- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

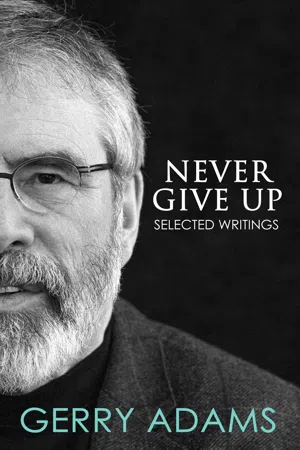

Gerry Adams is known as a man of strong opinions and a quirky sense of humour. Never Give Up is a varied compilation of selected, reworked pieces that Gerry has written since 2009. They cover many issues. Some are fairly serious, others are very serious indeed. A few are whimsical. All will be enjoyed. The book gives an insight into the manoeuvring behind the scenes of political events, and how he became wrapped up in moments of history, both in Ireland and abroad, such as the funerals of Nelson Mandela and Fidel Castro. The book provides an insight into the private life of Ireland's best-known politician, including some very turbulent times in Gerry's life, such as his move from West Belfast to Co. Louth, and his passions, like hiking and the Antrim GAA teams. The book opens with a heartfelt tribute to his close friend and political ally, the late Martin McGuinness.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Friends

and Comrades

Martin McGuinness –

A Life Well Lived

23 March 1917

On Monday 20 March, just after 9.25 a.m., Bernie McGuinness, Martin’s wife, texted me from Altnagelvin Hospital where she had been keeping vigil faithfully during Martin’s stay, to say that he ‘was just the same’.

Later that afternoon, at 2.20 p.m., she texted to say he was very weak. The doctors had just told her and their clann (family) that his organs were failing. She said no one else knew except the family. Her heart was breaking. A short ten hours later, at 12.30 a.m., Martin McGuinness died. His family were with him, except for his son, Emmett Rua, who was on his way back from the USA. I arrived in the hospital shortly after Martin died. Bernie was gracious, as always. She let me sit on my own with him.

Even if I had stayed there all night it would not have been enough time for me to gather myself, to get my emotions in check, to recall all the adventures and difficulties, the losses and gains, the ups and downs, the setbacks and advances that Martin and I had been through together for almost all of our adult lives. So I sat there alone in the hospital ward with my comrade. He was stretched out, calm, peaceful and still in death. Eventually I had to leave. I whispered a prayer and said my farewell.

Ireland lost a hero. Derry lost a son. Sinn Féin lost a leader and I lost a dear friend and a comrade. But Martin’s family has suffered the biggest loss of all. They have lost a loving, caring, dedicated father and grandfather. A brother and an uncle. A husband.

One of the very best things Martin ever did was marry Bernie Canning. One of his very best achievements was the family he and Bernie reared in the Bogside area in the city of Derry. Above all else, Martin loved his family. So our hearts go out to his wife Bernie, to their sons Fiachra and Emmett, their daughters Fionnuala and Gráinne; to Bernie and Martin’s grandchildren: Tiarnan, Oisin, Rossa, Ciana, Cara, Dualta and Sadhbh; to his sister Geraldine, who looked after him in bad times, and his brothers Paul, William, Declan, Tom and John; and to all of the wider McGuinness family.

All of us who knew Martin are proud of his achievements, his humanity and his compassion. He was a formidable person. He did extraordinary things in extraordinary times.

He would not be surprised at the commentary from some quarters about him and his life. He would be the first to say that these people are entitled to their opinions, in particular, those who suffered at the hands of the Irish Republican Army (IRA). But let me take issue with those in the editorial rooms or in the political ivory towers who denounce Martin McGuinness as a terrorist. Mar a dúirt An Piarsach – as Patrick Pearse said – at the grave of another Fenian, O’Donovan Rossa: ‘the fools, the fools, the fools’. Martin cannot answer them back. So let me answer for him.

Martin McGuinness was not a terrorist. Martin McGuinness was a freedom fighter. He was also a political prisoner, a negotiator, a peacemaker and a healer. And while he had a passion for politics, he was not one-dimensional. He had many interests. He was interested in nature. In spirituality. And he was famously, hugely interested in people. He also enjoyed storytelling and he could tell a yarn better than most, including me. In the early weeks of his illness after Christmas I tried to encourage him to write a book, and he was up for that. A book about childhood summers in Donegal, in the Illies, outside Buncrana. About his mother. His memories of his father. His brothers and sister. Schools days and much more. Meeting Bernie. Their courtship. The births of their children. Their grandchildren. But neither of us realised just how terminal his illness was – we knew he was very ill but did not predict this sudden outcome. Unfortunately, he will never write that book. He was a good writer and a decent poet, with a special place in his heart for Seamus Heaney and Patrick Kavanagh.

He loved growing herbs. He thought he was the world’s best chess player. He loved cooking, fly fishing and walking, especially around Grianán Fort in Co. Donegal. He enjoyed watching sports of all kinds. Football, hurling, cricket, golf, rugby. Soccer – he was the world’s worst soccer player. He once broke his leg playing soccer. He had a plaster from his ankle to his hip and he had to go up and down the stairs on his backside. And then two or three days later he discovered that he had also broken his arm – I could never figure that out. His mother Peggy – God rest her – told me that he tripped over the ball. He was great at telling jokes.

He liked all of these activities. But he especially loved spending time with Bernie and their family. That’s what grounded Martin McGuinness.

