- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

On 9 November 1918 Ebert became Imperial Chancellor as revolution broke out in Berlin. He opposed the radical left, declaring, 'Without democracy there is no freedom. Violence, no matter who is using it, is always reactionary', but he compromised Weimar democracy by his dependence on the army command and his use of the para-military Freikorps against the left. Ebert headed a joint SPD-USPD government until elections were held to a National Constituent Assembly in January 1919. Ebert became president of the new Weimar Republic (Germany's first democratically elected head of state) and retained office in a turbulent period in German politics. There were arguments among the Allies over how Germany should be treated, as France, Britain and the United States prioritised different objectives. In May 1919, the terms of the Treaty - on reparations, war guilt clause, loss of territories in Europe and colonies, limitations on armed forces - were presented to German representatives, precipitating opposition in government and the Armed Forces, and heated discussion in Cabinet. He continued as President until 1925, forced to confront the issues that arose from the Treaty and its political and economic consequences. After his death came the unravelling of the Treaty and the book examines how much of a part it played in creating the circumstances of the Second World War.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

I

The Life and the Land

1

The Party Man, 1871–1913

Friedrich Ebert’s life was entwined with the birth and the death of the German Empire. On 18 January 1871 Wilhelm I of Prussia was proclaimed German Emperor in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles in a ceremony intended to humiliate a France recently defeated in war. On 4 February 1871 Ebert was born in Heidelberg into a tradesman’s family. At the age of 48, he succeeded the last Hohenzollern Emperor, Wilhelm II, as the head of the German state, the first commoner to hold that position. Ebert’s father, Karl, was a master tailor, successful, relatively prosperous, a Roman Catholic with socialist sympathies. His mother, Katharina, was a Protestant and bore nine children, of which Ebert was the seventh. The writer Mark Twain, visiting Heidelberg during Ebert’s boyhood, described in A Tramp Abroad the beauty of the town, perched on the river Necker, dominated by a picturesque ruined castle, students from Europe and America thronging the ancient university.

Ebert had an elementary education, leaving his Catholic school at 14, but showed some academic potential. A local priest tried to persuade the family to put him forward for the church, opening the opportunity to more advanced education. Ebert may have argued that he lacked spiritual devotion, though he retained a lifelong sympathy for Catholicism despite the free-thinking nature of the party in which he made his career. He became an apprentice saddle maker in 1885 and completed his induction into the leather-working trade – based in small workshops rather than the factories spreading across a rapidly industrialising Germany – towards the end of 1888. As a child Ebert’s friends had seen him as mischievous; as an apprentice this became rebelliousness, a trait that faded as responsibility revealed a conformist personality and a rigid mind.

Mocked more than once in later life for his original trade – the Weimar Republic’s right-wing press described him as the ‘saddler-President’ – Ebert’s touchy response was to say this was as absurd as calling a general a lieutenant because he had once held that rank. He contained within himself the conflicts of the new Germany with its Catholic south, Protestant north and growing industrial working class. Otto von Bismarck, the Prussian architect of unification, had turned first against the Catholics and then against the socialists, fearing that both had loyalties beyond the state he was constructing – the Catholics to Rome, the socialists to Marxist internationalism. Ebert, who was born a Catholic and became a socialist, straddled the Empire’s ‘outsider’ groups.

Germany’s first significant working-class party – the Socialist Workers’ Party of Germany (SAPD) – was established in 1875. Three years later, following two assassination attempts on Kaiser Wilhelm I, allegedly by socialists, Bismarck, now Imperial Chancellor, banned the SAPD from organising, exiling the party’s most prominent activists and theoreticians. He placed no obstacle in the way of Socialists contesting for seats in the Reichstag, which, though elected, was impotent. Bismarck had also feared a working class and liberal middle class alliance that would press for parliamentary democracy.

The ban – which extended to socialist trade unions – was to last until 1890. It was, therefore, an underground party that Ebert joined in 1889, encouraged by an uncle in Mannheim. His apprenticeship complete, Ebert began seeking work as a journeyman – the first stage towards the status of self-employed master – at the same time joining the saddle makers’ union. He moved between Brunswick, Frankfurt, Hersfeld, Kassel and Hanover, taking what work he could find, meanwhile organising, building a reputation from town to town among the predominantly skilled workers attracted to trade-unionism and then to socialist politics. Ebert’s commitment and competence as an activist stood out and in 1890 he was elected secretary of the union federation in Hanover.

