eBook - ePub

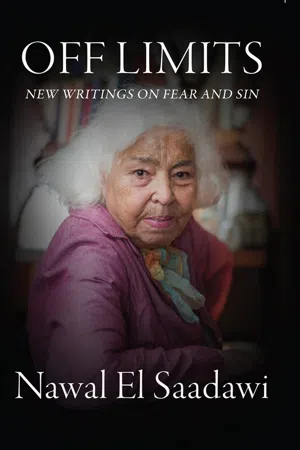

Off Limits

New Writings on Fear and Sin

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Nawal El Saadawi is a significant and broadly influential feminist writer, activist, physician, and psychiatrist. Born in 1931 in Egypt, her writings focus on women in Islam. Well beyond the Arab world, from Woman at Point Zero to The Fall of the Imam and her prison memoirs, El Saadawi's fiction and nonfiction works have earned her a reputation as an author who has provided a powerful voice in feminist debates centering on the Middle East.

Off Limits presents a selection of El Saadawi's most recent recollections and reflections in which she considers the role of women in Egyptian and wider Islamic society, the inextricability of imperialism from patriarchy, and the meeting points of East and West. These thoughtful and wide-reaching pieces leave no stone unturned and no view unchallenged, and the essays collected here offer further insight into this profound author's ideas about women, society, religion, and national identity.

Off Limits presents a selection of El Saadawi's most recent recollections and reflections in which she considers the role of women in Egyptian and wider Islamic society, the inextricability of imperialism from patriarchy, and the meeting points of East and West. These thoughtful and wide-reaching pieces leave no stone unturned and no view unchallenged, and the essays collected here offer further insight into this profound author's ideas about women, society, religion, and national identity.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Off Limits by Nawal El Saadawi,Nawal El Saadawi, Nariman Youssef in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Middle Eastern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

A Study of Philosophy and

Change

(from Nawal El Saadawi’s notes)

Philosophy is not a mental sport that is only practised inside the head and deals with abstract theories, away from the ever-changing cycles of life. It is not separate from quotidian socio-political life, whether public or private, and it is connected to other branches of knowledge, like medicine, physics, mathematics, psychology, history and religion.

Specialisation is often responsible for separating philosophy from the rest of life. Systems of education, since knowledge was turned into sin, have been designed to obscure knowledge rather than reveal it, to muddle the mind and promote blind obedience for the powers that be, whether at state or family level, in heaven or on earth.

I’ve found pleasure in thinking since I was a child. I used to think about questions that occupy most children’s minds, for instance: ‘Who created the stars in the sky?’ The answer was always the same: ‘God.’ Then came the next natural question: ‘Who created God?’

The concept of ‘godhood’ confounds children like it does philosophers. When it comes to delving into so-called taboos or subjects held sacred, the minds of children sometime dare to tread where philosophers’ don’t. Philosophers are aware of the risks of imprisonment or exile, should they challenge political or religious authorities. Children have to be indoctrinated into that awareness at home and at school.

The meaning of the word ‘Allah’ changed according to the views of the people around me. My peasant grandmother used to say in her simple dialect, ‘God is just and known to be reasonable.’ My uncle the Azhar scholar used to say that the human mind is not equipped to really know God or understand his wisdom in creating injustice and evil. But my childish mind never accepted injustice. Not since the first time I experienced it, when I saw my father favour my brother just because he was a boy. I was better in school and more intelligent, so why was I treated as an inferior?

I learned from the teacher at school that God, according to grammar rules, was masculine and not feminine, and that God’s book, the qur’an, addressed males only, and that a man has double a woman’s share in inheritance. When I wrote my mother’s name on my copybook alongside my father’s, the teacher crossed it out and told me off, ‘Your surname is only your father’s name!’ I felt that was unfair to my mother. It was her, after all, who cared for me more than my father did.

I saw injustice around me in the lives of poverty-stricken peasant women and men in my family and my sad village in the middle of the Nile’s delta. I asked: ‘Where does poverty come from?’ And the answer came: ‘God creates some people rich and others poor. Everyone’s degree of wealth is determined by Allah.’

