- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

World War I sounded the death knell of empires. The forces of disintegration affected several empires simultaneously. To that extent they were impersonal. But prudent statesmen could delay the death of empires, rulers such as Emperor Franz Josef II of Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Sultan Abdülhamid II. Adventurous rulers - Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany and Enver Pasha in the Ottoman Empire - hastened it. Enver's decision to enter the war on the side of Germany destroyed the Ottoman state. It may have been doomed in any case, but he was the agent of its doom. The last Sultan Mehmet VI Vahdettin thought he could salvage the Ottoman state in something like its old form. But Vahdettin and his ministers could not succeed because the victorious Allies had decided on the final partition of the Ottoman state. The chief proponent of partition was Lloyd George, heir to the Turcophobe tradition of British liberals, who fell under the spell of the Greek irredentist politician Venizelos. With these two in the lead, the Allies sought to impose partition on the Sultan's state. When the Sultan sent his emissaries to the Paris peace conference they could not win a reprieve. The Treaty of Sèvres which the Sultan's government signed put an end to Ottoman independence. The Treaty of Sèvres was not ratified. Turkish nationalists, with military officers in the lead, defied the Allies, who promptly broke ranks, each one trying to win concessions for himself at the expense of the others. Mustafa Kemal emerged as the leader of the military resistance. Diplomacy allowed Mustafa Kemal to isolate his people's enemies: Greek and Armenian irredentists. Having done so, he defeated them by force of arms. In effect, the defeat of the Ottoman empire in the First World War was followed by the Turks' victory in two separate wars: a brief military campaign against the Armenians and a long one against the Greeks. Lausanne - where General Ismet succeeded in securing peace on Turkey's terms - was the founding charter of the modern Turkish nation state. But more than that it showed that empires could no longer rule peoples against their wishes. This need not be disastrous: Mustafa Kemal demonstrated that the interests of developed countries were compatible with those of developing ones. He fought the West in order to become like it. Where his domestic critics wanted to go on defying the West, Mustafa Kemal saw that his country could fare best in cooperation with the West.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access From the Sultan to Atatürk by Andrew Mango in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

Sèvres

1

Illusions of Power

The First World War destroyed the comfortable certainties of the ruling class throughout Europe. Like the aristocrats who had survived the French Revolution, the rulers of Europe were left with only nostalgic memories of the douceur de vivre of the old order. The mass slaughter on the Eastern and the Western Fronts gave the lie to widely-held illusions. Belief in the inexorable progress of civilisation died on European battlefields where the most advanced nations of the world fought each other with the most inhuman weapons and methods they could devise. Barbarians could have done no worse. But other illusions survived. One such was that not all empires were doomed, that while outmoded dynastic empires, like those of the Habsburgs, Romanovs and Ottomans, fell apart, the progressive empires of Britain and France, which had a democratic core, had emerged strengthened by the defeat of their rivals.

When the war ended, Britain, France, Italy and the United States – known as the Principal Allies – thought they could dispose as they wished of the fates and possessions of their enemies. This illusion of omnipotence was disproved first in Russia, then in Turkey and finally and catastrophically in Germany. The emergence of the Bolshevik empire with its centre in Russia, of the Turkish national state and then of the truly evil empire of the Nazis in Germany marked the failure of Allied policies. They had hoped that the First World War would be the war to end all wars, and that it would make the world safe for democracy. These hopes were quickly disappointed. The post-war settlement was short-lived, except in one case. The emergence of a fully independent, stable Turkish national state within the community of civilised nations was a fortunate, if unintended, consequence of the policies of the victors of the War, which we can now see for what it was – a brutal civil war within the Western World.

The Ottoman state entered the fray in 1914 in a reckless gamble by a group of adventurers, led by a triumvirate consisting of two young career officers, Enver and Cemal, and one civilian, Talât. Enver, the leading spirit, was 33 years old in 1914, Cemal was 42 and Talât 40. Enver became Commander-in-Chief (formally Deputy Commander-in-Chief, since the Sultan was nominal C-in-C), Cemal Navy Minister, Commander of the Southern Front and Governor of Syria (which included Lebanon and Palestine), and Talât Minister of the Interior and then Grand Vizier (Prime Minister). These leaders of the Young Turks, as they were known in the West, had risen to power and fame in Ottoman Macedonia in the first decade of the 20th century. Their character had been moulded by their experience in fighting the irregular bands of Balkan nationalists – Slav Macedonians, Bulgarians, Greeks, Serbs and, finally, Albanians. Nationalist irregulars were known in Turkish as komitacı (committee-men), a designation which became a byword for ruthlessness, violence and treachery, but also reckless courage. Such men were needed to carve nationally homogeneous states out of a multinational empire – a process which involved massacres, deportations and the flight of millions of refugees. Enver, Cemal and Talât were Turkish komitacıs in a literal sense too, as leaders of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), whose members were known as Unionists (İttihatçı). They were initiated in quasi-Masonic ceremonies in which oaths were sworn on guns and holy books. They conspired against the absolutist regime of Sultan Abdülhamid II, forced him to reintroduce constitutional rule in 1908, deposed him in 1909 and seized power in a coup in 1913. They believed initially that constitutional rule would reconcile all the ethnic communities of the Ottoman Empire and turn them all into loyal Ottoman citizens under the banner of freedom, fraternity and justice. It was their version of the ideals of the French Revolution, which they admired as the Great Revolution. But they admired Napoleon even more and also the German and Japanese militarists whose example confirmed their belief that might was right.