Still in his teens, Ebert had found the role he was to make his own, culminating with his arrival at the summit of the German state. He was prepared to carry out the organisational routines few were keen to undertake, acting as the negotiator and master of detail, the puller of strings. But in conditions of illegality and in the economic recession of the early 1890s, Ebert was frequently unemployed, watched by the police and blacklisted by employers. He read widely, Marx and Engels of course, but also Owen and Lassalle. One historian has written: ‘He became convinced that there was no hope for the future of the working classes in a pure capitalistic system.’1 The party’s theoreticians, exiled and with a sense of persecution, took on a more radical cast, using the word ‘revolution’ freely. But, as Karl Kautsky – the ‘Pope of Marxism’ – was to write: ‘It is not a question of a revolution in the sense in which the police use the word, that is to say of an armed revolt.’2

Bismarck complicated matters by instituting a paternalistic welfare state, attempting to bribe the working class into docility with pensions, accident insurance and unemployment benefits, rudimentary but an advance on anything Germany’s European neighbours had achieved. When, after dismissing Bismarck in 1890, the newly enthroned Kaiser Wilhelm II lifted the ban on socialist parties in an attempt to win the workers’ affection, the party re-emerged as the German Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands – SPD). The self-proclaimed Marxist SPD’s 1891 Erfurt Programme set out ‘maximum’ and ‘minimum’ demands – the maximum looking confidently to capitalism’s inevitable and even imminent collapse (making the party prone to a comfortable fatalism); the minimum seeking a range of reforms including genuine parliamentary democracy, a thoroughgoing welfare state financed through direct taxation, and the eight-hour working day. The SPD fell into the paradox that haunted its history – radical rhetoric masking reformist practice, the contradiction between the two carefully evaded until brought sharply into focus by war and revolution, with Ebert playing a central part.

Ebert’s travels brought him in May 1891 to the North German city of Bremen, a port on the river Weser, where he remained for 15 years. Bremen combined a captivating attractiveness with a staunch sense of local autonomy. In 1871 the city’s population had been a little over 80,000; when Ebert left this had soared to almost a quarter of a million, boosted by industrialisation. In 1878 there had been fewer than 6,000 workers in Bremen’s manufacturing sector; within 20 years their number would rise almost six-fold, with an accompanying increase in SPD membership.

Ebert made efforts to establish himself as an independent craftsman, with little success. Taking whatever casual opening was available, he lived precariously, combining work with trade union and SPD activism. He agitated for the democratisation of Bremen’s local government, while at the same time pressing for centralisation of the trade union and SPD machinery. His position accorded precisely with that of the skilled workers becoming unionised and joining the now legal SPD, seeking to improve their status and conditions in a capitalist state rather than acting as shock troops to topple it.

In 1893 Ebert married Louise Rump, a working-class woman who shared his politics. Ebert’s lifelong friend Hermann Müller (they first became acquainted in the Bremen SPD) believed a settled family life made Ebert more conciliatory in nature, giving his politics a firmer foundation. The couple’s first child, also called Friedrich, was born in September 1894. They were to have in all one daughter, Amalie, and four sons, two of whom were killed in the First World War, both in 1917. I have lost two sons for this Empire, Ebert told the Imperial Chancellor in 1918 when the latter questioned his commitment.3 Friedrich junior was wounded.

Ebert’s politics notwithstanding, he had a working relationship with Bremen’s capitalists. Towards the end of 1893 negotiations with the owners of a local brewery, Beck’s, concluded with Ebert becoming an innkeeper, the brewers setting him up in business in return for a guaranteed outlet for their beer. A socialist landlord could count on socialist and trade union customers. As the SPD renewed its organisation and recruitment, the parteikneipe (party tavern or pub) served as both a social and political centre. Ebert’s wife and mother-in-law helped with the day-to-day running of the business. The ‘hail fellow well met’ aspect of inn keeping was not to Ebert’s taste, his wife reputedly reproaching him on one occasion, ‘As a host you should not look like a vinegar merchant who has had to drink his own vinegar’.4

‘As a host you should not look like a vinegar merchant who has to drink his own vinegar.’

LOUISE EBERT

LOUISE EBERT

Ebert soon transformed the inn into the Bremen SPD headquarters, placing himself at the centre of the city’s party and trade union activity. Now 22 and freed from the uncertainty of an existence as an employee, Ebert matured as an administrator – energetic and unfailingly precise – and as a speaker. Though never an inspiring orator (like Rosa Luxemburg), or a sophisticated Marxist wordspinner (like Karl Kautsky), what Ebert said carried the weight of his organising experience. His election as local party chairman in 1894 marked the beginning of his rise to power nationally. In the same year Ebert became editor of the SPD city paper, the Bremer-Bürgerzeitung, a post paying 25 marks a week and which he held for six years. Ebert’s reputation grew with his appearance as a delegate at the 1896 Gotha national congress and his election as an SPD member on the Bremen city council in 1899. In 1900 he became party leader on the council and the city’s first paid labour secretary, holding trade union activity throughout the city together, advising members on employment rights, intimately involved with their everyday lives.

