eBook - ePub

Sexuality Counseling

Theory, Research, and Practice

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"Sexuality Counseling: Theory, Research, and Practice is an important resource for mental health practitioners. Sexuality is complex and rather than attempting to simplify, this book works within that complexity in a well-organized and comprehensive way."

- Alexandra H. Solomon, Northwestern University

Providing a comprehensive, research- and theory-based approach to sexuality counseling, this accessible and engaging book is grounded in an integrative, multi-level conceptual framework that addresses the various levels at which individuals experience sexuality. At each level (physiological, developmental, psychological, gender identity and sexual orientation, relational, cultural/contextual, and positive sexuality), the authors emphasize practical strategies for assessment and intervention. Interactive features, including case studies, application exercises, ethics discussions, and guided reflection questions, help readers apply and integrate the information as they develop the professional competency needed for effective practice.

- Alexandra H. Solomon, Northwestern University

Providing a comprehensive, research- and theory-based approach to sexuality counseling, this accessible and engaging book is grounded in an integrative, multi-level conceptual framework that addresses the various levels at which individuals experience sexuality. At each level (physiological, developmental, psychological, gender identity and sexual orientation, relational, cultural/contextual, and positive sexuality), the authors emphasize practical strategies for assessment and intervention. Interactive features, including case studies, application exercises, ethics discussions, and guided reflection questions, help readers apply and integrate the information as they develop the professional competency needed for effective practice.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sexuality Counseling by Christine Murray,Amber L. Pope,Ben Willis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Education Counseling. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1 Addressing Sexuality in Professional Counseling

What is sexuality?What is your understanding of sexuality?To what extent does sexuality define people’s lives and intimate relationships?

We would wager a guess that if we asked the questions above to ten people, we would hear ten very different responses. We’ve grown accustomed to the interesting looks and responses we get when we tell people we address the topic of sexuality in our teaching, research, and clinical practice, and the responses were similar when we shared the news with our friends and family that we were writing this book. We need to look no further than these responses to know that sexuality is a topic to which people ascribe a lot of meaning, which gives rise to a range of emotional and attitudinal responses.

We can see the confusion about sexuality at a cultural level as well. On the one hand, sex is virtually everywhere—such as in popular music, advertising, movies, and television. On the other hand, many people are very uncomfortable with even the idea of discussing sex in their most personal relationships, including with their romantic partners and their children. Further, in many geographic areas, there is very limited education about sexuality in school settings (Denehy, 2007). From a family systems perspective, the issue of sex in society is a classic “double bind,” in that there are conflicting social messages of “Have a lot of sex” and “Don’t have sex or at least not unless you are in a committed or marriage relationship,” along with the third message of “Please, please don’t talk about it!”

Despite their professional training, counselors are not immune to the discomfort surrounding sexuality (Binik & Meana, 2009; Harris & Hays, 2008). Training in sexuality counseling is not required for many mental health professionals (Binik & Meana, 2009; Harris & Hays, 2008; Juergens, Smedema, & Berven, 2009; Kazukauskas & Lam, 2009; Miller & Byers, 2010; Southern & Cade, 2011), so unfortunately, many counselors enter their professional careers without having any formal education on how to address sexuality-related issues with their clients. Counselors are, of course, human first and as such, they are products of their social and cultural environments, and therefore often experience a good deal of anxiety discussing sexuality (Juergens, Smedema, & Berven, 2009; Kazukauskas & Lam, 2009; Kleinplatz, 2009; Nasserzadeh, 2009). Even counselors who feel generally comfortable discussing the topic often have certain sexuality-related topics that are more anxiety-provoking than others. And yet, how can counselors expect their clients to be comfortable discussing their sexuality-related concerns when they themselves are not comfortable with these topics?

Clients often seek counseling for concerns related to their sexuality, whether as their primary concern or as a secondary concern to more pressing issues (Miller & Byers, 2010; Southern & Cade, 2011). However, many counselors likely do not view sexuality concerns as being within the scope of their professional identities or competence. In many cases, clients’ sexuality-related concerns are never addressed or are addressed inadequately. The reasons for this may include that their counselors fail to ask about their sexuality-related concerns, that clients do raise the issues but counselors move on prematurely to discussing other concerns, and/or that clients and counselors fumble through discussing these issues at a surface level but fail to address them with enough depth to produce meaningful change.