THE CUP TRIUMVIRS

Enver (1881–1922) became a leading member of the Committee of Union and Progress in Salonica, where he was serving as a staff major with the Ottoman Third Army, and won renown as the best-known of the military mutineers who secured the reintroduction of the constitution in 1908. He played a leading role in the suppression of the counter-revolution in Istanbul the following year and, after raising local resistance to the Italians in Cyrenaica, was the main author of the coup which brought the CUP to power in 1913. He married the Sultan’s niece in 1914, and became War Minister, Chief of the General Staff and (Deputy) Commander-in-Chief after pushing the Ottoman Empire into the First World War on the side of Germany later that year. Enver was seen as the leading pro-German triumvir, so much so that the Germans referred jokingly to Turkey as ‘Enverland’. He fled to Germany in 1918, and after a vain attempt to take over the Turkish resistance movement in Anatolia, moved to Central Asia where he was killed by the Red Army.

Cemal (1872–1922) was the triumvir to whom Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk) was closest. A member of the CUP central committee in Salonica, he restored order in Adana after a bloody anti-Armenian pogrom in 1909, served as Governor of Baghdad, and became Military Governor of Istanbul after the CUP seizure of power in 1913. He was Navy Minister and at the same time Military Governor of Syria and overall Commander of the Southern Front during the First World War. He fled the country in 1918 and was murdered by an Armenian terrorist in Tbilisi (Georgia) in 1922.

Talât (1874–1921) was a lowly post office clerk when he joined the CUP, rising to a leading position within the movement in Salonica. He became Interior Minister in 1913, and was the main author of the deportation of Armenians from Anatolia in 1915. He rose to the top post of Grand Vizier (Prime Minister) in 1917. Along with the other two triumvirs, he escaped in a German warship in 1918, and was assassinated by an Armenian militant in Berlin in 1922.

Enver (1881–1922) became a leading member of the Committee of Union and Progress in Salonica, where he was serving as a staff major with the Ottoman Third Army, and won renown as the best-known of the military mutineers who secured the reintroduction of the constitution in 1908. He played a leading role in the suppression of the counter-revolution in Istanbul the following year and, after raising local resistance to the Italians in Cyrenaica, was the main author of the coup which brought the CUP to power in 1913. He married the Sultan’s niece in 1914, and became War Minister, Chief of the General Staff and (Deputy) Commander-in-Chief after pushing the Ottoman Empire into the First World War on the side of Germany later that year. Enver was seen as the leading pro-German triumvir, so much so that the Germans referred jokingly to Turkey as ‘Enverland’. He fled to Germany in 1918, and after a vain attempt to take over the Turkish resistance movement in Anatolia, moved to Central Asia where he was killed by the Red Army.

Cemal (1872–1922) was the triumvir to whom Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk) was closest. A member of the CUP central committee in Salonica, he restored order in Adana after a bloody anti-Armenian pogrom in 1909, served as Governor of Baghdad, and became Military Governor of Istanbul after the CUP seizure of power in 1913. He was Navy Minister and at the same time Military Governor of Syria and overall Commander of the Southern Front during the First World War. He fled the country in 1918 and was murdered by an Armenian terrorist in Tbilisi (Georgia) in 1922.

Talât (1874–1921) was a lowly post office clerk when he joined the CUP, rising to a leading position within the movement in Salonica. He became Interior Minister in 1913, and was the main author of the deportation of Armenians from Anatolia in 1915. He rose to the top post of Grand Vizier (Prime Minister) in 1917. Along with the other two triumvirs, he escaped in a German warship in 1918, and was assassinated by an Armenian militant in Berlin in 1922.