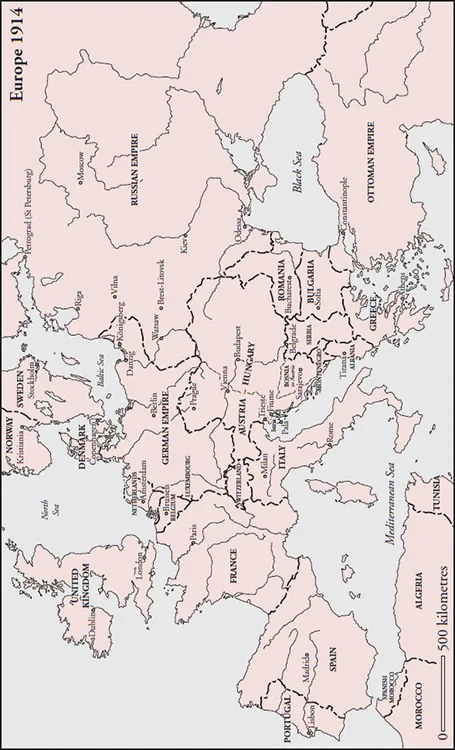

Ebert’s rise in the Bremen party coincided with the country’s transition from an agricultural to an industrial economy, with an expansion that would enable Germany to challenge then outstrip her nearest European rival, Britain. Germany’s population rose from 41 million in 1871 to 68 million in 1913. As a latecomer to industrialisation, Germany was not – unlike Britain – encumbered with outdated techniques and combined an efficient and rigorous educational system with scientific and financial innovation. German iron and steel output rose from 4.1 million tons in 1880 to 6.3 million in 1900 and soared to 17.6 million in 1913. By comparison, British production fell from 8 million tons in 1880 to 5 million in 1900, rising only to 7.7 million in 1913. German steel production in 1913 exceeded that of Britain, Russia and France combined. Germany was second to none in the production of electrical, chemical and pharmaceutical goods. In the first decade of the 20th century Germany’s exports rose by over 90 per cent, Britain’s by only 75 per cent, and by 1913 German sales abroad almost equalled those of Britain. If France shuddered at the military implications of her neighbour’s soaring population and impatient energy, Britain eyed warily Germany’s burgeoning industrial power and naval ambitions.

The new Germany was a contradictory but dynamic combination of absolutism and democracy. In 1875 Marx had pointedly portrayed Bismarck’s creation as a ‘bureaucratically constructed military despotism, dressed up with parliamentary forms, mixed in with an element of feudalism yet at the same time already influenced by the bourgeoisie’.5 Every day the working class was left in no doubt that it lay outside society, discriminated against in the electoral system of the states making up Germany, particularly in the largest, Prussia. Compulsory military service – with militarism the glue holding the nation together – heightened the sense of a tight hierarchical order (the officer corps saw the barracks as the ‘school of the nation’) but confirmed a nagging class-consciousness. The Kaiser’s earlier sympathy for the proletariat having waned, during a Berlin tramworkers’ strike in 1900 he blustered, ‘I expect, if the troops are called out, at least five hundred people to bite the dust.’6

The paradox for Ebert’s party was that while delegates to annual congresses traditionally declared a theoretical enmity to capitalism, confident that the system was inevitably doomed, capitalism – despite periodic crises – was thriving and creating a prosperous industrial working class. Wages were rising and a substantial section of the workforce, particularly the skilled who were the mainstay of SPD membership, saw real improvements in their standard of living. Income per capita doubled in Germany between 1870 and 1913. How could this be reconciled with the party’s conviction that workers’ conditions would worsen, that capitalism would collapse and socialism would emerge? The party’s membership rose from an estimated 100,000 in 1890 to almost 400,000 in 1904 and over a million in 1914. The growth mirrored the steady increase in SPD votes in elections to the Reichstag – from 312,000 in 1881, to 1,427,000 in 1890, and to over three million in 1903.

