eBook - ePub

Organized Crime

Analyzing Illegal Activities, Criminal Structures, and Extra-legal Governance

- 488 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Organized Crime

Analyzing Illegal Activities, Criminal Structures, and Extra-legal Governance

About this book

2016 Outstanding Publication Award (The International Association for the Study of Organized Crime)

Organized Crime: Analyzing Illegal Activities, Criminal Structures, and Extra-legal Governance provides a systematic overview of the processes and structures commonly labeled "organized crime," drawing on the pertinent empirical and theoretical literature primarily from North America, Europe, and Australia. The main emphasis is placed on a comprehensive classificatory scheme that highlights underlying patterns and dynamics, rather than particular historical manifestations of organized crime. Esteemed author Klaus von Lampe strategically breaks the book down into three key dimensions: (1) illegal activities, (2) patterns of interpersonal relations that are directly or indirectly supporting these illegal activities, and (3) overarching illegal power structures that regulate and control these illegal activities and also extend their influence into the legal spheres of society. Within this framework, numerous case studies and topical issues from a variety of countries illustrate meaningful application of the conceptual and theoretical discussion.

Organized Crime: Analyzing Illegal Activities, Criminal Structures, and Extra-legal Governance provides a systematic overview of the processes and structures commonly labeled "organized crime," drawing on the pertinent empirical and theoretical literature primarily from North America, Europe, and Australia. The main emphasis is placed on a comprehensive classificatory scheme that highlights underlying patterns and dynamics, rather than particular historical manifestations of organized crime. Esteemed author Klaus von Lampe strategically breaks the book down into three key dimensions: (1) illegal activities, (2) patterns of interpersonal relations that are directly or indirectly supporting these illegal activities, and (3) overarching illegal power structures that regulate and control these illegal activities and also extend their influence into the legal spheres of society. Within this framework, numerous case studies and topical issues from a variety of countries illustrate meaningful application of the conceptual and theoretical discussion.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Organized Crime by Klaus von Lampe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Criminology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I Organized Crime as a Construct and as an Object of Study

Chapter 1 Introduction—The Study of Organized Crime

The study of organized crime encompasses the examination of a broad range of phenomena. In a nutshell, researchers try to find out three things:

- How and why crimes such as, for example, drug trafficking or serial burglary are committed

- How and why criminals are connected and organized in networks, gangs, syndicates, cartels, and mafias

- How and why criminals acquire power and use this power to control other criminals and to gain influence over aspects of legitimate society, namely business and politics

This book discusses answers to these questions within a general conceptual framework that is not tied to any particular case, country, or historical period. The ambition is to provide readers with the analytical tools necessary to come to a sound assessment of phenomena irrespective of when or where they may manifest themselves. While the book is global in scope, most of the referenced literature has been published in English by European, North American, and Australian authors. Accordingly, the discussion is somewhat narrowed to the phenomena that these authors have examined, which unfortunately leaves some parts of the world not receiving the level of attention that they deserve.

Phenomena Associated With Organized Crime

The term organized crime is not used consistently. When people speak of organized crime they have different things in mind. And even when they think of the same phenomena, they may have different ideas about what it is that makes organized crime distinct: Is it the organization of crime, the organization of criminals, or the exercise of power by criminals?

The Organization of Crime

Much of what is commonly associated with the term organized crime has to do with the provision of illegal goods and services. Certain goods and services are prohibited (e.g., child pornography), so strictly regulated (e.g., drugs), or so highly taxed (e.g., cigarettes) that suppliers and consumers seek ways to circumvent the law. Arguably the drug trade is currently the main problem of this kind globally. There are few if any countries in the world today that are not in some way or other affected by the production, smuggling, and distribution of substances, such as cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine. Other crime problems of a global dimension are, for example, the trafficking in humans for sexual exploitation and for labor exploitation, illegal arms trafficking, and the trafficking in counterfeit luxury goods and pharmaceuticals. All of these illegal markets change over time. Some laws that criminalize certain products or behaviors are repealed while new products and behaviors are outlawed. Famously, the production and sale of alcohol, including beer and wine, was illegal in the United States during the Prohibition Era, from 1920 until 1933. Gambling, considered the main line of business of organized criminals in the United States in the 1940s through the 1970s, has likewise seen a shift from criminalization toward legalization. The urban poor, who once placed bets on daily numbers with an illegal lottery in their neighborhood, now buy tickets from state-run lotteries. Prostitution, a crime in most of the United States, has only recently been decriminalized in some countries (e.g., Germany) while new criminal laws against prostitution, targeting customers rather than prostitutes, have been passed at about the same time in other countries (e.g., Sweden). Consumer preferences follow the ebbs and flows of fashion, shifting, for example, between different kinds of illegal drugs. The successes and failures of law enforcement shape illegal markets in their own way. For example, the successful interception of marijuana smuggled from Colombia to the United States in the 1970s promoted a shift to the smuggling of a far less bulky illegal substance: cocaine.

