frankly about him, what he did and said, what sort of man he was. Eileen Paisley speaks of the influence she believes her husband, Ian, had on him; former Assistant Chief Constable Peter Sheridan recounts how the Derry IRA targeted him as a Catholic RUC policeman; peace talks chairman Senator George Mitchell comments on the role he played in talks that led to the Good Friday Agreement; and Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams remembers the man who for so many years was his closest colleague. Other contributors include; Ulster Unionist MLA Michael McGimpsey, prominent Irish-American Niall O'Dowd, peace talks chairman Senator George Mitchell, 54th Comptroller of the State of New York Thomas P. Di Napoli and Presbyterian minister David Lattimer.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Martin McGuinness: by Jude Collins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

5

Dawn Purvis

I can remember Martin McGuinness appearing on TV as part of a Sinn Féin delegation; this was back in the 1980s when their voices were dubbed. He was a scary figure, very much viewed as someone who was instrumental in the IRA’s war and someone who had taken a leading role in that war, thereby viewing all things British – including myself – as dispensable. He was indeed a frightening figure. And the fear was strong. People like my granny would have taken a knife to the TV screen. Working-class unionists would have feared the IRA. If they said something, people in my community would have said, ‘Oh, if they said it, they mean it.’ What I’m getting at is that they were regarded as people who, whatever they said, they followed up on it. So, if there was sabre-rattling, that was believed.

But there came a point where their word was no longer their bond. That was around the time of Castlereagh [in 2002, the heavily fortified Castlereagh police barracks was raided and sensitive intelligence documents were stolen] and Stormontgate [also in 2002, when police raided Stormont amid allegations of an IRA spy ring operating there], and everything that flowed from those events. Things like the claim that Adams was never in the IRA, or that the IRA was never involved in the Northern Bank robbery – all these things were hard to swallow. I think up to that point people would have believed what they said because they followed up on it.

Until the time when Martin McGuinness became deputy first minister, Martin and Gerry Adams were viewed as two sides of the same coin, although Adams was more the bogeyman than McGuinness. I think McGuinness’s admission that he was a member of the IRA gave him some integrity within the unionist community.

In 1992 my home was extensively damaged by an IRA bomb and I remember the anger in the local community. I recall Ian Paisley coming down to the street and getting chased by the local people. I remember Peter Hadden, the Labour representative, coming in and getting chased. I remember the Ulster Unionist Party [UUP] representative, Martin Smyth, coming in and getting chased. They all wanted their photograph taken with this devastation – but where had they been before that?

I wasn’t angry – I was bemused. Why would anybody want to plant a bomb that would have no impact on a police station at all? It wrecked the benefits office and it wrecked our homes. I walked into our house and I could see the sky. I remember thinking, ‘This is a product of the society that we have created.’ I had no hatred for the person who did it. He was as much a product of this society as I was. From that point, I realised that people were products of the circumstances in which they grew up.

Working-class unionist outrage at that time was channelled more towards Gerry Adams than McGuinness. Within loyalist working-class areas, there was a sneaking regard for the IRA and Sinn Féin, a sneaking regard for their inextricable links. It was like the Prods were looking at the Catholics and asking, ‘Why can we not be more like them?’ They seemed a homogenous unit: they had the GAA, they had the Catholic Church – so there was something of a green-eyed monster within unionist working-class areas towards the IRA and Sinn Féin. Even my granny, if she was watching the news and a bomb went off and it was attributed to the IRA, would say, ‘Ah, sure they always get it right.’ But if she heard it was loyalists who were involved, ‘Ah, sure they’d muck it up, they’d muck it up.’ There was a regard for the solidity of the relationship between the IRA and Sinn Féin. And people used to measure that against unionist politicians and loyalists and say, ‘Naw. That doesn’t exist.’ I’m talking here about the 1980s.

In later years, when I was in the Progressive Unionist Party [PUP], there was a much finer analysis of the Provos and their leadership, and what they were trying to do. I sat at many meetings where we unpicked their language and actions to try to work out what they were saying and what they meant. In the early days, there was no analysis of what the republican movement was up to.

