- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fundamentals of Item Response Theory

About this book

Using familiar concepts from classical measurement methods and basic statistics, Hambleton and colleagues introduce the basics of item response theory (IRT) and explain the application of IRT methods to problems in test construction, identification of potentially biased test items, test equating, and computerized-adaptive testing. The book also includes a thorough discussion of alternative procedures for estimating IRT parameters, such as maximum likelihood estimation, marginal maximum likelihood estimation, and Bayesian estimation in such a way that the reader does not need any knowledge of calculus to follow these explanations. Including step-by-step numerical examples throughout, the book concludes with an exploration of new directions in IRT research and development.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fundamentals of Item Response Theory by Ronald K. Hambleton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Research & Methodology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Background

Consider a typical measurement practitioner. Dr. Testmaker works for a company that specializes in the development and analysis of achievement and aptitude tests. The tests developed by Dr. Testmaker’s company are used in awarding high school diplomas, promoting students from one grade to the next, evaluating the quality of education, identifying workers in need of training, and credentialing practitioners in a wide variety of professions. Dr. Testmaker knows that the company’s clients expect high quality tests, tests that meet their needs and that can stand up technically to legal challenges. Dr. Testmaker refers to the AERA/APA/NCME Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (1985) and is familiar with the details of a number of lawsuits that have arisen because of questions about test quality or test misuse.

Dr. Testmaker’s company uses classical test theory models and methods to address most of its technical problems (e.g., item selection, reliability assessment, test score equating), but recently its clients have been suggesting—and sometimes requiring—that item response theory (IRT) be used with their tests. Dr. Testmaker has only a rudimentary knowledge of item response theory and no previous experience in applying it, and consequently he has many questions, such as the following:

- What IRT models are available, and which model should be used?

- Which of the many available algorithms should be used to estimate parameters?

- Which IRT computer program should be used to analyze the data?

- How can the fit of the chosen IRT model to the test data be determined?

- What is the relationship between test length and the precision of ability estimates?

- How can IRT item statistics be used to construct tests to meet content and technical specifications?

- How can IRT be used to evaluate the statistical consequences of changing items in a test?

- How can IRT be used to assess the relative utility of different tests that are measuring the same ability?

- How can IRT be used to detect the presence of potentially biased test items?

- How can IRT be used to place test item statistics obtained from nonequivalent samples of examinees on a common scale?

The purpose of this book is to provide an introduction to item response theory that will address the above questions and many others. Specifically, it will (a) introduce the basic concepts and most popular models of item response theory, (b) address parameter estimation and available computer programs, (c) demonstrate approaches to assessing model-data fit, (d) describe the scales on which abilities and item characteristics are reported, and (e) describe the application of IRT to test construction, detection of differential item functioning, equating, and adaptive testing. The book is intended to be oriented practically, and numerous examples are presented to highlight selected technical points.

Limitations of Classical Measurement Models

Dr. Testmaker’s clients are turning towards item response theory because classical testing methods and measurement procedures have a number of shortcomings. Perhaps the most important shortcoming is that examinee characteristics and test characteristics cannot be separated: each can be interpreted only in the context of the other. The examinee characteristic we are interested in is the “ability” measured by the test. What do we mean by ability? In the classical test theory framework, the notion of ability is expressed by the true score, which is defined as “the expected value of observed performance on the test of interest.” An examinee’s ability is defined only in terms of a particular test. When the test is “hard,” the examinee will appear to have low ability; when the test is “easy,” the examinee will appear to have higher ability. What do we mean by “hard” and “easy” tests? The difficulty of a test item is defined as “the proportion of examines in a group of interest who answer the item correctly.” Whether an item is hard or easy depends on the ability of the examinees being measured, and the ability of the examinees depends on whether the test items are hard or easy! Item discrimination and test score reliability and validity are also defined in terms of a particular group of examinees. Test and item characteristics change as the examinee context changes, and examinee characteristics change as the test context changes. Hence, it is very difficult to compare examinees who take different tests and very difficult to compare items whose characteristics are obtained using different groups of examinees. (This is not to say that such comparisons are impossible: Measurement specialists have devised procedures to deal with these problems in practice, but the conceptual problem remains.)

Let us look at the practical consequences of item characteristics that depend on the group of examinees from which they are obtained, that is, are group-dependent. Group-dependent item indices are of limited use when constructing tests for examinee populations that are dissimilar to the population of examinees with which the item indices were obtained. This limitation can be a major one for test developers, who often have great difficulty securing examinees for field tests of new instruments—especially examinees who can represent the population for whom the test is intended. Consider, for example, the problem of field-testing items for a state proficiency test administered in the spring of each year. Examinees included in a field test in the fall will, necessarily, be less capable than those examinees tested in the spring. Hence, items will appear more difficult in the field test than they will appear in the spring test administration. A variation on the same problem arises with item banks, which are becoming widely used in test construction. Suppose the goal is to expand the bank by adding a new set of test items along with their item indices. If these new item indices are obtained on a group of examinees different from the groups who took the items already in the bank, the comparability of item indices must be questioned.

