- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Renegades: Irish Republican Women 1900-1922

About this book

The history of the Irish republican movement is dominated by the story of the men who took up arms in Ireland's fight for freedom against the British. The names of men like Pearse, Connolly, Collins and Barry still resonate today as heroes who won independence for Ireland. However, the critical role of women in this fight for freedom has often been overlooked. Renegades examines the part played by women in the major political and social revolutions that took place from 1900– 1922. It explores the growing separation of republican women into two distinct groups, those active on the military side in Cumann na mBan and those involved on the political side, particularly with Sinn Féin. It also looks at the often ignored 'war on women', which manifested itself in the form of physical and sexual assaults by both sides during the War of Independence, and the fury of female republicans as the political establishment accepted the Anglo-Irish Treaty. In this evocative account, Renegades restores the women of the republican movement to the prominent place they deserve in Irish history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Renegades: Irish Republican Women 1900-1922 by Ann Matthews in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Irish History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

BUILDING THE FOUNDATION 1865–1900

During the 1890s in Ireland women began to emerge in a significant way in the escalating nationalist movement and by 1921 were accepted as an integral part of republican politics. While these women did break ground with their determination to gain access to public life, they did not instigate the idea of female participation in Irish politics. Rather, they built on the foundation that was created by the Fenian women and the Ladies’ Land League.

Sylke Lehne in her study of the women who formed the Ladies Committee for the Relief of the State Prisoners in October 1865 has presented a sound case, which is that the women who launched this committee set the precedent that the later generation of Irishwomen followed.1 In September 1865, the British government began an offensive against the Fenian movement by raiding the premises of the Fenian newspaper, the Irish People, and arresting the staff. Following this, there were mass arrests and imprisonments of men from different areas of the country. These arrests left many families without an income and subsequently reduced them to destitution. Mary Jane O’Donovan Rossa and Letitia Luby gathered together the female relatives of the prominent Fenians and formed the Ladies Committee for the Relief of the State Prisoners. The women’s first act was to publish an appeal for financial support for the destitute families of the men who had been imprisoned. According to Lehne, both women ‘played a major role in the foundation of the committee while O’Donovan Rossa became secretary of the committee and Luby was the treasurer’.2 The other members of the executive committee were Ellen and Mary O’Leary, Mrs Dowling, Catherine Mulcahy, Isabella Roantree and Jane Stephens.

Mary Jane O’Donovan Rossa (née Irwin) was born in Clonakilty, County Cork, in 1845. She married Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa on 22 October 1864, becoming his third wife. O’Donovan Rossa at this time had five sons by his earlier marriages. Mary Jane ‘gave her services free to the ladies committees until August 1866, when her own circumstances became difficult and she began to draw a salary of £2 a week from the fund’.3 The committee raised money and supported many families and they tried to support the men in prison. This committee very quickly became an integral part of the Fenian movement and it was still collecting funds in the early part of the twentieth century. Sylke Lehne argued that this group of women laid the foundation on which later nationalist and republican women were able to build. She says, ‘the work these women became involved in gave them the self-confidence which became the most important precondition for later women’s movements’.4

The Ladies’ Land League was founded in New York on 15 October 1880 by Fanny and Anna Parnell. The purpose of this committee was to raise money for the Irish National Land League, which had been formed in 1879 to pursue the issue of security of tenure for Irish tenant farmers and of which Charles Stewart Parnell was president. On 31 January 1881, in Dublin, Anna Parnell presided at the inaugural meeting of the Ladies’ Irish National Land League. (Subsequently its name was changed to the Ladies’ Land League.) Katharine Tynan, who was present at the meeting, recalled in her autobiographical work Twenty-Five Years that when she had suggested the organisation be called the Women’s Land League she was told she ‘was being too democratic’.5 Shortly after the Ladies’ Land League was formed, a young woman named Jennie O’Toole visited the office of the league intending to join the committee. She recalled her unease at calling without having a proper introduction, but said that ‘Anna Parnell put her at her ease’.6 She described Anna Parnell ‘as about twenty-seven, of medium height, with thick golden hair, a slender figure and very attractive with a fair complexion and humorous blue eyes’.7 O’Toole became very involved with the Ladies’ Land League and eventually became the secretary.

