![]()

1

The Paradox of Nonexistent Fat Fashion

An Introduction to the Topic and the Book

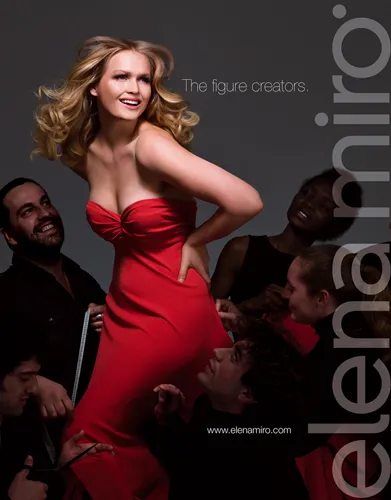

“Fat fashion” is not just a metaphor, it is an oxymoron. An oxymoron is a figure of speech in which two words that have (or seem to have) contradictory meanings are used together. Fat and fashion have apparently contradictory meanings: if something (such as a body, a garment) is fat, it is not fashionable. And what the fashion system considers fashionable is not fat. Of course, there have been several episodes that have combined fatness with fashion recently. New York has been hosting the Full Figured Fashion Week for twelve years. The Italian company Miroglio markets the plus-size brand Elena Mirò, which showed at Milan Fashion Week from 2005 to 2012 and featured in mainstream magazines like Elle UK (see Figure 1). Several top modeling agencies have a plus division, and a few model agencies, such as Bridge in London and Curve Model Management in Hamburg, have specialized in plus-size models. Overweight influencers such as Leah Vernon, to whom Vogue Italia dedicated an entire page of the “Beauty” section in its June 2019 issue, have gained great popularity on social media. Several similar episodes could be mentioned. However, even though many of them exist (and, truth be told, there are not so many), they do not challenge but rather confirm that a fundamental characteristic of fashion is that it concerns lean bodies. As long as plus-size clothing is sealed off into containers that are separate from regular fashion, such as the Full Figured Fashion Week, its marginal position within the fashion system is consolidated rather than called into question.

Figure 1 Elena Mirò advertisement, Elle UK 2008. Courtesy of Miroglio Fashion.

Yet, there is nothing in fatness that is inherently unfashionable, just as nothing in fashion is thin by nature. One might naively think that fat bodies are not fashionable because they are “ugly,” but this would require us to overlook the fact that beauty and ugliness are themselves a product of fashion and other cultural constraints. Fat bodies are not unfashionable because they are ugly; rather, they are perceived as ugly because fashionable bodies are thin.

To be sure, fat fashion is nonexistent. The question that needs asking is why it does not exist, since there is nothing that inherently prevents it from existing. As this book will show in detail, fat bodies are marginalized by the fashion system and plus-size clothing is mostly unfashionable. This has been an enduring condition for many decades now, and a key issue to investigate is what has made it so stable and resistant to change. In recent years, there have been some signs that things are changing. For example, a growing number of plus-size models parade during the main world fashion weeks or appear in the advertisements of major brands published in mainstream magazines. However, they remain isolated or marginal cases within a fashion system that continues to be strongly geared toward the ideal of thinness. In Chapter 7, I shall explain why I feel pessimistic about the real meaning of these signs.

To begin with, we must adequately formulate the question this book seeks to answer. To do so, we need to frame some basic concepts regarding fashion, the body, beauty, fatness, and thinness, and read the topic of fat fashion in the context of the discussion that scholars have long devoted to the tyranny of slenderness. Accordingly, this chapter is intended as a sort of introduction to the topic. I will outline the research question, provide some introductory information, and circumscribe the scope of my argument. In the following chapters, I will return to most of what is anticipated here and discuss it in more detail.

Fashion and the Body

All too often, scholarly works addressing fashion focus on clothing: garments and accessories. This, however, is the effect of an error of perspective caused by the fact that without garments and accessories fashion would not exist. However, fashion is much more than mere garments and accessories. It is, first and foremost, a practice that employs garments and accessories. A practice that bestows certain meanings on clothing, places it in a specific context, thereby making it “act” and produce effects (Breward 2004: 11). In short: it makes clothing live. In other words, in fashion, the use of objects is always framed by behavior, a situation, social relations, and, especially, a body to which those objects relate. Fashion is all of this, and clothing becomes an empty, lifeless shell if it is detached from a body that wears it and from a situation in which it is worn.