For all of these reasons, we believe that sexuality is an essential topic for counselors to become competent enough to address in their work. The scope of the topics included in this book demonstrates the broad range of sexuality-related concerns that clients may bring to counseling. We cannot imagine a clinical setting in which counselors would not have the potential to work with clients experiencing sexuality-related concerns. Therefore, we believe that counselors with any and all specialized backgrounds must have at least a basic understanding of how to address sexuality concerns, either themselves or through referrals to other specialized clinicians.

Our goal in this book is to provide readers with an understanding of these concerns, as well as research- and theory-based interventions for addressing them. This first chapter provides the foundation for the remaining chapters, and we begin this chapter by defining sexuality and providing an overview of the aspects of sexuality addressed later in this book. Then, we discuss key professional issues, including credentialing, the history of sexuality counseling and sex therapy, and important professional competencies. Later in the chapter, we introduce the unique ethical context for sexuality counseling. The chapter concludes with an overview of the remainder of the book. After reading this chapter, readers will be able to do the following:

- Describe the Contextualized Sexuality Model

- Understand the historical context surrounding sexuality counseling

- Delineate the distinctions between sexuality counseling and sex therapy

- Discuss key ethical considerations for doing sexuality counseling

Defining Sexuality

One of the most comprehensive and widely cited definitions of sexuality is the following one put forward by the World Health Organization (WHO; World Health Organization, 2010):

Sexuality is “a central aspect of being human throughout life (that) encompasses sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, eroticism, pleasure, intimacy and reproduction. Sexuality is experienced and expressed in thoughts, fantasies, desires, beliefs, attitudes, values, behaviours, practices, roles and relationships. While sexuality can include all of these dimensions, not all of them are always experienced or expressed. Sexuality is influenced by the interaction of biological, psychological, social, economic, political, cultural, legal, historical, religious and spiritual factors.” (p. 4)

This definition shows that sexuality is far broader than many people initially assume. Further, the term sexuality is inclusive of, but not limited to, the physical act of sex and sexual orientation. The WHO (2010) definition of sexuality also emphasizes that sexuality is a very individual aspect of people’s lives. Given all of the varying influences upon sexuality, each and every person expresses his or her sexuality in a unique and personalized manner.

A Comprehensive, Contextual Framework for Understanding Sexuality

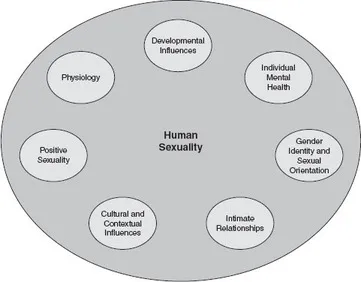

Several scholars advocate for a comprehensive, integrative, multidisciplinary approach to understanding human sexuality (e.g., Bitzer, Platano, Tschudin, & Alder, 2008; Levine, 2009). As such, this book is grounded in the comprehensive, contextual conceptualization of human sexuality that is presented in Figure 1.1. We refer throughout this book to this framework, which we call the Contextualized Sexuality Model, as an organizational framework for understanding the diverse influences on the sexuality-related issues that clients bring to counseling. This model holds that sexuality is a core component of human life, and it is embedded within numerous contextual influences. As shown in Figure 1.1, the contextual influences on human sexuality that will be discussed through the rest of the book include physiology, developmental influences, psychology, gender identity and sexual orientation, intimate relationships, cultural and contextual influences, and positive sexuality. These influences are reciprocal, in that each one impacts a person’s sexuality, and likewise, one’s views of and experiences with sexuality can impact growth and development in the contextual areas.

Figure 1.1 The Contextualized Sexuality Model

Although we depict each contextual influence as an independent entity, the influences are interactive and are combined in unique ways for each person. For example, one’s sexual orientation cannot be understood fully without consideration of such other influences as how that sexual orientation is viewed within the client’s significant cultural and social relationships or how the person expresses his or her sexual orientation within intimate relationships. We developed the Contextualized Sexuality Model to be adaptable to clients’ unique needs and circumstances. We assume that clients will vary in the extent to which each contextual influence is at play in the sexuality-related concerns that they bring to counseling. For example, consider the following three case examples, all depicting scenarios of couples presenting for counseling related to conflict over disparate levels of sexual desire between partners.*

* All case illustrations in this book are fictional and not based on any real individuals. They were imagined to illustrate the points being made in the text.

Although each of these couples in the cases above are presenting for counseling with a similar underlying issue—one partner has a higher level of sexual desire than the other partner—the dynamics of their relationships and concerns in counseling are very different. Although all of the influences in the Contextualized Sexuality Model are likely at play to some degree in each couple’s situation, certain themes are likely to be more prominent for each couple. For Susan and Kent, the most prominent influences are likely the developmental transition to expanding their family, the physiological effects of pregnancy and childbirth for Susan, and the dynamics of their intimate relationship. For Steve and Joanna, Steve’s mental health appears to be a primary influence, as well as likely the physiological impacts of his antidepressant medication. And finally, for Elena and Sophia, their intimate relationship patterns over the past several years are likely interplaying with their views of the importance of sexuality for promoting positive relationships and personal growth as they figure out how to adapt their sexual relationship to their new phase of life in retirement. Of course, if we knew more details about each couple, it is likely that we would find other influences at play as well. Nonetheless, these cases demonstrate how the complexity of clients’ sexuality concerns can be understood best within the broader framework of contextual influences. Before we move on to addressing professional considerations for sexuality counseling, we provide a brief introduction to each of the categories of influences in the Contextualized Sexuality Model.

Physiology

Sex and sexuality have their origins within the body, from the anatomical body parts that determine one’s biological sex, to the physical touching and connections involved in intimacy with another person, and further to the physiological requirements of human reproduction (Althof, 2010; Bitzer et al., 2008; Levine, 2009). Many counselors lack intensive training in biology and anatomy, and therefore, this aspect of sexuality can be intimidating to many counselors and counselors-in-training. Nonetheless, physiological components are essential for understanding human sexuality, and therefore, counselors should equip themselves with a basic understanding of the physiological underpinnings of human sexuality. For example, a counselor working with a female concerned about her ability to become aroused to orgasm would need to understand the basic physiology surrounding female sexual functioning, as well as be comfortable discussing this client’s functioning and attitudes toward that functioning as part of the counseling process.

Developmental Influences

Human sexuality can be viewed as a lifelong process that grows and evolves as people move through various developmental phases in their lives and relationships. Expectations surrounding people’s sexuality often begin even while in the womb—such as through the gender expectations that arise when parents learn their baby’s sex and through comments that people often jokingly make about the possibilities for the baby’s future (e.g., “Someday your daughter can marry my son so we can be family!”). Sexuality in childhood often takes the form of curiosity, exploration, and many, many questions. Parents and educators often struggle with how best to talk with children about their emerging sexuality. Sadly, rates of childhood sexual abuse remain high, and therefore, some children’s experiences with sexuality are impacted by their experiences of abuse.

As individuals progress through adolescence and young adulthood, their emerging sense of themselves as sexual beings continues to evolve as they navigate dating, intimate relationships, and realities about the potential consequences of sexual activities (e.g., sexually transmitted infections [STIs] and unplanned pregnancies). Throughout all of adulthood, people grow and change in their sexuality in unique and individualized ways. Although older adults are often stereotyped as being nonsexual, many adults continue to enjoy a healthy sense of sexuality throughout their entire lives. Overall, then, it is important for sexuality counselors to understand common sexuality-related developmental transitions, challenges, and opportunities that people face and how these impact clients’ concerns in counseling (Althof, 2010).

Individual Mental Health

A person’s overall mental health is closely intertwined with his or her sexuality (Bitzer et al., 2008; Levine, 2009). Sexuality is one avenue through which people express their beliefs, values, feelings about themselves, and body image (Juergens, Smedema, & Berven, 2009). Therefore, one’s sexuality can impact one’s mental health, and one’s mental health can impact one’s sexuality. For example, a client presenting with depressive symptoms may report a loss of interest in sexual activities, and this loss of interest in sex may also bring about anxieties about one’s sexuality and relationships. Indeed, researchers have demonstrated common links between mental health disorders and sexual functioning. In addition, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V; American Psychiatric Association, 2013a) contains sections on sexual dysfunctions and gender dysphoria, and therefore, a category of mental disorders relates directly to sexuality-related concerns. Further, there is growing recognition of the links between addiction and sexuality, including sexually compulsive and addictive behaviors. In addition, the mental health consequences of trauma, whether related to sexual abuse or other forms of trauma, can impact clients’ sexuality. Therefore, individual mental health functioning is an important contextual area for understanding human sexuality.

Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation

Sexuality is undoubtedly impacted by how people view their gender and sexual orientation. Gender identity encompasses not only whether one views him- or herself to be male, female, and/or transgender but also the meanings the person ascribes to that gender role (Juergens, Smedema, & Berven, 2009). Therefore, counselors can make no assumptions about what it means for someone to be a woman, man, or transgender person in society today. Likewise, sexual orientation is a more complicated construct than a categorical view (i.e., straight, gay, lesbian, or bisexual) that this construct implies. For example, Holden and Holden (1995) described the Sexual Identity Profile (SIP), which demonstrates that people’s sexual identities are far more multidimensional than commonly thought. The SIP suggests that people define their sexual identities along five continuums, falling somewhere between homosexual and heterosexual on the following five dimensions: (a) sexual orientation (i.e., toward which sex one is erotically attracted), (b) sexual attitudes (i.e., one’s beliefs about which sexual orientations are acceptable or unacceptable), (c) erotic behaviors (i.e., the sex or sexes with which the person engages in sexual behaviors), (d) public image (i.e., how others perceive one’s sexual orientation), and (e) nonerotic behaviors (i.e., the sex or sexes with which the person uses non-sexual forms of interaction and touch, such as handshakes). Holden and Holden asserted that the ideal profile, meaning the one that would most likely lead the person to feel a sense of congruence about his or her sexual identity, is one in which the person falls at similar points along the first four dimensions and falls near the center along the fifth continuum. In other words, a person with a congruent profile would understand the sex(es) that are erotically attractive, believe that this sexual orientation is acceptable, engage appropriately in sexual behaviors that are consistent with his or her sexual orientation, and be accepted by others as having that sexual orientation, and yet they would feel comfortable interacting and engaging with others regardless of gender. Therefore, it is important for counselors to understand not only the labels that clients ascribe to their gender and sexual orientation but also how their gender identity and sexual orientation fit within the broader social and individual context (Bitzer et al., 2008; Levine, 2009).

Intimate Relationships

Relationship functioning is an important aspect of sexuality (Althof, 2010; Bitzer et al., 2008; Levine, 2009). Sexual activity often occurs within the context of an intimate relationship, and so the health and dynamics of that relationship contribute to how sexual and relationship partners experience sex and sexuality. Common folklore holds that “Sex is the glue that holds partners together,” and also that “Sex is a barometer of how things are in other areas of a couple’s relationship.” Although there may be some truth to these statements for some couples, counselors must set aside the assumptions that they hold about the role of sex in intimate relationships, as clients will vary widely in their sexual attitudes, behaviors, and practices within their relationships. For some couples, sexual intimacy is a primary vehicle for connection, but other couples place a much lower value on physical intimacy and may achieve intimacy in various other ways. Further, some couples cannot engage in sexual behaviors, such as when physical health conditions or disabilities prohibit this form of sexual expression. Relationships can come in many forms, from casual dating relationships to monogamous partners, to marriage and domestic partnerships, to open and polyamorous relationships. The meaning and functions of sexuality within clients’ intimate relationships are important for understanding how clients express and view their sexuality.

Cultural and Contextual Influences

Tiefer (2009) defined sexuality as

a socially construct...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Publisher Note

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Brief Contents

- Detailed Contents

- Series Editors’ Preface

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 Addressing Sexuality in Professional Counseling

- Chapter 2 Assessment in Sexuality Counseling

- Chapter 3 General Interventions and Theoretical Approaches to Sexuality Counseling

- Chapter 4 Physiology and Sexual Health

- Chapter 5 Lifespan Development and Sexuality

- Chapter 6 Sexuality and Mental Health

- Chapter 7 Gender Identity and Affectional/Sexual Orientation

- Chapter 8 Sexuality and Intimate Relationships

- Chapter 9 Cultural and Contextual Influences on Sexuality

- Chapter 10 Positive Sexuality: A New Paradigm for Sexuality Counseling

- Epilogue: From the Author’s Chair

- References

- Index