eBook - ePub

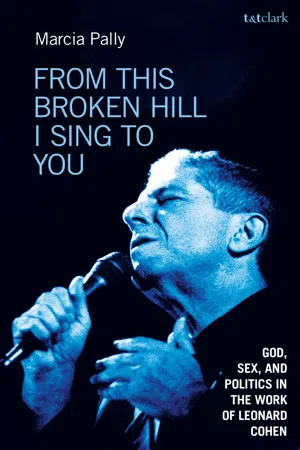

From This Broken Hill I Sing to You

God, Sex, and Politics in the Work of Leonard Cohen

- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Leonard Cohen's troubled relationship with God is here mapped onto his troubled relationships with sex and politics. Analysing Covenantal theology and its place in Cohen's work, this book is the first to trace a consistent theology across sixty years of Cohen's writing, drawing on his Jewish heritage and its expression in his lyrics and poems. Cohen's commitment to covenant, and his anger at this God who made us so prone to failing it, undergird the faith, frustration, and sardonic taunting of Cohen's work. Both his faith and ire are traced through:

· Cohen's unorthodox use of Jewish and Christian imagery

· His writings about women, politics, and the Holocaust

· His final theology, You Want It Darker, released three weeks before his death.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access From This Broken Hill I Sing to You by Marcia Pally in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Jewish Theology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Theodicy: Arguments with God about Evil, Suffering, and God Himself

First Remarks

As this book traces Cohen’s theodicy through his poetic work, we might begin by looking into the sorts of questions that theodicy poses and attempts to answer. While not a detailed introduction to theodicy—several books offer such a course, including Peckham (2018) and Scott (2015)—this chapter aims modestly at providing some general background to the theodical aspects of Cohen’s work. It seeks to highlight a few theodical questions and approaches to addressing them. The chapter is organized by theodical approach rather than chronologically as many key theodicies have been explored over time, and the central ideas within each approach gain clarity when discussed together. Cohen took up some of the theodical questions outlined here throughout his life, others, less so. In this general background chapter, I’ll briefly note the ones of significant import to Cohen. Exploring them as expressed in his work is the task of the rest of the book.

The most important question for theodicy is why suffering and devastation occur when an omnipotent and good God could prevent them. In considering both evil (harmful events, intended or not) and intentional evil or sin, we may ask: why do the wicked succeed in their treachery or at least get away with it (Jer. 12:1; Pss. 10:4-5, 94:3-7)? Why does God allow these things (Jer. 5:19; Pss. 10:1, 11)? “It seems that there is no God,” Thomas Aquinas wrote as he contemplated the atheist retort to evil’s prevalence, “by the word ‘God’ we understand a certain infinite good. So, if God existed, nobody would ever encounter evil. But we do encounter evil in the world. So, God does not exist” (Summa Theologiae: Ia, q.2, a.3, ob 1, cited in Davies and Leftow 2006: 24). In the eighteenth century, the philosopher David Hume put the problem this way: “Is he [God] willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is impotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Whence then is evil (unde malum)?” ([1779] 1990: 108–9).

Over the last century, investigations of why God allows evil often begin by arguing that evil could logically emerge even given a loving, omnipotent God. That is, there is some reason why evil might logically occur. Thus, in light of this reason, the presence of evil does not mean that there is no loving, omnipotent God as both could exist at once (van Inwagen 2006: 7, 65). A second part of the theodical effort is to demonstrate not only that God could exist along with the world’s evil but that, as God is both good and the ground for all existing things, evil (one existing thing) must be part of some greater good. Peter Van Inwagen, in line with much Christian and Jewish theodicy, notes, “A theodicy is not simply an attempt to meet the charge that God’s ways are unjust: it is an attempt to exhibit the justice of his ways” (2006: 6). Importantly, theodicy today as in the past remains an open debate where solutions to the puzzle of evil are proposed but never final or completely satisfying.

This is certainly how Cohen saw it. The aim of theodical questions, on his view, is not to come to an ultimate understanding of God and evil but to better understand our distress-filled world and how to live somewhat better in it. As we’ll see throughout the following chapters, Cohen’s questions, frustrations, and anger at God aim not at a final judgment about him. Rather, they emerge from the recognition that there is much humanity cannot grasp about God but that part of the human task is to try to understand what we can so that we may live better with him and with those he loves, other persons (see Chapters 2 and 3).