Constitutional rule did unite the nationalists of the Ottoman state – but it united them against the Turks. Sultan Abdülhamid II had preserved his dominions for 30 years by dividing his internal and external enemies. The advent to power of the Young Turks in 1908 prompted the neighbours of the Ottoman state to attack it both singly and jointly. First, nominal Ottoman suzerainty was repudiated in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bulgaria and Crete; then, in 1911, Italy invaded Tripolitania and Cyrenaica (known today as Libya), the Ottomans’ last directly administered territory in Africa; and finally, in 1912, the small Balkan states – Montenegro, Serbia, Bulgaria and Greece – joined forces to end Ottoman rule in Macedonia. The Young Turks scored their only success in 1913 when the Balkan allies fell out among themselves, allowing Enver to reclaim Edirne (Adrianople) and with it eastern Thrace up to the River Meriç (Maritza/Evros) as the last Ottoman foothold in Europe.

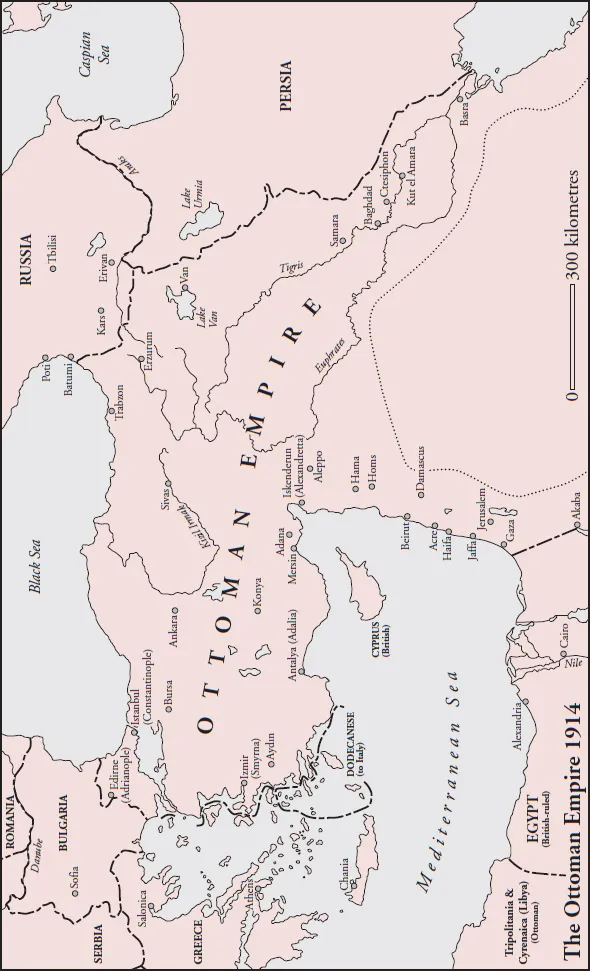

In the West, the Ottoman Empire had long been known as Turkey. In 1914 the Sublime State (its official name in Turkish) had in fact become Turkey-and-Arabia, and even in its remaining territories its hold was uncertain. That year, it had been forced to promise special rule for the six so-called Armenian provinces in eastern Anatolia, where in fact the Armenians were outnumbered by Turks, Kurds and other Muslims. In the Arab provinces there were stirrings, feeble but ominous, of indigenous nationalism, while Turkish troops had to be stationed in the remote (and useless) province of Yemen to keep its feudal ruler under control. The Turkish domestic opponents of the CUP had every right to describe its leaders as bunglers who had promised to safeguard the Ottoman state, but in fact hastened its disintegration. Like unlucky gambling addicts, Enver and his companions pinned their hopes on a new throw of the dice.

Apologists for the Unionist triumvirate have advanced various justifications for their decision to join the Central Powers – Germany and Austria-Hungary. Cemal, they said, had been cold-shouldered when he sought an alliance with France. Britain, they argued, incurred the hostility of the Turks by seizing without compensation two battleships which were being built in British yards with the voluntary subscriptions of Ottoman subjects. But that was in August 1914 when the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, had solid grounds for believing that the CUP leadership had decided to side with Germany. The fact is that the leaders of the CUP wanted to win back some of their losses in the Balkan Wars, and in particular the Greek islands lying off the Turkish coast in the Aegean, that they sought compensation at the expense of Russia in the east for losses they could not retrieve in the west, and that they believed that the Ottoman state had to ally itself with one or the other of the two blocs in order to survive. The CUP leaders had wide-ranging military ambitions, but they lacked the resources to finance them. Germany promised the necessary cash, weapons and technical expertise.