In October 1881, the leaders of the Land League were imprisoned and the British government officially suppressed the organisation. The women then took over the work of the Land League. They kept a register of land valuations, rents, and the names of the landlords and their agents. They also kept a register of evicted tenants, provided them with relief and enabled the Land League paper United Ireland to remain in publication. The women also organised aid for the prisoners. They set up and funded catering arrangements at jails where the men were incarcerated. However, in the aftermath of the release of the leaders of the Land League in 1882, Charles Stewart Parnell cut off the funds to the Ladies’ Land League to make sure of their compliance, and consequently the organisation was dissolved. The league had lasted just nineteen months, but, in a similar way to the Fenian women, it left a lasting impression on many of the young women who came after.

In July 1883, Jennie O’Toole married John Power and at some point took the name Jennie Wyse Power. She remained a staunch supporter of Parnell, to the extent of naming her son Charles Stewart Wyse Power. In the 1890s she became involved with the Gaelic League.

The Gaelic League, founded in 1893, was a non-political organisation, which aimed to foster the Irish language throughout the country and enable people to rediscover an Irish past. This rediscovery was made possible by the translation of ancient Irish manuscripts. The league used this scholarship to create an interest in the Irish language within disparate sections of the population. A system was set up whereby trained teachers taught classes on a voluntary basis. In 1899, the league appointed its first full-time travelling teacher. These teachers, who were paid £1 a week, travelled throughout the country setting up branches of the league. By 1900, the number of travelling teachers had increased dramatically. A travelling teacher, known as a timire, serviced each newly established branch. They brought learning through Irish to many rural and urban areas of Ireland by setting up classes in primary schools outside official class hours. In these classes they taught Irish dance, history, folklore and music, and they also organised feiseanna, ceilidhe and aeriochtaí. Some children on reaching adulthood ‘joined the social clubs of the Gaelic League’.8

The policy of mixed membership attracted both sexes. Contemporary social life was dictated by the rigid social mores of Victorian respectability and now an alternative social life developed which appealed to many, as young people from a wide spectrum of Irish life were drawn to the classes and the clubs’ social activities. The clubs attracted bishops, priests, students, teachers, civil servants, post office workers, soldiers, policemen, tradesmen and labourers. Under the auspices of the league, dances, poetry readings and musical evenings were held, which evolved into a pleasant social scene. These clubs also became the means whereby both sexes could meet in a respectable setting, and several relationships developed that endured. Áine Ceannt (née Frances O’Brennan), who was born in 1880 in Dublin, joined the Central branch of the Gaelic League as a young girl and recalled ‘engaging in traditional Irish dancing, singing and fiddle playing’.9 She was also an active member of the piper’s band which was attached to the branch. In 1905 she married Éamonn Ceannt, who was a member of the same club. Both signed their names on the marriage register in Irish.10 Eamon de Valera also met his future wife, Sinéad O’Flanagan, at this club.

Society was still largely Victorian in ethos, although this period was one of transition from the rigid rules of Victorian society to the beginning of a modern society where men and women, regardless of their marital status, could mix freely. The old social system did not allow young single women to mix in the company of men without a chaperone. So for many, particularly the middle classes, the Gaelic League functions engendered a form of social revolution. In particular, the membership of the Gaelic League reflected the significant growth of a lower middle class in Ireland.

This development echoes a similar situation in Britain, where developments in technology due to the second Industrial Revolution and the expansion of the British Empire, had enabled a lower middle class to develop exponentially. Between 1850 and 1900 in Britain, ‘the lower middle classes grew from 7 per cent to 20 per cent of the population’ and these changes were reflected in Ireland.11 This came about through the increased need for clerks in banks, railroads and insurance companies. The men who worked in these areas did not wear working clothes and they developed a sense of superiority towards the working classes ‘that gave rise to the expression white collar employees and they were therefore respectable’.12 Due to the growing bureaucracy of the British Empire there was a need for the expansion of the civil service. The need for an educated workforce that would understand the changed industrial technology also led to changes in education. For women, these changes gave them access to clerical positions which had not been available previously, particularly after the invention of the typewriter in the 1880s.