A Loving God and Natural Disaster

Theodicies address suffering caused by unintended human error, intended human harm/sin, and natural forces. Starting with natural occurrences—metaphorically unruly forces, watery unformedness (Gen. 1:1), “sea monsters,” and the “leviathan” (Ps. 74:14)—a key theodical question is: why did God, who could have created the world in any way, create natural processes that injure and kill innocents? Why does he not shut the doors to them (Job 38:8)? Voltaire famously confronted these questions in his poem “On the Lisbon Earthquake,” written in response to the palliative explanations given for the 1755 earthquake that, as Voltaire wrote, killed infants at their mother’s breast.

Voltaire challenged Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’s claim that, as a perfect God created the cosmos, it must be “the best of all possible worlds.” Voltaire’s vivid descriptions of nature’s brutality make a case that it is not. He further attacked the idea, popular at the time, that as this is the best possible worlds, all aspects of nature are just as they should be. Thus, no part of nature—including the tectonic geophysics that caused Lisbon’s earthquake—could be changed without disturbing the “chain” of natural laws that God created for this “best” world. In retort Voltaire asked, can’t God make the chain of natural laws operate with less brutality? He further rebutted Alexander Pope’s dictum that “what is, is right”; what exists, is correct. It is unlikely, Voltaire replied, that every Lisbon baby had committed a wrong so grievous as to warrant being crushed under Lisbon’s rubble—thus making the earthquake “right.” He sardonically noted that “what is, is right” includes murder, rape, and so on, which cannot be “right.”

Voltaire’s questions led him to agnosticism. Cohen—perhaps because of the importance of covenant and relationship in Jewish thought (Chapter 2)—doubted neither God’s existence nor his bond with humanity. Indeed, Cohen’s theodical frustration emerged from within his bond with God. But Cohen did raise a query related to Voltaire’s: if all the world’s phenomena are created by God, is God not ultimately responsible? If some things are not “right,” is not God, who made all things, foundationally accountable? More specifically for Cohen, if it’s “right” in God’s vision for each person to act covenantally with God and other persons, when we do not do this “right” thing, is not God ultimately to blame?

A Loving God, Human Evil, and Free Will

Moving from natural disaster to intended human evil/sin, many theodicies find explanation in our free will. As this is among the most important theodical traditions, I’ll discuss it here first. Free will is generally understood as (i) living in circumstances that allow one to take or not take an action or (ii) the absence of external factors forcing one’s hand (e.g., wanting to buy grapes, one cannot go to a shoemaker, but as no external factor is forcing one’s trip to the greengrocer, that choice is freely taken). The first premise of free will theodicies is that free will indeed allows persons to make immoral decisions that cause suffering. But lacking this option, we would be not moral actors but rather machines preprogrammed to always do good. The consequence of being a creature capable of moral choice is the possibility of immoral choice.

The notion that humanity’s free will is the source of worldly evil and suffering is among the first ideas of the Bible, in which the special tree in Eden (Gen. 3) brings not immortality, as in the Gilgamesh epic of neighboring Mesopotamian culture, but rather wisdom. And the wisdom it brings is that humanity has the capacity, the free will, to follow or flout God’s ordering of the natural world (Sarna 1966: 26; Hayes 2012: 40). Adam and Eve may refrain from eating from the tree, following God’s wish, or they may eat from it, flouting God. The decision is theirs and it is of a moral nature: with the freedom to make choices comes responsibility.

On this understanding, evil emerges not from the actions of capricious gods whom one might influence by magic, as in the pantheons of societies surrounding ancient Israel, but “is a product of human behavior, not a principle inherent in the cosmos. Man’s disobedience is the cause of the human predicament” (Sarna 1966: 27). With this knowledge, humanity (Adam and Eve) must leave Eden, their paradisical home of childlike living without responsibility, and enter the adult world of work, childbearing, family, and moral consequences. As the Bible continues, with its stories of righteousness on one hand and idolatry and abuse of the needy on the other, “Humans and humans alone are responsible for the reign of wickedness and death or the reign of righteousness and life in their society” (Hayes 2012: 158).

