- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

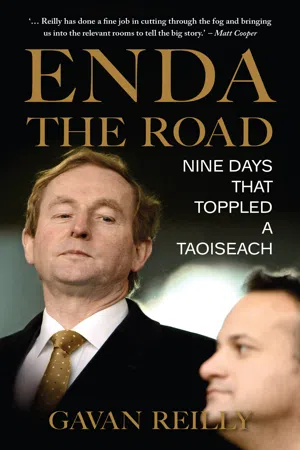

By many measures Enda Kenny was Fine Gael's most successful leader of all time, but his position as Taoiseach was thrown into turmoil in February 2017 by an explosive political scandal – one which threatened to collapse his government, and ultimately cost Kenny his job. In

Enda the Road: Nine Days That Toppled a Taoiseach, Gavan Reilly offers an enthralling blow-by-blow account of the Maurice McCabe scandal: how a Garda whistleblower was targeted by a national smear campaign, and how the government's botched response led to a fatal loss of trust in its leader.

Compiled through exhaustive research and interviews with dozens of key figures and witnesses, Enda the Road is the ultimate account of a nine-day political hurricane whirlwind that brought down a Taoiseach.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Enda the Road by Gavan Reilly in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politica e relazioni internazionali & Politica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

DAY 1

Tuesday, 7 February 2017

It was a chilly morning in Dublin, clear but frosty. It was due to stay dry, but that was the only comfort; Met Éireann’s weather forecast was promising a ‘bitterly cold’ day ahead.

Ministers thumbing through the morning papers would have had plenty to occupy their minds. Many pages were devoted to an RTÉ documentary, broadcast the previous night, about the lives of children waiting to get surgery for scoliosis, a debilitating curvature of the spine. Others outlined a growing class divide in Ireland’s colleges and universities, the prospect of 1.3 million Internet users facing restrictions over illegal downloading, and the arrest of two Irishmen over an alleged gangland hit in the Netherlands.

There were thoughts of matters further afield, too. Northern Ireland had been plunged into a snap election after the resignation of Martin McGuinness as Deputy First Minister, in a row over a so-called ‘cash for ash’ scandal. Arlene Foster had introduced the botched scheme – an incentive to install more sustainable heating systems – while she was enterprise minister, but now refused to stand aside as First Minister while the scheme was investigated through a public inquiry. The ideological gap between green and orange was widening; Sinn Féin was also aggrieved at the DUP’s persistent refusals to entertain issues like gay marriage or an official Irish Language Act. Many feared the next Assembly would face similar trouble.

In London, MPs were debating whether to receive Donald Trump, resident in the White House for only three weeks, as a guest speaker in parliament. It seemed an unwelcome distraction, as in Brussels (and in Dublin) everyone was waiting with bated breath for Theresa May to formally trigger the ‘Article 50’ process, giving two years’ formal notice of the UK’s departure from the European Union. The social protection minister, Leo Varadkar, may have stirred the pot by saying Northern Ireland should be given the option to remain within the EU’s single market, which would further offend the sensibilities of Northern Ireland’s unionist population.

As per usual, Tuesday morning meant an early start for ministers and their closest advisors. The Cabinet was due to meet at its usual time of 9.45 a.m., with the Fine Gael ministers holding their own separate ‘pre-meeting’ at 9 a.m. While the full Cabinet was in session, ministerial advisors would hold their own weekly ‘shadow cabinet’ to brief each other on upcoming developments and policy issues, agree a timetable for announcing their own initiatives, and generally knock heads around the week’s political agenda.

For the Department of Justice it was lining up to be a sensitive and delicate day. Four months previously, Minister Frances Fitzgerald had received two ‘protected disclosures’ – the bureaucratic term for whistleblowing complaints – which, if proven true, would unleash a mammoth scandal within the ranks of An Garda Síochána, Ireland’s national police force.

Ireland’s relatively young whistleblowing law placed strict limits on the degree to which Fitzgerald could share the contents of the complaints. Some details had already made their way into the public domain, though not via the Department of Justice. But after today’s Cabinet meeting, the cat would be out of the bag.

A domino effect would require Fitzgerald to release some of the details of these explosive claims. A State inquiry could not be set up without the approval of both houses of parliament, but neither house could approve an inquiry unless they knew exactly what was being investigated. Fitzgerald and her colleagues would accordingly have to tell the Dáil, and therefore the public, exactly what allegations had been made.

Everyone involved knew this would be a delicate process. Even releasing the allegations into the public domain, without any comment on whether they were true or not, could ruin the chain of command within the Gardaí and make it almost impossible for the force to function. But there was simply no other option: the claims had to be investigated, and that meant announcing them to the world.

Deep down, many ministers had an uneasy feeling in the pits of their stomachs. What is it, they wondered, about Maurice McCabe?

* * *

For a relatively low-ranking member of the force, Maurice McCabe had managed to cast a long shadow across both policing and politics. In the latter end of the previous decade, McCabe – the sergeant-in-charge at Bailieborough Station in Co. Cavan – had raised a series of allegations around maladministration of policing in his Cavan–Monaghan district. The crimes to which he was referring were no minor matter: they included the force’s local handling of a violent offender who had murdered a mother-of-two at a Limerick hotel in December 2007. At the time of the murder, the same man was already on bail twice, for two separate incidents: an assault on a taxi driver in Cavan that April and a violent attempted abduction of a child from her home in Tipperary in October. McCabe felt his Cavan colleagues had not properly prosecuted the first case; if they had, bail would not have been granted after the second and the murder would never have happened.