Organized crime is not only associated with the supply of illegal goods and services but also with predatory crimes, such as theft, robbery, and fraud. In fact, when the term organized crime first came in use in the mid-1800s in colonial India, it referred primarily to gangs of highway robbers. Likewise, the first consistent use of the term organized crime in the United States around the year 1920 was linked to theft and robbery much more than to illegal gambling or, for that matter, the illegal sale of alcohol (see Chapter 2).

All of these illegal activities, be they centered on supplying willing customers or harming innocent victims, have in common that they can be carried out in a more or less “organized” fashion. Organized in this context means that crimes are committed on a continuous basis involving planning and preparation as opposed to impulsive, spur-of-the moment criminal acts. Organized can also mean that a crime is not a simple, one-dimensional act, like the snatching of a purse, but an endeavor that requires the coordinated completion of interlocking tasks. For example, the trafficking in stolen motor vehicles may involve the combination of such tasks as overriding the car-door lock with a special tool, manipulating the board computer of the car using illegally obtained servicing software, replacing identifying marks on the car, and forging the accompanying documents (see Chapter 5).

Image 1.1 A large clandestine laboratory for the production of methamphetamine discovered at a ranch near Guadalajara in Mexico in May 2011. Authorities found 1,000 kg of crystal meth and hundreds of bags of sodium hydroxide, a chemical used for the production of methamphetamine.

Photo: ©STRINGER/MEXICO/Reuters/Corbis

The organization of crime does not necessarily imply that more than one offender is involved. But the cooperation of several criminals will tend to make the commission of crimes easier as the scale and complexity of an operation increases. Simply put, four or five persons can rework a stolen car or unload contraband from a 40-foot container much quicker than a single person. Likewise, a group of four or five criminals is more likely than any individual criminal to combine the skills, expertise, and capital necessary to steal a car and to change it into a seemingly legitimate car or to set up an investment-fraud business or an illegal drug laboratory. This is one of the reasons why not only crimes but also criminals are organized.

The Organization of Criminals

A law-abiding citizen who fantasizes about committing a crime will likely envision him- or herself acting alone in complete secrecy, without letting anyone in on the crime and, accordingly, without being able to draw on the help and support of anyone. The world of crime that the term organized crime relates to is quite different from this image of a lone offender. The world of organized crime is populated by criminals who know other criminals, who socialize with other criminals, who commit crimes with other criminals, and who quarrel with other criminals. Above and beyond that, these criminals may well be known as such in their communities. The term organized crime conjures up images of gangsters like Al Capone, who are public figures, who hold respect because of the wealth and power they have accumulated from crime. Often the problem for law enforcement is not to find out who the organized criminals are but to link them to specific, indictable offenses.

One of the main challenges in the study of organized crime is to sort through the myriad social relations of criminals and to understand how these relations influence and shape criminal behavior. What may be most readily associated with the organization of criminals are criminal groups that are centered on the commission of particular crimes. A classic example is that of the “working groups” of pickpockets and con artists described by criminologist Edwin Sutherland (1937) in his book The Professional Thief. A working group of, for example, pickpockets, comprises perhaps two to four members who collaborate according to their individual abilities. Some of these groups disband quickly; others continue to exist for many years. And there may be some fluctuation in membership, with some criminals constantly moving from one group to the next.

Image 1.2 Two pickpockets in action in early 19th century London. After C. Williams, scene in St. Paul’s Churchyard.

Photo: © Heritage Corbis

Another now classic example of working groups of criminals is that of the Colombian drug trafficking organizations that dominated the global cocaine trade in the 1980s and early 1990s. A handful of organizations, each with about 100 to 200 full-time employees, managed much of the processing of cocaine in clandestine laboratories and the smuggling of the cocaine from Latin America to markets in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere. Some organizations had set up “cells” within destination countries, namely, in the United States, to also handle the wholesale distribution of the cocaine. Under the leadership of notorious kingpins like Carlos Lehder and Pablo Escobar in Medellin and the Rodriguez Orejuela brothers in Cali, these organizations had quite elaborate internal structures with separate branches for handling specialized tasks apart from the core functions of drug trafficking, including security, counterintelligence on state anti-drug efforts, and the laundering of drug profits. In many instances, the large drug trafficking organizations drew on a host of smaller groups and freelancers on a regular or ad hoc basis to transport precursor chemicals and drugs, launder money, or to carry out contract killings (Kenney, 1999a; Zabludoff, 1997).

