![]()

![]()

2

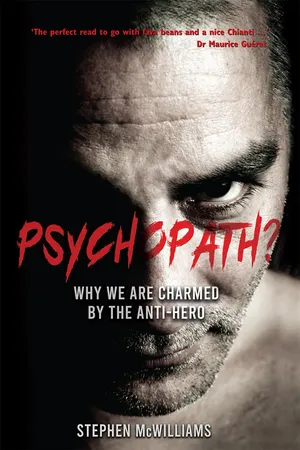

The Fictional Psychopath

‘Everybody lies.’

– Gregory House MD1

Psychopaths are essential in fiction. From a writer’s perspective, they tend to exist within the plot to present a challenge for the hero, who, of course, we usually admire. Most fictional psychopaths are deliberately unlikeable, even if the overall effect is sometimes absurdly comical. Think of all those James Bond villains parodied by Mike Myers in his Austin Powers films. Others are simply repulsive without the humour. But often enough it is the protagonist himself who is psychopathic. Such an anti-hero needs to be charismatic if we as readers (or viewers) are to remain interested in his overcoming whatever challenge the plot throws at him. The likeable fictional psychopath is what this book is all about: the despicable anti-hero whom we admire despite ourselves.

This list has been carefully chosen. Novels are the best source, especially where they are part of a series that allows for the gradual development of a character over time. This gives us plenty of backstory, telling us a great deal about the fictional psychopath’s biographical misadventures. Television shows that run for several seasons do likewise, as they often incorporate flashbacks or other techniques that provide background information on the anti-hero. Films are a little more difficult, given that they are rarely more than two hours in length. As they usually contain insufficient detail in their own right for our purposes, they have only been included where they represent adaptations of existing novels.

The term ‘psychopath’ should not be used lightly. Many fictional anti-heroes are not psychopaths. Some are sociopaths, some have antisocial personality disorders and others are not on the spectrum at all. Most importantly, opinions may differ and thus we need an objective method of deciding whether or not our fictional anti-heroes are true psychopaths before we bother discussing them any further. The Psychopathy Checklist, devised by Canadian psychologist Robert D. Hare and referred to in Chapter 1, is considered the gold standard in deciphering psychopathy, provided it is used properly by an expert who thoroughly interviews and investigates the individual.2

In real life, an index event (the crime that led to the forensic assessment) is not enough evidence upon which to base an opinion. Indeed, a competent assessor will often exclude the index event and instead focus on the individual’s case history. In this book, we do not always have that luxury. As a good plot is often driven by a series of index events, the latter may comprise much of the information we have about the anti-hero. Where backstories are provided, key gaps may exist, and obviously we are not in a position to interview fictional characters to fill in these gaps. As a result, some artistic licence is necessary when applying the Psychopathy Checklist to a fictional character, which hopefully the reader will forgive. To compensate for missing information, we will generally allow ourselves the research cut-off score of twenty-five.

The traits in the Psychopathy Checklist are divided into four domains.3 Interpersonal traits govern how the psychopath makes himself appear to others; affective traits relate to how the psychopath feels (or rather does not feel) on an emotional level; lifestyle traits pertain to the manner in which the psychopath interacts with society (see endnote 5, p. 271, on the two sexual traits); and antisocial traits are those that lead to behaviours that society deems to be unacceptable (those traits that will get you arrested). The specifics of the traits are as follows:

Interpersonal Traits

1. Glibness/Superficial charm

2. Grandiose sense of self-worth

3. Pathological lying (lying relentlessly, even when it is not necessary)

4. Manipulation for personal gain (this often involves ‘impression management’)4

Affective Traits

5. Shallow affect (an impaired ability to feel emotion even if one can mimic how it looks to feel it)

6. Callousness or lack of empathy

7. Lack of remorse or guilt

8. Failure to accept responsibility for one’s own actions (a tendency to blame others instead)

Lifestyle Traits

9. Parasitic lifestyle (taking advantage of the kindness or vulnerability of others)

10. Impulsivity (acting suddenly without weighing up the risks and benefits)

11. Lack of realistic long-term goals (making plans far beyond one’s obvious capabilities)

12. Need for stimulation or excitement

13. Irresponsibility (failing to live up to one’s obligations or commitments)

14. Promiscuous sexual behaviour5

15. Many short-term (marital) relationships (or unstable interpersonal relationships in the youth version of the Psychopathy Checklist)

Antisocial Traits

16. Poor behavioural controls

17. Early behavioural problems

18. Juvenile delinquency

19. Criminal versatility (engaging in a variety of crimes instead of specialising in one)

20. Revocation of conditional release, such as parole violation

To complicate matters, there may be more than one subtype of psychopath. Some experts assert that there are really three, namely the classic psychopath, the manipulative psychopath and the macho psychopath.6 All three subtypes score highly in the affective traits listed above, while the classic psychopath scores highly in all four categories of traits. The manipulative psychopath scores highly in the affective and interpersonal traits but scores relatively less in the lifestyle and antisocial traits. In essence, such an individual is more likely to be a charming confidence trickster than a demonstrative risk-taker or menacing bully. The macho psychopath scores highly in the affective, lifestyle and antisocial traits but scores relatively less in the interpersonal traits. Such an individual is more likely to be a demonstrative risk-taker or menacing bully than a charming confidence trickster. While the manipulative psychopath will charm you out of your life savings, the macho psychopath will put you in hospital. The classic psychopath could possibly do both.7

The above is all very well in real life, but in fiction the reader (or viewer) usually possesses a level of omniscience that bestows some immunity to the impression management of a psychopath. Surely, we readers can see past their games? Therefore, how could a fictional psychopath possibly be likeable? Before we embark on the actual reasons, it is important to remember that the average reader and viewer will usually only finish a book or film if they have some affinity for (or at least fascination with) one of the main protagonists. When the latter happens to be a psychopath, it is especially important to the author or director that we like the protagonist sufficiently to persist with the story. So, perhaps the most fundamental reason the fictional psychopath is likeable is that he simply must be so for his very survival as a fictional entity.

The real question we should be asking, however, is how the author or director achieves the anti-hero’s likeability notwithstanding their nefarious deeds. There are at least ten possible reasons outlined below. Of course, these reasons might be applied to anyone and not just fictional psychopaths, but they are particularly necessary for the latter, given that we also have a host of reasons not to like them.

The first reason we like a fictional psychopath (or a real one, for that matter) is their calmness and courage under fire. Surgeons and firefighters save lives. CEOs and politicians lead the masses. Kevin Dutton, professor of experimental psychology at Oxford University, holds that society needs its psychopaths precisely because these individuals do not scare easily; instead they relish the chal...