My childish mind never accepted that injustice that was attributed to God. I thought, like my grandma said, that God was just and known to be reasonable. My brain never stopped asking the childish question, which occurs instinctively to all children at some point: ‘Why would God be unfair to the poor, and to women, including my mother and me and my sisters?’

Oneness

In childhood, people experience the natural oneness between body, mind, soul, the universe and other people around them. That was also the nature of early life in old pre-slavery human civilisations. Human societies, in their childhood, were not savage nor built on war and murder and rape as most historians have imagined. Old civilisations – in Egypt, Babylonia, Persia, India, China, among others – had philosophies that were based on such unity; the unity of all existence with all its living beings including humans. And human beings were not comprised of just mankind, but mankind and womankind. Gods too were female and male. The primary goddess was Mother Nature.

Then came the fascination with socio-political developments that led to the advent of an ethos of slavery, dividing the universe into heaven and earth, and humans into body and soul, and society into masters and slaves. Women were joined to the ranks of slaves. All of this happened gradually. When the social order transformed from matriarchal to patriarchal in Ancient Egypt, for instance, the mother didn’t immediately lose her position in religious and political life. That only happened after the patriarchal order had stabilised, with one heavenly God becoming the male father of the whole of humanity. Following that, Adam became the single origin of humans, and Eve merely a subsidiary being branching out from his ‘crooked rib’. In other words, it was as if the female was birthed from the male and not the other way around. In Arabic, humanity is referred to as banu Adam, ‘the sons of Adam’, and not the sons and daughters of Adam and Eve. In the Old Testament, Eve merely features as the origin of sin and evil and disobedience, because she reached with her hand – and her mind – for the tree of knowledge. In the qur’an, Eve’s name doesn’t feature at all. She is only mentioned as Adam’s wife, and both of them – in the dual form – are said to have eaten from the tree (without naming the tree). But, it’s Adam alone – in the singular form – who received the word from God and was pardoned. He alone – in the singular form – is also taught the names of all things.

With the establishment of a slavery order came changes in philosophy, language, religion, politics, and ethics that turned maleness into the accepted standard. A new order based on gendered division of labour assigned physical, bodily work to women (and slaves), considering them to be bodies with no mind, while intellectual work (philosophy) became the domain of (upper-class) men. Except that for a while in Ancient Egypt, Nut remained the goddess of the sky, while her consort Geb was the god of the earth. Daughters inherited the throne through their mothers, and the old trinity consisted of the mother, the daughter, the father. With the changes that society underwent, the father moved gradually from his position as the god of the earth to the one God up in heaven, while the mother descended from her seat to become a symbol of land and fertility. The trinity changed to: the father, the son, the holy spirit – where the holy spirit supplanted the mother who had lost her name, and became identifiable only by her husband or male son.

The early natural matriarchal philosophy was built on the holistic unity of life, on collaboration and justice and mercy and love. With the emergence of the slavery order came philosophies of power, and the power of a ruling father God who derives authority from the sacredness of his divinity and not from justice and mercy. The goddess Nut resisted that ethos when in 4988 BCE, Old Egypt, she told her daughter Isis: ‘I do not advise my daughter who will inherit my throne to draw her authority from divine sanctity. I advise her instead to be wise, merciful, and just.’

The tenet of justice and mercy was still resisting the rising tide of the tenet of power based on accumulation of money and absolute male authority in governance and at home. Another example of the tenet of justice and mercy is the following maxim from Ptahhotep: ‘Live in the house of kindliness, and fill your heart with mercy before filling your case with gold.’ Isis was a symbol of wisdom and her sister Maat a symbol of justice. Isis was the goddess of life and light (and also knowledge) and she was depicted with a sun ring above her head. But with the transition into the system of absolute patriarchal authority, her consort Osiris was accorded wisdom, and his son Horus inherited the throne which no longer passed from mother to daughter.

Rereading history in the light of new progresses made in archaeology unmasks these old narratives and thereby reveals the truth.

Philosophy in Ancient Egypt

The word ‘philosophy’ is derived from the Greek root ‘philo + sophia’ meaning love of wisdom. Hypatia is an example of a female thinker and philosopher who was killed in Alexandria, Egypt, in the name of religion.