In 1878, the British parliament enacted the Intermediate Education (Ireland) Act, which made provision for scholarships. While this Act made higher education accessible to both sexes, it affected only a very small section of the population. The young women who were able to avail of this education, were already in secondary schools receiving the traditional finishing school education. The new Act encouraged many schools to stream the brighter pupils towards a more academic education. However, the new system did not open doors to education for the majority of children whose parents could not afford to send them to secondary school. Consequently, education remained confined to a relatively small elite from the middle classes in both rural and urban sections of Irish society. In 1884, the first group of nine women received degrees from the Royal University of Ireland. These young women were the first generation to benefit from the new developments. In her work Before the Revolution, Senia Pašeta analysed the level of change wrought in Irish society by the Intermediate Education Act of 1878. She found it had little overall impact on the class structure. By 1911, ‘just six per cent of the school-going population was enrolled at secondary or superior school while the vast majority of children dropped out before completing their final year’.13

The opportunities created by open competition for posts within the civil service had a more significant impact on the lives and ambitions of women and girls from the lower middle classes. New commercial colleges began operating in Dublin, Belfast and Cork. These commercial colleges became training schools for many of the new jobs being created, particularly in the British Post Office. Siobhán Lankford (née Creedon), born in the mid 1890s, was the daughter of a farmer from Clogheen, County Cork. She was a pupil at the Munster Civil Service College on the Grand Parade in Cork city, owned and operated by Philip Murphy, a native of Enniskillen, County Fermanagh.14 In her autobiography, The Hope and the Sadness, Lankford described her fellow students as ‘the sons and daughters of farmers, shopkeepers, civil servants, and the RIC, whose families could afford to pay the fees’ and she also said that she and her fellow students were ‘planning a career in the British Civil Service’.15

In 1912, Siobhán sat an exam for a vacancy in the Mallow Post Office and succeeded in getting the position. This enabled her to work and live at home. Opportunities for young women in the post office became an attractive prospect and these positions became keenly sought after. Figures for Britain show that in 1861, women held just 8 per cent of the jobs in government and the post office. By 1901, this had risen to 50 percent. The situation in Britain was reflected in Ireland.

Developments in vocational education in the 1890s allowed young people from less well-off backgrounds to avail of further education after primary school. In 1898, the Local Government (Ireland) Act created the local authority structure for Ireland. The following year the government enacted the Agricultural and Technical Instruction (Ireland) Act. This Act enabled the Board of Agriculture and Technical Instruction to be created and allowed the county and borough councils in Ireland to levy a rate of one penny in the pound for technical education. The Act also enabled the councils to raise money by borrowing for such schools. Eight municipalities responded to the scheme. By 1902–3, there were twenty-seven county schemes and twenty-four urban schemes in existence.

Technical schools operated a skills-based education system. The demand for this type of education was not as great as that for the more academic system of the secondary schools, so two parallel second level systems developed. According to John Coolahan in his work Irish Education, the reason for this lay in the attitude of middle-class parents towards education:

Irish social attitudes tended to disparage manual and practical type education and aspiring middle-class parents preferred the more prestigious academic-type education, which led to greater opportunities for further education and white-collar employment.16

In the 1890s, a young woman named Mary Colum, who would go on to be one of the founders of Cumann na mBan, observed her uncle making a similar statement. In her memoir, Life and the Dream, Colum recalled his criticism of her because she wanted an academic education:

Over-education in the middle-classes is the curse of the country. The learned professions are crowded, too many doctors and briefless barristers and nobody able to mend a timepiece or make a good suit of clothes.17

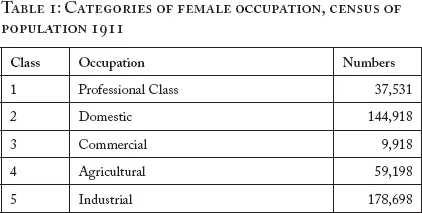

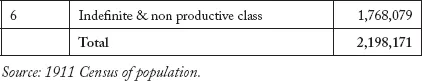

None of these innovations in education had a profound affect on the class barrier. Irish society remained very stratified. The majority of the female population from the urban working class and rural labouring class still finished school at primary level. Many of these young people turned to the technical schools for education. The technical schools provided evening classes to allow early school leavers access to further education. Mona Hearn recorded that at the technical school in Kevin Street in Dublin, ‘four hundred women availed of classes which ranged from shorthand, typing, bookkeeping, French, German, to cookery and dressmaking’.18 The 1911 census shows very clearly the reality of available occupations for the Irish female.