Throughout most of the 19th century the Ottoman state could rely on Britain to keep the Russians out of the Turkish Straits and the imperial capital, Constantinople/Istanbul. But in 1908 in order to counter the threat of German domination of Europe, Britain recruited Russia in support of its entente cordiale with France.1 On the eve of the war in 1914, a plan backed by Russia to appoint a Christian or European governor for an ‘Armenian province’ was blocked by Germany, thanks to whose mediation the governor became, less objectionably, an inspector-general. By entering the war on the side of Germany, the Young Turks got rid of the inspector-general.2 But Turkey could have achieved the same result, if not more, by playing off Germany against the Triple Entente without committing itself to either side. Instead, it concluded an alliance with Germany under the cloak of neutrality and then launched an attack on the Russian fleet in the Black Sea without a preliminary declaration of war, setting a precedent for Pearl Harbor. The Ottoman cabinet was not even informed of this act of aggression which was staged by the Unionist triumvirate.

The Ottoman state thus became the eastern wing of the German-Austro-Hungarian alliance. Its communications with Germany were made safe when Bulgaria joined the Central Powers in order to make good its losses in the Second Balkan War, and when Serbia (whose nationalists had ignited the fuse of the conflict) was overrun at the end of 1915. But while the railway line from Berlin to Istanbul was adequate, communications between the Ottoman capital and its eastern and southern fronts relied on the unfinished single-track Baghdad railway built by the Germans. As the tunnels through the Taurus mountains were not completed until the end of the war, men and supplies had to cross the range on foot and on pack animals. The line ended at the northern edge of the desert between Syria and Mesopotamia, a long way from the Russian front. In the south too there were big gaps in the railway network between Aleppo and the Egyptian frontier, where the Ottomans faced British imperial forces.

There was little industry in the Ottoman state, which could just about manufacture uniforms for its troops, and simple small arms. In the 19th century, the Ottomans had entered the world economy as exporters of handicrafts, such as carpets, and of cash crops, mainly tobacco and dried fruit. Even in peacetime, Istanbul relied on imported Russian grain, sugar and tea. In wartime, as the country’s largely rural economy was disrupted by conscription and military operations, malnutrition was widespread and starvation a constant danger.

According to official statistics, the total population of the state was 18.5 million, of whom 15 million were Muslims – Turks, Arabs, Kurds and others. British sources put the total higher – at 21.5 million for the Asian provinces alone. In the census, people were classified by religion and not by ethnic origin or mother tongue. However, an analysis of provincial statistics suggests that the number of Arabic-speakers was probably around six million, and of Kurds two to three million. Nomadic tribal Kurds and Arab Bedouin eked out a meagre subsistence by breeding sheep, goats and camels, and by extorting protection money from the state, from travellers and from settled populations generally. But even in the relatively advanced provinces, some 90 per cent of the Muslims were illiterate. Tuberculosis, malaria, and trachoma (an eye disease which causes blindness) were endemic. Average life expectancy was 30 years. In wartime malnutrition, typhus and typhoid took a heavy toll.

However, the backwardness of the Asian provinces, which made up the bulk of the state, could be easily forgotten in the cosmopolitan centres – the capital, Constantinople/Istanbul, and the port cities of Smyrna/İzmir on the Aegean and of Trebizond/Trabzon on the Black Sea. In the capital, non-Muslims made up 40 per cent of a population of approximately one million, and dominated trade and the professions. In Smyrna, nicknamed ‘infidel İzmir’ by the Turks, there were more Christians than Muslims.3 Istanbul and İzmir were European cities, with good schools, theatres, electric trams and gas lighting. Istanbul was a world in itself, where magnificent monuments from the city’s past – mosques, palaces, but also rich mansions – fostered illusions of grandeur. These illusions were not confined to Turks and other Muslims.

The Greeks who made up the second largest community in Istanbul, and were present in large numbers along the coasts of the Aegean and the Black Sea, had seen their numbers, prosperity and economic power rise throughout the 19th century. The more ambitious among them dreamt of replacing the Turks as rulers of a revived Byzantine Empire. Armenian nationalists disregarded the numerical weakness of their community, which numbered one and a half to two million,4 and set their hopes on restoring the mediaeval Armenian kingdom in eastern and southern Turkey. Of course not all the Greeks and Armenians were nationalists, but the Ottoman state could not rely on the loyalty even of those in the Christian communities who had prospered under its rule.