Martin was a friend to those engaged in the struggle for justice across the globe. And he travelled widely. He promoted the imperative of peacemaking in the Basque country, in Colombia, the Middle East and Iraq. He travelled to South Africa to meet Nelson Mandela and others in the African National Congress (ANC) leadership, as well as in the National Party, to learn from their experiences. The Palestinian ambassador and the ambassador from Cuba attended Martin’s funeral along with dignitaries from Ireland, North and South, the USA, Britain and other parts of the globe. Former American President Bill Clinton gave a wonderful eulogy at the funeral mass.

But Martin was also a man who was in many, many ways very ordinary. He was particularly ordinary in his habits and his personal lifestyle. He wasn’t the slightest bit materialistic. Like many other Derry ‘wans’, Martin grew up in a city in which Catholics were victims of widespread political and economic discrimination. He was born into an Orange state which did not want him or his kind. Poverty was endemic. I remember him telling me that he was surprised to learn that his father, a quiet, modest and church-going man, marched in the civil rights campaign in Derry. The Orange state’s violent suppression of that civil rights campaign, such as with the Battle of the Bogside in August 1969 – a confrontation between the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), supported by a unionist mob, against nationalist Bogside residents, leading to three days of intense rioting – propelled Martin into a life less ordinary.

The aftermath of the Battle of the Bogside saw the erection of barricades and the emergence of ‘Free Derry’, which was made up of the main nationalist estates of the city. From August 1969 until Operation Motorman by the British Army in July 1972, no RUC or British soldiers were able to enter Free Derry. Martin and I first met, forty-five years ago, behind the barricades in Free Derry. We have been friends and comrades ever since. From his time spent on the run, to imprisonment in Mountjoy, in the Curragh, in Portlaoise, in Belfast prison, through his time as the Northern Minister of Education and later Deputy First Minister – alongside Ian Paisley, then Peter Robinson and Arlene Foster – Martin made an unparalleled journey. And reading and watching some of the media reports of his life and death, one could be forgiven for believing that Martin, at some undefined point in his life, had a road to Damascus conversion, that he abandoned his republican principles, that he abandoned his former comrades in the IRA and joined the political establishment. But to suggest this is to miss the truth of his leadership and the essence of his humanity.

There was not a bad Martin McGuinness who went on to become a good Martin McGuinness. There was simply a man, like every other decent man or woman, doing their best in very difficult circumstances. Martin believed in freedom. He believed in equality. He resisted by armed actions those who withheld these rights, and then he helped shape conditions in which it was possible to advocate for these entitlements by unarmed strategies. And throughout it all Martin remained committed to the same ideals that led him to become a republican activist in the first instance.

He believed that the British government’s involvement in Ireland and the partition of our island are the root causes of our difficulties and of our divisions. He was absolutely 150 per cent right about that. The British government has no right to be in Ireland, never had any right to be in Ireland and will never have any right whatsoever to be in Ireland.

Along with others of like mind, he understood the importance of building a popular, democratic, radical republican party across this island. He especially realised that negotiations and politics are another form of struggle. In this way he helped chart a new course, a different strategy. Our political objectives, our republican principles, our ideals did not change. On the contrary, they guided us through every twist and turn and will continue to guide us through every twist and turn of this process.

Thanks to Martin we now live in a very different Ireland, an Ireland which has been utterly changed. We live in a society in transition. The future now can be decided by us. It should never be decided for us. Without Martin there would not have been the type of peace process we’ve had.

Much of the change which we now take for granted – and people sometimes say to me ‘the young ones take it for granted’ and I say to them ‘that’s good, that’s a good thing’ – could not have been achieved without Martin McGuinness.

And in my view the key was in never giving up. That was Martin’s mantra. He was also tough, assertive and unmovable when that was needed. He was even dogmatic at times. Wimps don’t make good negotiators – neither do so-called ‘hard men’. Martin learned the need for flexibility. And his contribution to the evolution of republican thinking was enormous, as was his work in popularising republican ideals.

Over many years there were adventures and craic, and fun and laughs and tears along the way, and both of us realised that advances in struggles require creativity, imagination and a willingness to take the initiative. Martin embraced that challenge. He didn’t just talk about change, he delivered change. He once said: ‘When change begins, and we have the confidence to embrace it as an opportunity and a friend, and show honest and positive leadership, then so much is possible.’

It was a source of great pride for me following the Good Friday Agreement to nominate Martin as the North’s Minister for Education. It was a position he embraced: putting equality and fairness into practice in the Department of Education, by, for example, seeking to end the Eleven Plus – a disreputable exam taken by students in the North at eleven years of age that determined whether a child went to a grammar or secondary or technical school after primary-level education. He sought to improve outcomes for children and to bring about the most radical overhaul of our education system since partition.

In 2007 he became Deputy First Minister and an equal partner to Ian Paisley in government. And they forged a friendship that illustrated to all the progress we have made on the island of Ireland. His reconciliation and his outreach work, and his work on behalf of victims and for peace – in Ireland and internationally – have been widely applauded.

As part of that work, Martin met Queen Elizabeth of England several times. He did so while conscious of the criticism this might provoke. He would be the first to acknowledge that some republicans and nationalists were discommoded at times by his efforts to reach out the hand of friendship. But that is the real test, and if we are to make peace with our ...

Table of contents

- Réamhrá/Foreword

- Friends and Comrades

- Brexit

- The Irish Peace Process

- Irish America

- International

- Collusion and Legacy

- Moving South

- Justice for All

- The Breaking Ball

- The Irish Language

- A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Dáil

- A New Ireland

- Postscript

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Never Give Up: by Gerry Adams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & American Government. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.