Those women in industrial occupations were urban based and worked in factories, those in domestic occupations were servants, and women in agriculture generally worked as farm servants. The professional classes were divided into four categories: law, medicine, teaching and the arts.19 The women in the first category were barristers, solicitors and clerks of the courts. In the second category were physicians, surgeons, dentists, general practitioners, apothecaries and medical assistants. The third and fourth categories included university professors, teachers, journalists, authors, artists and scientific women.20

The last group, described as an ‘indefinite & non-productive class’, is problematic. In his work, From Public Defiance to Guerrilla Warfare, Joost Augusteijn, when discussing the social background of the rank and file of the IRA, said that ‘the male described in 1911 census as “farmer’s son” was making a statement of social status’.21 The expression ‘farmer’s son’ or ‘farmer’s daughter’ appears to have evolved from the instructions on census forms advising households how to fill in the occupation categories. Farmers were advised to describe their sons and daughters who had finished school and were still living at home (even if they were working on the farms) as ‘farmer’s son’ or ‘farmer’s daughter’.22 This would appear to have been absorbed over time by Irish rural peasant communities as a category of social distinction. For example, a study of the Clonbern parish in Galway in the 1911 census shows the parish had a total population of 2,007, which broke down into 397 individual family units. There were 227 males recorded as farmer’s sons whose ages ranged from thirteen to fifty-four. Thirty-nine females were recorded as farmer’s daughters, who ranged in age from fifteen to seventy-one.23

The instructions for filling in the category for all females living at home, who were not engaged in any work apart from domestic work, directed that it should be left blank. ‘At home’ began to evolve as a term used to describe unmarried women who did not engage in paid work outside the home.

The term ‘at home’ has its origins in the early nineteenth century, when upper-class women had a specific day or evening each week for receiving visitors – this became known as the ‘at home’ day. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the term ‘at home’ was originally used by individuals ‘to indicate the specific day and set time on which they were home to receive callers’. As afternoon tea became fashionable within middle-class circles, a woman in a specific social set had a specific day and time when visitors were received. This information was printed on a carte de visite. Michael Taaffe, who as born in 1898, described this ritual in his autobiography Those days are gone away:

‘At Home’ days played a large part in the social life of the time. In the corner of the lady’s visiting card, the necessary information could always be found engraved in small script. ‘At Home, Second Thursday’ the legend might run, denoting that on the second Thursday of each month tea and cakes would be available to all with whom the hostess had previously exchanged cards.24

By the early twentieth century the term ‘at home’ had expanded to become an all encompassing description, which ranged from the servant girl between jobs, to those from the higher soci...

Table of contents

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- ABBREVIATIONS

- INTRODUCTION

- 1 BUILDING THE FOUNDATION 1865–1900

- 2 CLAIMING THE MANTLE OF THE IRISH JOAN OF ARC

- 3 PROSELYTISM AND NATIONALIST POLITICS

- 4 THE SPIRIT OF REVOLUTION 1914–1916

- 5 REVOLUTION AND REPERCUSSION

- 6 KEEPING THE FLAME ALIVE: THE IRISH NATIONAL AID ASSOCIATION AND VOLUNTEER DEPENDENTS’ FUND

- 7 TAKING A CLAIM IN REPUBLICAN POLITICS 1917

- 8 ATTAINING THEIR ASPIRATION

- 9 WAR 1919–1921

- 10 THE WAR ON WOMEN

- 11 FROM TRIUMPH TO FURY

- 12 FEBRUARY 1922: STRIDING TOWARDS A POLITICAL ABYSS

- APPENDIX

- ENDNOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY