![]()

1

Introduction

Engaged Buddhism

Engaged Buddhism is a term used to describe a form of Buddhism that focuses on politics, society and the environment. In engaged Buddhism there is an emphasis upon both personal and social transformation. It is involved with a wide range of social and political issues that have arguably not formed the basis of Buddhist thinking in the past. It forms part of the Buddhist encounter with race, ethnicity and identity. It is also a Buddhist conversation with ideas about human rights, sexuality, gender and politics. It proposes that the causes of suffering are not only found within the mind but can also be found in society, in political oppression and in social inequality. A political ideology, an ecological strategy or an ethnic identity might enforce greed, hatred and delusion. Therefore, engaged Buddhist traditions strive to tackle these issues and alleviate suffering. One of the defining features of engaged Buddhism is that it addresses a wide range of social, political, economic and environmental issues.1 The reason for this is where it locates suffering.

The idea of suffering is central to Buddhism. In one understanding of suffering, the causes are internal – that is, they are in the mind. Suffering is caused by craving things that can never bring satisfaction, because they are impermanent. In the second understanding, the causes of suffering can be found in the world – in a corrupt and uncaring government, in an oppressive political ideology, in a society that does not allow for individual sexual identity, in one that destroys the natural environment, or one that does not protect one’s religious and cultural identity (Bodhi, 2009: 2). This book is concerned with describing the latter, but its ideas originate in the former.

Many studies of engaged Buddhism use the term as a moral category. Engaged Buddhism is based upon the ethically sound principles of Buddhism. The term is applied to those Buddhist groups with a moral or ethical message. In describing engaged Buddhism this is often the case. Engaged Buddhists campaign against social inequality, racial discrimination, the climate crises and gender discrimination. They create strategies based upon Buddhist principles to fight addiction; they visit prisons to act as Buddhist chaplains; and they form grass roots organizations around Asia to help those orphaned and in need. They use Buddhist teachings in a constructive way, and engaged Buddhism means those Buddhist groups that we approve of. These are all essential aspects of engaged Buddhism.

However, I would like to briefly explain why I think we need to widen our understanding of precisely what constitutes engaged Buddhism. Buddhism usually follows a universal message which goes beyond local, cultural and sectarian ideas related to politics and identity. As I will describe, there are also local and ethnic expressions of Buddhism, and these can give rise to distinct expressions of engaged Buddhism. There can sometimes be a tendency in descriptions of Buddhism to reject Buddhist culture when it tends towards sectarianism, becomes violent and is chauvinistic. Although I argue that engaged Buddhism is primarily passive, I will not ignore more local and aggressive expressions of it.2 I intend to use the category of engaged Buddhism to analyse Buddhist groups, movements and individuals who apply Buddhist ideas to tackle inequalities, problems, injustices, political and social structures in ways that might not meet with general approval. These are still Buddhists who are engaged Buddhists: they are using Buddhist ideas, doctrines, identities and methods to overcome suffering in the modern world.3 I am therefore widening the vocabulary of engaged Buddhism to include Buddhist groups with a passive message and those based upon local ethnic identities.

In this book I will argue, as I have indicated, that engaged Buddhism is not necessarily liberal, progressive and non-violent. One of my key points is that in studying engaged Buddhism we are analysing the activities of Buddhist communities who are reacting to suffering in ways that they might not have done in the past. There are two reasons for this. Either the causes of suffering in the twenty-first century were not apparent in the ancient history of Buddhism, or, put quite simply, engaged Buddhists are interpreting Buddhist teachings in new and innovative ways. I accept scholarly critiques of engaged Buddhism – for example, Temprano (2013) and Lele (2019) offer valid and often brilliant critiques of engaged Buddhism. However, I also think that some Buddhists, at various points in history and in different geographical locations, have practised Buddhism in ways that I describe in this book.

This book is not intended to be a history of engaged Buddhism, exhaustive in discussing Buddhism from different cultures, schools or groups, or to offer case studies of engaged Buddhism (though I do occasionally discuss the latter). Rather, I am more concerned with furthering our understanding of engaged Buddhism by considering the theories and philosophies which form its basis. It is, then a theology of engaged Buddhism. More precisely one could term the approach a critical, constructive Buddhist theology. By this I mean that I am myself engaging with the material; my selections made of what I discuss are made, in part, because I think that they are important themes, ideas, conceptual categories, doctrines, and Buddhists who taught them. Different writers could and indeed would have chosen differently. I also want to make sense of engaged Buddhist movement s and to offer a conceptual map of the field so that students can become familiar with the conceptual terrain and be enabled to also constructively engage with engaged Buddhism. I offer in this book some of the skills to become literate in the understanding of engaged Buddhism. Other books offer more case studies and history, and I have suggested these studies in the further reading section and in the extensive bibliography. In taking this critical and constructive approach I am instigating a conversation on which we can make different conclusions, but the debate – to be engaged in the debate and, in fact, to be able to do so – is the important thing.

In this book I am covering a large number of ideas. This has led me to a certain bias in my selection of material. It also means that I have emphasized locations where engaged Buddhism is practised. There could be much more debate on race and racism, which I clearly talk about from a particular perspective in Chapter 8, particularly related to Buddhist participation in Black Lives Matter. Material has been appearing throughout the summer of 2020 on both Buddhist responses to BLM and to Covid-19. The former will likely have a large body of material over the coming years, while early discussions of the latter can be found on Pierce Salguero’s excellent Jivaka.net, which involves a number of exceptional scholars discussing Buddhist responses to the global pandemic.

The origins of the term ‘engaged Buddhism’

The term ‘engaged Buddhism’ is usually attributed to the Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh. It has become standard to suggest that he coined the term somewhere around 1963.4 Its specific occurrence, however, is not clear.

The term appears to have first been used in a book, published in Vietnamese, called Dao Phat Di Vao Cuoc Doi (1964), which translates as ‘Buddhism entering into society’ or ‘Buddhism entering into life’.5 A list of Thich Nhat Hanh’s books I have received from Plum Village (Thich Nhat Hanh’s community is France) states that Dao Phat Di Vao Cuoc Doi 6 was published in 1964 by La Boi press (Nhat Hanh, 1964). The list states that the title of the book literally means ‘Buddhism entering into society’, and that Thich Nhat Hanh translated this title as ‘Engaged Buddhism’.

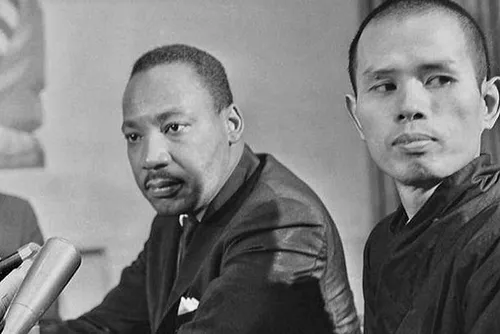

FIGURE 1 Thich Nhat Hanh and Martin Luther King Jr, 31 May 1966, Chicago Sheraton Hotel. Credit: Provenance unknown.

There is an English translation of Dao Phat Di Vao Cuoc Doi (or a version of it) made by Trinh Van Du dated 1965 called Engaged Buddhism (with Other Essays). This would, of course, suggest that Trinh Van Du’s English translation contains the first occurrence of the term engaged Buddhism. The following offers some context:

The phrase engaged Buddhism itself is not satisfactory, because if we analyse it, we will have the feeling that Buddhism is something which is outside life and therefore we need to bring it into life. In reality, it is not so. Buddhism was born right in the lap of life, it has been nourished by it and restored by life. If Buddhism is present in life, is it necessary to bring it into life? [. . .]

Therefore, to engage Buddhism into life means to realize Buddhist principles in life, by methods which are suitable to real situations of life to transform it into a good and beautiful one. Only when Buddhist energies are clearly seen in every form of life, can we be able to say that Buddhism is really present in life. (Nhat Hanh, 1965a: 2)7

In the translation Thich Nhat Hanh also speaks of rebuilding Buddhism, and applying Buddhist principles to spiritual, cultural, economic, artistic and social activities (Nhat Hanh, 1965a: 93).

The first occurrence of the English term ‘engaged Buddhism’ is in Trinh Van Du’s translation, in the form of the title of the book and in its opening pages, published in 1965. However, it is not clear who Trinh Van Du is or was; it is also not known if he coined the term himself, or if it was done in collaboration with Thich Nhat Hanh, or if it was suggested by the latter. What is clear is that Thich Nhat Hanh has favoured the term ‘engaged Buddhism’ as a translation of Dao Phat Di Vao Cuoc Doi in the later years.8

A reasonable timeline for the occurrence of the term engaged Buddhism is the following:

• The concept of ‘Buddhism entering into society’ (Dao Phat Di Vao Cuoc Doi), which is the title of the Vietnamese book published in 1964;

• ‘Engaged Buddhism’ which is the translation of the book written by Trinh Van Du in 1965 that I have just been discussing;

• Thich Nhat Hanh uses the term engaged Buddhism in 1967 (Nhat Hanh, 1967: 52), which is the first time he uses the term in English. (Main and Lai, 2013: 16)

Thich Nhat Hanh spoke about the original Vietnamese book in a public talk in Vietnam in 2008. He first explains how he formulated the idea of engaged Buddhism in a series of ten articles in the 1950s, giving them the title ‘A Fresh Look at Buddhism’. He states that the idea of engaged Buddhism originated in 1954: ‘It is in this series of ten articles that I proposed the idea of Engaged Buddhism—Buddhism in the realm of education, economics, politics, and so on. So Engaged Buddhism dates from 1954’ (Nhat Hanh, 2008a: 30) He describes how, after lecturing in Buddhist studies at Columbia University in 1963–4, he returned home to Vietnam:

So I went home. I founded the Van Hanh University, and I published a book called Engaged Buddhism, a collection of my articles I had written before. [. . .] This is the beginning of 1964. I had written these articles before that, but I put them together and published under the title Engaged Buddhism, or Dao society. Di vao cuoc doi. Cuoc doi here is ‘life’ or ‘society’. Di vao means ‘to enter’. So these were the words that were used for Engaged Buddhism in Vietnam: di vao cuoc doi, ‘entering into life, social life’. (Nhat Hanh, 2008a: 30–1)

The term is also explained by Thich Nhat Hanh:

In Vietnamese we use the phrase Đa.o pha...