What are the consequences of examinee scores that depend on the particular set of items administered, that is, are test-dependent? Clearly, it is difficult to compare examinees who take different tests: The scores on the two tests are on different scales, and no functional relationship exists between the scales. Even if the examinees are given the same or parallel tests, a problem remains. When the examinees are of different ability (i.e., the test is more difficult for one group than for the other), their test scores contain different amounts of error. To demonstrate this point intuitively, consider an examinee who obtains a score of zero: This score tells us that the examinee’s ability is low but provides no information about exactly how low. On the other hand, when an examinee gets some items right and some wrong, the test score contains information about what the examinee can and cannot do, and thus gives a more precise measure of ability. If the test scores for two examinees are not equally precise measures of ability, how may comparisons between the test scores be made? To obtain scores for two examinees that contain equal amounts of error (i.e., scores that are equally reliable), we can match test difficulty with the approximate ability levels of the examinees; yet, when several forms of a test that differ substantially in difficulty are used, test scores are, again, not comparable. Consider two examinees who perform at the 50% level on two tests that differ substantially in difficulty: These examinees cannot be considered equivalent in ability. How different are they? How may two examinees be compared when they receive different scores on tests that differ in difficulty but measure the same ability? These problems are difficult to resolve within the framework of classical measurement theory.

Two more sources of dissatisfaction with classical test theory lie in the definition of reliability and what may be thought of as its conceptual converse, the standard error of measurement. Reliability, in a classical test theory framework, is defined as “the correlation between test scores on parallel forms of a test.” In practice, satisfying the definition of parallel tests is difficult, if not impossible. The various reliability coefficients available provide either lower bound estimates of reliability or reliability estimates with unknown biases (Hambleton & van der Linden, 1982). The problem with the standard error of measurement, which is a function of test score reliability and variance, is that it is assumed to be the same for all examinees. But as pointed out above, scores on any test are unequally precise measures for examinees of different ability. Hence, the assumption of equal errors of measurement for all examinees is implausible (Lord, 1984).

A final limitation of classical test theory is that it is test oriented rather than item oriented. The classical true score model provides no consideration of how examinees respond to a given item. Hence, no basis exists for determining how well a particular examinee might do when confronted with a test item. More specifically, classical test theory does not enable us to make predictions about how an individual or a group of examinees will perform on a given item. Such questions as, What is the probability of an examinee answering a given item correctly? are important in a number of testing applications. Such information is necessary, for example, if a test designer wants to predict test score characteristics for one or more populations of examinees or to design tests with particular characteristics for certain populations of examinees. For example, a test intended to discriminate well among scholarship candidates may be desired.

In addition to the limitations mentioned above, classical measurement models and procedures have provided less-than-ideal solutions to many testing problems—for example, the design of tests (Lord, 1980), the identification of biased items (Lord, 1980), adaptive testing (Weiss, 1983), and the equating of test scores (Cook & Eignor, 1983, 1989).

For these reasons, psychometricians have sought alternative theories and models of mental measurement. The desirable features of an alternative test theory would include (a) item characteristics that are not group-dependent, (b) scores describing examinee proficiency that are not test-dependent, (c) a model that is expressed at the item level rather than at the test level, (d) a model that does not require strictly parallel tests for assessing reliability, and (e) a model that provides a measure of precision for each ability score. It has been shown that these features can be obtained within the framework of an alternative test theory known as item response theory (Hambleton, 1983; Hambleton & Swaminathan, 1985; Lord, 1980; Wright & Stone, 1979).

Exercises for Chapter 1

1.Identify four of the limitations of classical test theory that have stimulated measurement specialists to pursue alternative measurement models.

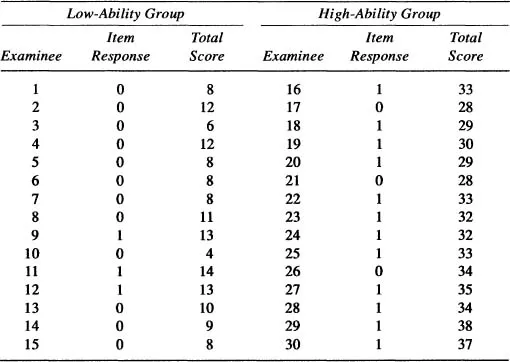

2.Item responses on a test item and total test scores for 30 examinees are given in Table 1.1. The first 15 examinees were classified as “low ability” based on their total scores; the second 15 examinees were classified as “high ability.”

a.Calculate the proportion of examinees in each group who answered the item correctly (this is the classical item difficulty index in each group).

b.Compute the item-total correlation in each group (this is the classical item discrimination index in each group).

c.What can you conclude regarding the invariance of the classical item indices?

TABLE 1.1

Answers to Exercises for Chapter 1

1.Item-dependent ability scores, sample-dependent item statistics, no probability information available about how examinees of specific abilities might perform on certain test items, restriction of equal measurement errors for all examinees.

2.a.Low-scoring group: p = 0.2. High-scoring group: p = 0.8.

b.Low-scoring group: r = 0.68. High-scoring group: r = 0.39.

c.Classical item indices are not invariant across subpopulations.

2

Concepts, Models, and Features

Basic Ideas

Item response theory (IRT) rests on two basic postulates: (a) The performance of an examinee on a test item can be predicted (or explained) by a set of factors called traits, latent traits, or abilities; and (b) the relationship between examinees’ item performance and the set of traits underlying item performance can be described by a monotonically increasing function called an item characteristic function or item characteristic curve (ICC). This function specifies that as the level of the trait increase...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Series Editor’s Foreword

- Preface

- 1. Background

- 2. Concepts, Models, and Features

- 3. Ability and Item Parameter Estimation

- 4. Assessment of Model-Data Fit

- 5. The Ability Scale

- 6. Item and Test Information and Efficiency Functions

- 7. Test Construction

- 8. Identification of Potentially Biased Test Items

- 9. Test Score Equating

- 10. Computerized Adaptive Testing

- 11. Future Directions of Item Response Theory

- Appendix A: Classical and IRT Parameter Estimates for the New Mexico State Proficiency Exam

- Appendix B: Sources for IRT Computer Programs

- References

- Index

- About the Authors