At the same time, it is almost impossible not to discuss clothing when dealing with fashion. Indeed, clothing is the topic of this book. Yet, I will attempt to avoid the “materialist” thinking trap described above and instead concentrate on lived fashion, that is, fashion as a form of social action that uses clothing to manage interactions. Fashion is an instance of social action in that it is a kind of behavior that adapts to other people’s expected behavior.1 More specifically, it is a kind of behavior which, in order to adapt to the expected behavior of other people, uses the technical tool of clothing (garments, accessories, even body modifications). People choose to wear certain styles or items of clothing (e.g., a suit and tie) because they expect a certain kind of reaction from others (e.g., respect).

Furthermore, fashion is a social action that is often (but not necessarily) modeled on a particular form of social action, which we also equivocally call “fashion,” although it does not apply exclusively to clothing. It consists of acting according to a temporary social norm. I dress like this because I know that others expect me to dress this way, even though I already know that others’ expectations will soon change, and my clothing style will also change accordingly.

Fashion, therefore, is not just about clothes. The point I am making here goes a little further than the idea—which first emerged in the context of costume history toward the end of the last century—that clothing artifacts must always be analyzed in relation to the sociohistorical context in which they appeared.2 Such a perspective, in fact, essentially regards clothing as an expression or evidence of the social and cultural context in which it was created, produced, and used. The garment is still seen as an artifact, an inert thing, and not the extension of a living body, an inseparable part of the clothes-body complex. Despite its importance for fashion history, the concept is still bound to a materialistic conception of clothing, as it continues to consider clothing something separate and added to the body according to its needs, and not a constituent part of the human body as a “socially exposed” body. By contrast, a considerable portion of the subsequent literature, starting in particular with the seminal work of Joanne Entwistle ([2000] 2015), has recognized that the human body is essentially dressed and that its presence in the social context cannot be understood without referring to clothing (see, e.g., Haller 2015 and Hansen 2004). I concur. As socially exposed human bodies are normally dressed, the function of clothing cannot be understood in isolation from the behavior of the body that wears it. Fashion is a matter of the human body that acts.

At the same time, fashion is of course a feature of industrial capitalism: mass production, the communication society, and consumerism. Although the meaning of the term “fashion” has already been discussed countless times, I feel that a clarification is needed here to explain what kind of fashion is addressed in this book, and particularly why I am focusing especially on the Western fashion system. In the field of fashion studies, a thirty-year-old debate has developed around the relationship between fashion and Western modernity. I think this debate is based on a fundamental misunderstanding.

The debate initially took shape when Jennifer Craik, taking issue with certain “classic” texts on the sociology of fashion,3 spoke of the need to reject “the assumption that fashion is unique to the culture of capitalism” (Craik 1993: 3). Craik challenged the simplistic idea that contrasts fashion, which is changeable and meaningful, with traditional costume, commonly considered static and merely functional. Indeed, transformation and innovation are not absent from non-Western local clothing. Yet Craik did not dispute the specific nature of Western fashion, that is, of what has been called the “fashion system” (Kawamura 2005; Leopold 1992). She did not deny that the fashion system has introduced a new, disruptive element, namely the logic of capitalism and consumer culture, into the processes of creating and circulating clothing. However, many protagonists of the ensuing debate took her thesis to mean that the specific nature of Western fashion should no longer be acknowledged, leading to a tendency for fashion phenomena to be considered in exactly the same way wherever they arise. While this movement has been useful in terms of the history of ideas, since it has helped to legitimize interest in non-Western fashion, it has also hindered our understanding of the peculiarity of the Western fashion system. This complex, global system of clothing innovation, which takes in manufacturing companies, designers, fashion weeks, store chains, mass marketing, and specialized media, is a strictly Western phenomenon, originating in Europe in the modern era and based on the industrialization of clothing manufacture. This is not to deny that multiple modernities exist (Eisenstadt 2000). However, we must acknowledge that today’s global fashion system has its roots in modern European society, subsequently extending its influence over large portions o f the globe on the back of industrial capitalism, as well as Western colonial and post-colonial political power, and well-understood dynamics of cultural imperialism. In its expansion, it continues to be an expression of Western culture, which retains its hold over the creation and control of “pseudo-globalized” fashion, meaning fashion that merely appears to be a global phenomenon.