***

I remember the first time Sinn Féin came into talks. It was June 1996 and I was in my late twenties. I was petrified. The PUP saw republicans coming into the talks as a good thing. I remember Gusty Spence [a veteran loyalist paramilitary leader] saying, ‘Ah, we need them in, we need them in!’ I was saying to him, ‘Are you mad?’ But Gusty kept saying, ‘We need Sinn Féin in the democratic process. We need them in to see the whites of their eyes and to start working with them.’

I’d seen cardboard cutouts, media caricatures on TV. It was only when they came into the talks – at which point the DUP and Bob McCartney [the then leader of the UK Unionist Party] walked out – that I began seeing members of Sinn Féin as real human beings.

What was perhaps most difficult for me, at first, was that Martin was a purveyor of a mantra that was repeated over and over: about them being the most oppressed people, how this was a war against British colonialism, how we needed the Brits out of Ireland – with no real consideration of this Brit. No real consideration of the unionist community. No real consideration of the impact of IRA violence on the unionist community. That didn’t happen until much later. In fact, there are still those in the republican community who don’t recognise the impact that killing RUC and UDR men had on the psyche of the unionist community.

I met Martin during the peace talks. I was a member of the PUP delegation, and while we didn’t have bilateral meetings with Sinn Féin, you’d see them in the corridor or the dining room, and I have to say, they were very personable, very friendly and genuine. My first face-to-face came as I was walking down the corridor in Stormont – and I was petrified, absolutely petrified. I was on my own and here was this ‘government’ of forty people moving towards me. The Sinn Féin delegation always walked in clumps around the place. I suppose I’d got comfortable because I’d worked in the place and I knew my way about. But now I was going, ‘Oooh ...’, shaking. Do you stop; turn in the other direction; run?

Gerry Adams stopped and said, ‘Hello. How are you doing?’ I was like a rabbit caught in the headlights. I went back to the office: ‘They know me! They know my name! How did they get my name?’ They didn’t offer to shake hands, which in hindsight I thought was actually very big of them. They didn’t want to put me in an uncomfortable position. I remember reflecting on that. I’m a very huggy sort of person and that’s the usual thing I would bounce to do. I remember reflecting on their approach and thinking, ‘Fair play.’

But we were hearing the same rhetoric from Sinn Féin over and over again. The fact is that Sinn Féin never negotiated [in the peace talks leading to the Good Friday Agreement]. In each of the three strands they set down their Éire Nua document and said, ‘This is it. This is our negotiating position.’ And I think it wasn’t until the last forty-eight hours that the serious negotiations got under way. So every time we went into a plenary session, we heard about the discrimination, we heard about the hard time the Catholic community had suffered.

I remember an occasion where Martin himself laughed. The talks had moved to Dublin Castle and he was giving his single transferable speech about being a young man growing up in Derry and not getting a job and so on. And we were all sitting there going, ‘We’ve heard this, we’ve heard this.’ The first time you hear it, OK, but you don’t need to hear it repeated over and over and over again. Hugh Smyth [a senior PUP figure] would sit near the microphone and tear up paper or rattle the coins in his pocket. On this occasion, he interrupted Martin McGuinness’s story. The very patient Senator Mitchell said, ‘Yes, Mr Smyth?’ And Hughie said, ‘I just wish somebody had given him a job all them years ago because then we wouldn’t be listening to this over and over again!’ Martin McGuinness smiled and Adams had to put his head down, and other delegates were going, ‘OK, Hughie, we feel your pain. We know where you’re coming from.’

There was sometimes a sense they were trying to wear us down, a sense of cynicism. Gusty Spence used to say of loyalist communities, ‘Ye’d neither in ye nor on ye, but we were in power.’ He meant you were left in poverty but didn’t dare speak out because unionist leaders would say, ‘You think you’re doing bad? Look at them ones over there!’ It was this notion of ‘Just shut up – youse are doing all right!’

Certainly from people within the PUP, there was a clear recognition of the discrimination that existed towards Catholic communities, but also that it was replicated in some ways in Protestant working-class communities. We always felt that wasn’t recognised within republicanism because it didn’t fit with the narrative they were trying to put forward.

***

I’d say I really only started to get to know Martin McGuinness after the Assembly got up and running in 1998. That year David Ervine and Billy Hutchinson of the PUP were elected to the Assembly and I was the party’s spokesperson on women’s affairs at the time. It was during that time and then after 2007, when David Ervine died and I got elected to the Assembly, that I got to know Martin much better.

I was in the Assembly when Martin was announced as the minister for education, but I was not part of the collective gasp that went up when his name was announced. I was delighted because Sinn Féin was opposed to academic selection and so was I.

From 1998 to 2004, when I worked in the Assembly for the PUP, my boys came in during the school holidays and met whoever was about. They didn’t distinguish between anybody. The year before my youngest son was about to sit the Eleven Plus [an examination taken at age eleven, which decided if a child would attend a grammar or a secondary school], as I was taking the two boys down for their lunch, we met Martin coming slowly up the corridor – he’d broken his leg playing football.

The two boys said, ‘There’s Martin McGuinness!’

So I said to the younger one, Lee, ‘That’s the man who’s in charge of the Eleven Plus.’

Lee said, ‘Can he not do away with it?’

And I said, ‘Why don’t you ask him?’

As Martin came up I said, ‘Good morning, minister. This young son of mine has something to ask you.’

‘Does he? What’s your name?’

‘I’m Lee. I’m supposed to be doing the Eleven Plus.’ Then he said, ‘Would you not do away with the Eleven Plus before I have to do it in November?’

And Martin said, ‘If I can do that, son, I will definitely do it.’

‘Well, do your best,’ Lee told him.

‘Yes, son, I’ll do my very best.’

And he shook hands with both of them.

My two sons were very astute with regard to politics. They watched events on TV and I had them out tramping the streets canvassing from when they were no age. They were watching the talks process and I asked, ‘Who do you think is the best in terms of negotiation?’

The big one said immediately, ‘Seamus Mallon. He’s the best.’

‘What about David Trimble?’

‘Don’t like him.’

Seamus Mallon was a schoolteacher [and deputy leader of the SDLP], whereas David Trimble didn’t have the same nature or personality – he could be quite short, aloof.

After Sinn Féin and the DUP made their big announcement about agreeing to share power in 2007, both parties set up meetings with the rest of the parties in the Assembly to talk about ‘Devolution Day’, which was going to be 8 or 9 May. Sinn Féin still hadn’t worked out that Martin McGuinness was going to be deputy first minister. But we got an official request for a meeting and I said, ‘Yes, absolutely.’ I made the comment David Ervine used to make when Sinn Féin asked for a meeting, ‘Can you send me somebody that hasn’t been in Castlereagh Interrogation Centre and knows how to impart information?’

I met Michelle Gildernew and Martin. It was the first time I’d had a meeting with Sinn Féin and it just felt very informal and comfortable. It was clear talking: ‘Here’s what we’re going to do and this is how we’re going to go forward.’ It was great. We had a series of meetings with Sinn Féin before the PUP got its first meeting ever with the DUP. Up to that the DUP had refused to meet our party. I felt much more comfortable in meetings with Sinn Féin.

During the talks, I don’t think Sinn Féin regarded us as an enemy or a political threat, or in any way chipping aw...

Table of contents

- List of Contributors

- Foreword

- Mitchel McLaughlin

- Peter Sheridan

- Denis Bradley

- Dermot Ahern

- Dawn Purvis

- George Mitchell

- Eamonn McCann

- Danny Morrison

- Jonathan Powell

- Martina Anderson

- John McCallister

- Joe McVeigh

- David Latimer

- Eileen Paisley

- James T. Walsh

- Eamonn MacDermott

- Terry O’Sullivan

- Michael McGimpsey

- Aodhán Mac an tSaoir

- Thomas P. DiNapoli

- Peter King

- Martin Mansergh

- Pat Doherty

- Mary Lou McDonald

- Niall O’Dowd

- Pat McArt

- Bill Clinton

- Gerry Adams

- About the Author

- About the Publisher