Understanding evil as emerging from humanity’s free will was also Augustine’s approach in Free Choice of the Will, which set much of the ground for future Christian free will theodicies. An agent lacking the choice to do wrong cannot be a moral agent who decides to do right. “Their unusual power of self-determination,” Kathryn Tanner writes, “means humans can become anything along the continuum of ontological ranks, from the top to the bottom” (2010: 134). The free will to determine one’s actions allows persons to do good, ill, and the range in between.

If God does not control humanity’s free will, does this free will limit God as we do what God wishes us not to do? Free will theodicies hold that it does not. Rather, in the cosmos God created, God can do all that is possible but not what is impossible within his created world (Lewis 2001b: 18). God, in his created world, cannot make a triangle have four sides. In an example that connects us to Cohen’s work on covenant, Michael Horton writes, God “is bound to us (better, has bound himself to us) by a free decision to enter into covenant with us and the whole creation. God is not free to act contrary to such covenantal guarantees” (2005: 33). Covenant is a moral commitment of each party to the other. Thus, humanity must have the free will to accept or reject it. Otherwise, it would not be covenant but pre-set obedience. God, seeking covenant with humanity (and not blind obedience), cannot strip humanity of the free will needed to make this choice. One might say that God gave humanity free will so that we can, among other things, make the moral decision to commit to covenant.

John Peckham (2018) calls the arena of human free will “the rules of engagement” between God and humanity. God, he writes, “ ‘does whatever he pleases’ (Ps. 115:3; cf. 135:6), but he is not always pleased by what occurs because part of what pleases him is to respect, for the sake of love, the free decisions of creatures, which often displease him” (2018: 50). Peckham notes biblical and modern arguments for a “cosmic battle” between God and evil forces that seek to distance humanity from God. He notes also that God neither preempts evil forces from trying to entrap humanity nor does God stop humanity from succumbing to them. For such interference would remove human choice and the potential for moral action (Peckham 2018: 103–4, 107, 113).

Among the most important contemporary advocates of the free will argument is Alvin Plantinga, who distinguishes between a free will theodicy, which explains the necessity of evil, and his free will defense, which more modestly suggests that the presence of evil does not obviate the existence of God or his love for humanity. While God could end evil, the option to do wrong is unavoidable if persons are to act freely as moral beings. As this is a logically sufficient reason for God to allow the possibility of evil, the presence of evil is not proof that God is malevolent or does not exist. As the potential to do wrong is a necessary condition of moral agency, this human capacity is also morally sufficient. It compromises neither God’s goodness (he seeks our moral adulthood) nor his omnipotence (1974a, 1974b). Summarizing his argument, Plantinga writes,

A world containing creatures who are significantly free (and freely perform more good than evil actions) is more valuable, all else being equal, than a world containing no free creatures at all … The fact that free creatures sometimes go wrong, however, counts neither against God’s omnipotence nor against His goodness; for He could have forestalled the occurrence of moral evil only by removing the possibility of moral good. (1974a: 29, 30)

Why is the capacity for moral choice important? To some, not being a machine is desirable in itself, but for theists like Cohen, being a moral agent has two other important features. It is one way we are in God’s image (b’tselem Elohim). As God acts freely, humanity, in his image, has some analogous (limited, imperfect) ability to act freely and make choices. Moreover, the reciprocity of covenant—God commits to humanity, and humanity to God—presupposes that persons are free to make that commitment. They are free to exercise yetzer ha’tov (the will to good) but also yetzer ha’ra (will to evil) and reject covenant. Without this freedom, there is no covenantal agreement, only social engineering. In Lenn Goodman’...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-title Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Song Collections Discussed in This Book

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1 Theodicy: Arguments with God about Evil, Suffering, and God Himself

- 2 Covenantal Theology and Its Place in Cohen’s Work

- 3 From Covenantal Theology to Theodicy: Failing Covenant with God and Persons

- 4 Failing Covenant with God and Persons: Doubled Imagery in Cohen’s Work

- 5 Those Who Did Not Fail Covenant: Moses and Jesus—Cohen’s Jewish & Christian Imagery

- 6 The Double Bind That Is Not a Bond: Cohen and Women

- 7 Betrayal of God, Betrayal of Persons, Political Betrayals: Cohen’s Trinity

- Conclusion: You Want It Darker and Thanks for the Dance—Cohen’s Last Creed

- References

- Index

- Copyright Page