The philosophy of slavery started in Ancient Egypt with the idea of one father from whom everything descended and his son as the heir. Osiris became the heavenly god who leads the battle between good and evil, followed by his son Horus who fought against Set, the god of chaos, who had killed Osiris. Ipuwer, author of the Ipuwer Papyrus, was perhaps the first sociologist in Ancient Egypt. He raged against the slavery mentality, looked for the heavenly god in vain and prophesised the coming of a saviour.

The souls of the dead are supposed to recite from the Book of the Dead on the day of resurrection. As proof of no wrongdoing and of having followed the commands of the pharaoh god, ruler in heaven and on earth, the dead recite: ‘Glory be to you, great god of truth and justice. I have not sinned. I have done no evil. I have not reduced the measuring vessel or added to the pan of the scales. I am pure, pure.’

Akhenaten and Nefertiti were inspired by the Book of the Dead, developed in Thebes, but they only took from it the tenets on integrity in dealing with others. Perhaps because they worked under the guidance of Akhenaten’s mother Tiye, they left out the tyrannical patriarchal parts. The two of them, together with Tiye, started a political, religious, ethical and social revolution in Egypt, in an attempt to re-establish the old values of justice and mercy and oneness and humanity. Akhenaten was depicted with a body more female than male, and as a just human god whose sky oversaw the earth with a maternal tenderness, and whose sun brought the light of truth and knowledge, which was the same image associated with Isis who carried the sun ring above her head and indiscriminately spread the light of wisdom and knowledge. The worship of multiple – male and female – deities never caused the sun to withhold its light. All humans were equal under the sun.

The hymns of Isis and Osiris, and of Akhenaten and Nefertiti (and Tiye), were directed at the goddess of wisdom, like the following hymn from the time of Isis:

O Isis, light-giver,

Grower of crops in the land,

Who brings forth life from her womb,

Like a hatchling from a bird’s egg,

O mother of all life,

Life of the world,

Supreme mother of the universe.

Grower of crops in the land,

Who brings forth life from her womb,

Like a hatchling from a bird’s egg,

O mother of all life,

Life of the world,

Supreme mother of the universe.

With the transition to the patriarchal order, hymns like this changed. The labour of Tiye the mother and Nefertiti the wife was erased from history, and philosophy and knowledge and hymns were appropriated for Akhenaten alone.

Some believe Moses took certain Akhenaten hymns and made them the basis of his tenets for Judaism. In the Old Testament, the name of Eve shares the same root as the word for ‘life’, and her fall from grace ensures that the new paternal god has no competition in the form of maternal life. The concept of one heavenly god was taken from Akhenaton, who said, ‘The Nile in heaven gives living water to strangers in all the lands.’ And, ‘Aten (sun god) lives in the hearts of humans.’ It was also Akhenaten who ordered the destruction of the idols of previous gods and closed their temples, then abandoned wicked and unjust Thebes to build a new capital at Amarna dedicated to the worship of Aten. Isn’t this what political change looks like whenever a new prophet or king or president comes along with new ideas?

But when conflict between the new king and the priests of past kings broke out and left Akhenaten and Nefertiti defeated, the new rulers destroyed their statues and left no trace of them.

Persian philosophy

Zoroaster inherited the conflict between body and soul, and between good and evil. Philosophy was separated from politics and disassociated itself from social movements that resisted the tenets of slavery. The king of kings in Persia was an unjust tyrant like the pharaoh in Egypt. His eyes and spies were everywhere, reporting back the sentiments hidden in the hearts of his subjects.

The king once killed a young man with an arrow then asked the victim’s father what he thought. The slave father prostrated himself on the ground, rubbed his forehead in the dust between the king’s feet and said, ‘There’s no wisdom beyond your wisdom and no shot more accurate than that of your blessed hand, divine King of Kings!’ The king had intended to kill him too for bringing a dissident son into the world, but he pardoned him when he found him to be a true believer.

The crime of disbelieving or not accepting the wisdom of the god-king was punishable by death. This ‘crime’ has existed since the start of the age of slavery and still exists today in many parts of the world, East and West. It has been instrumental throughout history in separating philosophy from religion and freezing intellectual thought, old and contemporary, inside fixed repetitive moulds that renew and bolster whatever belief happens to prevail in a given society and the religion of the state as stipulated in the constitution. Even when the constitution stipulates nothing of the sort, and even where church and state have been separated, the charge of blasphemy or atheism or dissent against the accepted authority has continued to intimidate philosophers and scholars through the ages, all the way up to the present.