Professional thieves, drug traffickers, as well as other criminals form and join working groups essentially to make money, and, as Sutherland (1937, p. 28) points out, they may not even speak socially to one another. Apart from these businesslike, crime-focused criminal groups, criminals are connected in other ways that have more to do with social aspects, with crime as a lifestyle, and less with crime as a profession. There is, first of all, what is commonly referred to as the underworld, an often idealized criminal subculture with its own rules and its own slang, a community of criminals separated from mainstream society, although many links to the upperworld may exist. The underworld is a historical phenomenon that is closely linked to urbanization and to the lower-class quarters of large cities like Berlin, London, or Shanghai (Hobbs, 2013). The underworld materializes in the bars, clubs, and other hangouts where criminals meet, socialize, and gossip. It is here that criminals receive advice, recognition, and support, and it is here that they find accomplices and hatch their plots (McIntosh, 1975, p. 24). Not just anyone who commits crimes is automatically part of the underworld. One has to be accepted as a more or less capable and trustworthy criminal (Fordham, 1972, p. 23). The underworld as a subculture of hundreds, thousands, or even tens of thousands of criminals has no formal structure, yet what has often been described is an informal status hierarchy. Some criminals garner more respect than others because of their personality, skills, or wealth; because of their notoriety in the media; or because of their connections to even more influential persons in the underworld and in the upperworld. Lower-status criminals tend to cluster around these higher-status criminals for support and protection and to increase their own standing within the underworld (see, e.g., Albini, 1971; McIntosh, 1975; Rebscher & Vahlenkamp, 1988).

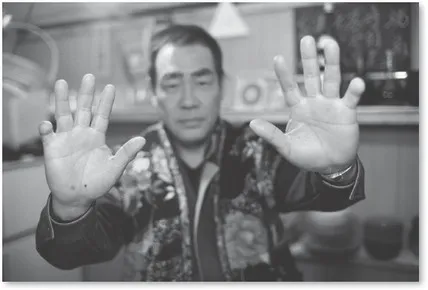

Image 1.3 Yakuza is a generic term for an assortment of Japanese criminal associations that are independent but share the same subcultural norms and values. In this 1993 picture a Yakuza member shows his hands with two fingers cut off. The practice of amputating fingers, called yubitsume, can be a form of punishment or a way to show atonement for wrongdoing in hope of avoiding more severe punishment. Yubitsume may also serve as a demonstration of one’s sincerity in settling a dispute (Hill, 2003, pp. 74–75).

Photo: TWPhoto/Corbis

There are other, much more cohesive and more formalized amalgamations of criminals than the rather amorphous urban underworlds: the clannish criminal fraternities that are at the very center of the mythology surrounding the subject of organized crime, organizations like the Sicilian Mafia, the Calabrese ‘Ndrangheta, the Neapolitan Camorra, the North American Cosa Nostra, the Chinese triads, the Japanese yakuza groups, or the post-Soviet Thieves in Law. All of these groups have their own rituals, symbols, and ideologies, and they have been in existence over many generations. Some trace their history back to medieval times. Sicilian mafiosi, for example, see their origins in an uprising against foreign oppressors in the 13th century (Arlacchi, 1993), and the yakuza place themselves in the tradition of Japan’s ancient warrior class of the samurai (Hill, 2003). By their own accounts and in the perception of others, these organizations constitute criminal elites. Being accepted into their ranks is what many criminals strive for and what may carry with it an enormous boost in prestige and power. That the myth and reality of these criminal organizations do not always match is a different matter.

The Exercise of Power by Criminals

Criminal fraternities like the Sicilian Mafia or the North American Cosa Nostra can be found in a role other than that of just inwardly looking clannish, secretive combinations of criminals. One meaning of the term organized crime is that crime in a specific area is under the control of a particular group of criminals, such as a branch of the Sicilian Mafia or of the North American Cosa Nostra. In a situation like this, criminals are not free to commit any crime. They ne...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Acknowledgements

- Publisher Note

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Part I Organized Crime as a Construct and as an Object of Study

- Chapter 1 Introduction—The Study of Organized Crime

- Chapter 2 The Concept of Organized Crime

- Chapter 3 Organized Crime Research

- Part II Empirical Manifestations of Organized Crime

- Chapter 4 Organized Criminal Activities

- Chapter 5 Criminal Structures—An Overview

- Chapter 6 Illegal Entrepreneurial Structures

- Chapter 7 Associational Structures

- Chapter 8 Illegal-Market Monopolies and Quasi-Governmental Structures

- Part III Organized Crime and Society

- Chapter 9 The Social Embeddedness of Organized Crime

- Chapter 10 Organized Crime and Legitimate Business

- Chapter 11 Organized Crime and Government

- Chapter 12 Transnational Organized Crime

- Part IV The Big Picture and the Arsenal of Countermeasures

- Chapter 13 The Big Picture of Organized Crime

- Chapter 14 Countermeasures Against Organized Crime

- References

- Index