Nevertheless the Ottoman state punched well above its weight. This was partly due to the hardihood and courage of Turkish conscripts. ‘The Turkish peasant will hide under his mother’s skirts to avoid conscription, but once in uniform he will fight like a lion,’ a Russian expert on Turkey wrote during the war.5 But there was another reason to which most Western observers were blind and which historians have come to notice only recently. While the rural masses were illiterate and ignorant of the modern world, there was an elite of experienced and well-trained Turkish civil servants and army officers. Although the reforms of the 19th century (known as the Tanzimat, meaning ‘the (re)ordering’) were routinely decried in the West as inadequate and a sham, by the beginning of the 20th century Ottoman administration compared well with that of other contemporary empires – so much so that many of its former subjects came to regret its eventual dissolution. A recent study suggests that in the Arab lands placed under British and French Mandates at the end of the First World War, there was little improvement for indigenous Muslims in such basic areas as average life expectancy, education, communications and public order.6 Ottoman civil administration was organised on French lines, while in the army French and British advisers were largely replaced by Germans from the reign of Abdülhamid II onwards. The efficiency of Ottoman governors and commanders was often overlooked by Western critics who decried their rule as backward and corrupt. Foreign observers also overlooked the fact that many of the Greeks, particularly along the Aegean coast, were immigrants from the newly-independent Greek kingdom who found life under Ottoman rule more rewarding than in their own country.

Mehmed V Reşad (1844–1918) acceded to the Ottoman throne in 1909, when his elder brother Abdülhamid II was deposed by the Young Turks. A pious and mild man, who sympathised with the Sufi Whirling Dervishes, he was the country’s first constitutional Sultan. Throughout most of his reign this meant that he did the Young Turks’ bidding. His only reported criticism of the Young Turk war leader Enver Pasha was a remark after a meal. ‘The Pasha drinks water when he eats leeks. It is unheard of.’

Enver and his associates were poor diplomats and bad judges of the national interest. But after the disaster of the Balkan Wars they reorganised the army and turned it into an efficient fighting force, if only to waste it in ill-planned operations. A symbolic explosion marked the declaration of war: a monument erected by the Russians in the Istanbul suburb of San Stefano (today’s Yeşilköy, the site of the modern Atatürk airport) where the Tsarist empire had imposed a peace treaty on the defeated Ottomans in 1878, was blown up and its destruction filmed for Turkey’s first newsreel. As Caliph of the Muslims worldwide, the Sultan – the elderly Mehmed V who did as he was told by the CUP – proclaimed the jihad – a holy war against the Allies. There were doubts that fighting as junior partner of two Christian empires against three other Christian empires could count as a jihad. In any case, Muslims took little notice of the proclamation – Indian Muslims continued to fight in the ranks of the British army, Algerian and Senegalese Muslims in the French army, while the Tsar’s ‘wild cavalry’ depended as ever on Muslim horsemen. As for Arab Bedouins, they kept to their tradition of serving the most generous paymaster – and the British easily outbid the Ottomans.

In the winter of 1914/15, Enver led an Ottoman army to destruction in the snows of the mountains of eastern Anatolia on the Caucasian front, which stretched far from the nearest Ottoman railhead, but lay conveniently close to the Russian broad-gauge rail network. In the south, Cemal pushed to the Suez Canal, which some of his units managed to cross, but the Egyptians failed to rise against their British overlords who drove the Turks back into Palestine. Unsuccessful in their attacks, the Turkish army then scored two notable victories in defensive battles. It beat back the British-Anzac and French attempt to break through the Gallipoli peninsula to Istanbul in 1915, and checked a British advance from Basra to Baghdad the following year, surrounding a British force and forcing it to surrender at Kut al-Amara. It was the high point of the Ottoman war effort, which had an effect on Allied perceptions. The British army came to respect ‘Johnny Turk’ as a good fighter, but Allied governments and diplomats vowed revenge: the Turks’ successful defence of Gallipoli and their dogged resistance in Mesopotamia (today’s Iraq) and Palestine had prolonged the war and vastly increased its cost in casualties and resources. Allied statesmen, whose miscalculations had been exposed, became determined to eliminate once and for all the danger which, they believed, the Turks posed to their empires. This difference in perceptions between soldiers and civilians was to play an important part in post-war developments, which showed that the soldiers had the more realistic view of Turkey’s strength.

The bloody battles in Gallipoli, in which each side lost a quarter of a million men killed and wounded, laid the foundations of the career of a young Turkish officer with political ambitions. Staff Colonel Mustafa Kemal was 34 years old at the time and had with some difficulty secured the command of a Turkish division held i...

Table of contents

- From the Sultan to Atatürk: Turkey

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Note on Spelling and Pronunciation

- Part I: Sèvres

- 1. Illusions of Power

- 2. Broken Promises

- 3. Turks Fight for their Rights

- Part II: Lausanne

- 4. Western Revolution in the East

- 5. At One with Civilisation

- Part III: The Aftermath

- 6. Creating a New State and Nation

- Notes

- Chronology

- Further Reading

- Picture Sources