This book does not deal with fashion in general (à la Craik), but rather with the fashion system, that is the apparatus for creating, manufacturing, retailing, and communicating clothing possibilities, whose headquarters are in the traditional fashion capitals (Paris, London, Milan, and New York), whose concepts are deeply rooted in Western culture, and whose tentacles extend around the globe (Emberly 1987). I have, therefore, decided to restrict my discussion to Western fashion. This choice, besides having the additional advantage of not taking me on a journey into uncharted territory, is based on substantive reasons that I will discuss at the end of this chapter. The nonexistence of fat fashion, the marginalization of fat bodies, the tyranny of slenderness, and all of the key issues that I will discuss throughout, have their origin in the fashion system and are nourished by Western culture. It is the fashion industry that exported them to the rest of the world. As we shall see, the thin ideal that rules the fashion system today did not arise in Africa, South America, or Asia, but in Europe and North America at the beginning of the twentieth century. From there, it went on to contaminate former socialist Central and Eastern European countries (Rathner 2001), Arab countries (Khaled et al. 2018), and almost every other local culture exposed to the fashion system.

Clearly, the limitation of this approach is that I will not be able to talk about the reception and effects of the marginalization of fat fashion in non-Western countries. Although I am analyzing fat fashion as an overarching feature of the (pseudo-)globalized fashion system, that is, a characteristic relevant for Western and non-Western clothing cultures, I am not qualified to consider the unpredictable effects produced by the thin ideal—and the marginalization of fat bodies—when it meets non-Western cultures that did not engender it. This is a vast topic, both from the sociological and costume history perspectives. Yet, it is one that I shall leave for others to discuss.

Size and Look

To return to my starting point—namely, fashion as a practice that employs garments and accessories to manage interaction—if we see fashion as a social practice, the body is immediately implicated. The body, in fact, is a fundamental tool of social interaction. Indeed, it is the only tool that is always necessary for human communication.4 If we acknowledge that fashion is a social practice, we need to recognize clothing as essentially tied to a particular body and situation. A Chanel evening dress is an abstraction; it does not exist by itself in a vacuum. What actually exists is the Chanel evening dress worn by the model in the advertisement in Vogue, or by the actress on the red carpet. Or, perhaps, it exists as the Chanel evening dress that my wife tries on in the department store dressing room. The model with her body, her face, her hair, and the studio setting. The actress with her body, her face, her hair, and the context of her professional performance. My wife with her body, her face, her hair, and the life context in which she imagines wearing that dress.

To clarify this idea, I shall use the concept of “the look.” The individual look, in fact, goes far beyond the mere sum of the garments that a consumer buys, owns, and uses. It refers to our overall appearance as a tool for social interaction. In addition to clothing, it includes make-up, hair care, body shape manipulation (diets, gymnastics, cosmetic surgery), body adornment (tattoos, piercing), and body discipline (posture, movements, mimicry). Furthermore, our look is something that each of us curates every day, rearranging our body in relation to the life situations and practices in which we are involved. Our look is the appearance we care about. As the term itself implies, it is the appearance that everybody “stages” in view of the “look” of others (Goffman 1959). It feeds on the presence of the other and the anticipation of the judgment of the other. A judgment that is not only aesthetic, but existential and relational: who is this person I am meeting? What do you want from me? What can I expect from you? Should I trust you or not? Do I let myself get emotionally involved or hold back? Compared to the concept of body image, which is widespread in psychology and in the literature on eating disorders,5 the concept of the look allows us not to neglect the variability of clothing as it depends on the variability of life contexts. The look is, one might say, relational: it originates from the encounter with the other and takes shape through the anticipation that we produce of that encounter. Entwistle and Slater (2012: 17) describe the look of models as “an object of calculation, something continuously worked upon, molded, contested, performed, something that is [. . .] constantly de- and re-stabilized in new forms.” The same is true for ordinary people, that is ourselves, as through the look we can navigate a situation, the day, and, ultimately, life in a direction that we may or may not like. This is what makes caring about appearance so important. Chapter 2 will address in more detail this clothes-body complex and the role it plays in social life.

The look is therefore a multilayered concept arising from the encounter between the body, clothing, situation, and others. Each of these terms refers, in turn, to a multiplicity of elements. Some of them (such as hair, shape, or shoe color) can easily be modified by the subject, while others (such as skin color, the range of products availab...