A party theoretician, Eduard Bernstein, suggested in the late 1890s that Marx had been mistaken, that capitalism was not about to disintegrate, that its crises were manageable, and that the SPD’s objectives required revision. Calling the party programme into question, he wrote, ‘I frankly admit that I have extraordinarily little feeling for, or interest in, what is usually called “the final goal of socialism”. This goal, whatever it may be, is nothing to me; but the movement is everything.’7 Bernstein considered the SPD would achieve more by working with bourgeois liberals to create a genuine parliamentary democracy. Passing one good factory law, he once said, might contribute more to the workers’ welfare than nationalising an entire industry. The party was riven with bitter debates and Bernstein’s revisionism was rejected at party congresses in favour of radical rhetoric. Ebert kept his distance from the revisionists but shared their views in practice, declaring in 1901, A state can work in the interest of the general good only if it gives an opportunity to all classes of the populace to participate in governing, in administering, and in developing the state.8 The party’s task was to find a place for the working class in the Imperial state, not overthrow it.

‘A short fat man, with short legs, a short neck, and a pear-shaped head on a pear-shaped body.’

SEBASTIAN HAFFNER ON FRIEDRICH EBERT

SEBASTIAN HAFFNER ON FRIEDRICH EBERT

August Bebel, the party’s leader since 1875, regarded Ebert as too moderate for his orthodox Marxist taste in 1904 and blocked an advance in his career. Ebert presided over that year’s SPD congress in Bremen. Bebel’s co-chairman, Paul Singer, was impressed with Ebert’s conduct of the congress, recommending his selection as a paid official. Bebel vetoed this. But a year later he relented and the party delegates confirmed Ebert’s appointment as a secretary on the executive. Reformist trade union leaders were prominent in Ebert’s support, confident that he would provide organisational ability and dogged reliability to an SPD transforming itself from an agitational faction to an electoral machine.

The SPD executive was made up of two co-chairmen – Bebel and Singer – a treasurer and four secretaries. One historian of the SPD describes the new recruit to the party leadership: ‘Colorless, cool, determined, industrious, and intensely practical, Ebert had all those characteristics which were to make of him, mutatis mutandis, the Stalin of Social Democracy.’9 This is unfair. Ebert may have shared Stalin’s preference for administration over idealism, but not his personal cruelty. Stalin wrote poetry and robbed a bank in his early life; it is hard to imagine Ebert contemplating either. His hair still black, the 35-year-old Ebert’s appearance contrasted sharply with that of the older generation of SPD leaders. An unsympathetic writer describes him, unflatteringly but accurately, as a ‘short fat man, with short legs, a short neck, and a pear-shaped head on a pear-shaped body’.10

Ebert arrived at the Berlin headquarters early in 1906 to discover ramshackle offices and casual administrative practices more appropriate to the SPD’s origins as a sect than the major political force it aspired to be. Party reforms agreed over the previous two years made it clear that the SPD saw its future in the Reichstag rather than in the streets, with a tiered structure based on electoral constituencies. Ebert’s personality and talents ensured those reforms would be rigorously pursued. He was initially deputed to assist the treasurer, the ageing revisionist Karl Gerish, in collating membership statistics and subscription records. The office had no typewriter, no telephone and no clerical assistance, deficiencies Ebert made good within a year. He formalised an organisational hierarchy, using to the full the party’s new insistence on regular and detailed written reports from regional and constituency officials, gnawing away at local autonomy.

The party’s radical wing had hoped that a tighter, more centralised organisation would thwart the revisionist heresy. In practice, the bureaucracy – which sought stability above all – served the interests of moderates and reformers. Within a few years of Ebert’s arrival on the executive, the rapidly-growing party had over 4,000 paid officials and a further 11,000 salaried employees. The contemporary German social theorist Max Weber would cite Ebert as a prime example of the political bureaucrat, the ambitious functionary of a state within a state. Heinrich Müller, who soon joined his friend Ebert on the executive, once boasted that he had never read Marx’s Das Kapital. Many, though not Ebert, could probably have said the same. Radical thoughts mi...

Table of contents

- Friedrich Ebert: Germany

- Contents

- Prefac: The enemy’s revengeful hysteria

- Part I: The Life and the Land

- 1. The Party Man, 1871–1913

- 2. The War, 1914–18

- 3. Defeat and Revolution, 1918–19

- Part II: The Paris Peace Conference

- 4. Setting the Terms, 1919

- 5. Signing the Peace, 1919

- Part III: The Legacy

- 6. The Brittle Republic, 1919–25

- 7. The Unravelling of Versailles, 1925–45

- Notes

- Chronology

- Further Reading

- Picture Sources

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Friedrich Ebert by Harry Harmer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.