Maternal care and philosophy

Divine miracles that foretell the birth of a prophet or philosopher or spiritual leader abound. In Persia, for instance, there were stories predicting the appearance of Zoroaster before he was born: ‘The God of light heard the complaints of his people and send them a prophet whose strength would be their salvation.’

There was also the myth about how Zoroaster’s mind was embodied in his mother, a noblewoman who appeared to him in flashes of lightning. From her he received his calling in life: To bring light to the children of darkness.

Similar myths have recurred in the biographies of most prophets: The mother-figure is the one who guides her prophet son toward wisdom. Many prophets and philosophers had no fathers, or at least not ones we hear about. Their wisdom is received from the mother, and it is she who saves them from the tyranny of the ruling powers. Moses was saved from being murdered by the pharaoh by his mother, Jesus was protected by his mother, and Muhammad was protected by Khadija from the wrath of the quraysh.

When Zoroaster was born, he came to the world laughing, driving away the spirits of evil who had surrounded his mother. The whole of nature rejoiced in light, the wind and the rivers and the trees chanted the uniting mantra. The newborn’s mother fed him with courage and wisdom, mercy and love of justice.

And when the mother of Prophet Muhammad predicted she was pregnant, she knew she was carrying a prophet because she saw the light. There was light everywhere. She went home shaking and crying: ‘Cover me! Cover me!’ And later, it was Khadija who was there to support the prophet, calming him then telling him to get up and go spread God’s message.

Evil spirits would have killed Zoroaster if it weren’t for his mother’s strength and protection. Jesus’s enemies would have killed him if it weren’t for his mother, Maryam. And Khadija, the mother figure who was twenty years Muhammad’s senior, was a rich and well-connected noblewoman who protected him from those among the quraysh who would have harmed him.

Without the care of women and mothers, most prophets and philosophers would have perished. Mothers played an important role in developing the values of justice and mercy in the hearts and minds of those prophets and philosophers who all, across the different religions, had a shared dream: For justice to prevail over tyranny, to unite humanity under conditions of freedom and love, and to bring an end to inequality. Their symbol for this human and universal oneness was the name of God, the supreme conscience. Unfortunately, it is injustice, war, and slavery that prevail to this day and take on a variety of forms.

When Zoroaster asked himself, ‘What is God’s purpose behind the existence of evil, injustice, and war?’, he started to doubt God’s wisdom and justice, and even existence. His quest for God as oneness is represented in the texts that now make part of the Zoroastrian book, Avesta, where God is manifested in social justice, collaboration, equality, love and fraternity. ‘If you know truth, you know God. God is justice,’ says Zoroaster. Which is the same definition I heard from my peasant grandmother when I was six years old: ‘God is just and known to be reasonable.’

Philosophers in Ancient Greece and in the modern West were influenced by the old philosophies of Egypt, Persia, India and China – just like the prophets befor...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Content

- Publisher’s Note

- Gravity and the Forbidden Apple

- The Most Pious Men in the World

- How Far from My Parents Have We Come?

- A Sweet Murderous Woman

- My Life’s Companion

- My Cousin Naima’s Son

- No Virtue Without Freedom

- A Letter from a Woman Prisoner

- The Girl Outside the Court

- A Girl’s Death

- Can We Not Even Wonder?

- Not an Ideal Woman

- Religion, Women and Cinema

- Absolute Certainty and the Virus of Doubt

- Taleq, Professor!

- Hercules and Antaeus

- Defamation of Religion and Al-Gama‘a in Ramadan

- Reading Patriarchy in Egyptian History

- Psychiatry and Atheism

- Economics, Sex and Personal Status Law

- How Costly is the Service of Religion?

- Memories in the Mother Tongue

- No Objectivity in a Violent World

- Equality in Oppression

- Political Islam

- Between Two Seas

- When Does the Fall Begin?

- With Knowledge Comes Pleasure

- The Price of Writing

- An Old Friend

- Nour’s Buried Memories

- A Study of Philosophy and Change