An internal investigation within the force dismissed McCabe’s allegations, generally upholding the standard of policing in the district. Senior Gardaí distributed a note, to be displayed on the staff noticeboards of each station in the district, clearly stating that the allegations – for which Sergeant Maurice McCabe was named as being specifically responsible – were without foundation.

Around the same time, an allegation of serious wrongdoing emerged against McCabe himself. The daughter of a colleague came forward with a story about a Christmas party in the McCabe family home at Christmas 1998. The girl, who was only six or seven years old at the time, had been playing hide-and-seek with Maurice and some of his children when Maurice found her hiding behind the sitting-room sofa. At the time the girl – known only as ‘Ms D’ – believed McCabe had simply tickled her, but by 2006 the now fourteen-year-old was interpreting the incident in a different light. Distressed, she went to her parents and told them that the encounter involved ‘dry humping’. Her parents duly referred it to the Gardaí. (As it happened, this allegation resurfaced not long after the girl’s father had been disciplined within the force after McCabe complained about him attending the scene of a suicide while drunk and off duty.)

McCabe told the investigating Gardaí he completely rejected Ms D’s allegation, insisting he knew nothing about it, that this was the first he had heard of it, and rejecting vigorously any suggestion that he had acted in any way inappropriately. Ms D’s allegation was eventually brought to the Director of Public Prosecutions, James Hamilton, who found no grounds for action: it was simply one person’s word against another, and even if the claim could be substantiated, there was no evidence of a crime being committed. The allegation appeared to dissolve away.

By late 2012 McCabe was once again on the radar of Garda HQ. He had become aware of suspicious behaviour in how motorists’ penalty points were being quashed, citing examples of public figures, sportsmen and celebrities who had had penalty points removed from their licences. While it was always possible to have points quashed, motorists were supposed to make a compelling case to someone of inspector rank or higher – arguing that there was a fair and legitimate reason why the points should not be applied, or why the corresponding fine should be waived. McCabe suspected that not every cancellation was legitimate; some private vehicles had points cancelled up to seven times. Some beneficiaries named under Dáil privilege included journalist and broadcaster Paul Williams, District Court Judge Mary Devins, and Ireland’s leading all-time rugby union points scorer Ronan O’Gara.

Hoping the full depth of the scandal could be exposed, McCabe and fellow whistleblower John Wilson began sending examples to individual TDs – including members of the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) – and to the Comptroller and Auditor General, the official public auditor. The PAC decided the matter justified further investigation and so asked the Garda Commissioner Martin Callinan to give evidence. It even considered inviting oral evidence from McCabe himself.

This put Callinan on a collision course with both McCabe and the PAC. He insisted McCabe had illegally shared records from the Garda PULSE computer system without authorisation and that the PAC had an obligation to return the documents under data protection law. A tug-of-war followed, leading to McCabe giving evidence in private, behind closed doors, and Callinan giving five hours of evidence in which he referred to the actions of McCabe and Wilson as ‘quite disgusting’.

But again, just as McCabe was becoming a problem for Garda headquarters, the previous allegation arose once more. Whispers began to circulate in media and political circles that perhaps McCabe was not to be trusted – that this man was not so perfectly motivated. There was a suggestion that McCabe had an allegation of sexual assault on his record, against a minor, and that anything he said now would have to be taken with a pinch of salt.

Those whispers appeared to stop when Martin Callinan suddenly resigned in March 2014. The Commissioner was already under huge political pressure for his seemingly insensitive and brazen handling of the McCabe allegations regarding the ticket cancellations, especially when the transport minister Leo Varadkar – who had become aware of the allegations via the Road Safety Authority, and who shared the concerns about the points system being abused – described the actions of the whistleblowers as ‘distinguished’, as opposed to ‘disgusting’. Once a separate scandal arose, of illegal tape recordings of phone calls at Garda stations, Enda Kenny communicated his disgust and Callinan ‘retired’ abruptly on 25 March.

He was replaced – first on an interim basis, but then permanently – by Nóirín O’Sullivan, his Deputy Commissioner, who had occupied the office next to his own and who had sat beside him during his five-hour grilling at Leinster House. Despite her ties to her predecessor, O’Sullivan insisted she wished to make An Garda Síochána a warm and welcoming environment for whistleblowers, whose bona fides could not be challenged and whose allegations deserved full scrutiny.

* * *

Barely two months after Callinan’s departure, another head would roll. Within weeks of appearing before the PAC – behind closed doors, but in full Garda uniform – McCabe revived his 2008 allegations of wrongful policing in Cavan–Monaghan, handing over a dossier of his claims to the Fianna Fáil leader Micheál Martin. Martin in turn raised the issue in the Dáil and passed the claims on to Enda Kenny, who commissioned a report from barrister Seán Guerin.

One of McCabe’s complaints dealt with the former Commissioner himself, on the premise that Martin Callinan had made a ‘serious error of judgement’ by considering the Cavan–Monaghan district officer for promotion when there were serious concerns around policing in his area. As there is no internal manager for the Commissioner to answer to, any complaints against them are passed to the Minister for Justice. McCabe’s complaint about Callinan was therefore referred to then-Minister Alan Shatter.

Guerin’s subsequent assessment was that Shatter had mishandled some of McCabe’s allegations – including the complaint against Callinan, by immediately sending it back to Callinan himself for investigation....

Table of contents

- Praise for Enda the Road

- Author’s Note

- PROLOGUE

- DAY 1

- DAY 2

- DAY 3

- DAY 4

- DAY 5

- DAY 6

- DAY 7

- DAY 8

- DAY 9

- AFTERMATH

- Note on Sources

- Acknowledgements