- 392 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Skills for Helping Professionals

About this book

Written specifically for non-clinical undergraduate students, but also relevant to graduate studies in helping professions, Skills for Helping Professionals, by Anne M. Geroski focuses on helping students develop the skills they need to effectively initiate and maintain helping relationships. After exploring the literature identifying critical components of helping relationships and briefly reviewing developmental and helping theories, the text covers such topics as the helping process, self-awareness, and ethics in helping, and then focuses on specific helping skills such as listening and hearing, empathy, reflecting, paraphrasing, questioning, clarifying, exploring, and offering feedback, encouragement, and psycho-education. The final chapters focus on individuals in crisis and helping in groups.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1 Helping Processes

Learning Objectives

- Learn about various professional helping roles

- Understand the differences between helping, counseling, therapy, and advocacy

- Understand, very generally, what is helpful when working with others

Introduction

Welcome to the world of professional helpers!

If you are reading this book, it is probably because you have an interest in working with others, even if you are not sure exactly what that might look like in the future. In this chapter, we will discuss various types of helping professions and review what the literature teaches us about what is helpful in working with others.

Helping Terms: Helping, Counseling, Psychotherapy, Therapy, and Advocacy

Helping

When we use the word helping as a noun, one definition is “a portion or serving of food.” Of course, in this book, we are not really interested in talking about food! Here we are looking to understand the word helping used as a verb, when it is used as an action that is aimed toward others. Permit me to borrow the reference to food as a metaphor for what helping is, though, because ironically, the food metaphor is oddly fitting here, too. Food is the substance that enables us to grow. And helping is that which we give to others so that they may grow. Helping is the effort that we make to offer strength and support to people who want to learn, change, and grow, or who need something when times are hard. Helping is the plate of food that we lay before others to fortify them, offer nourishment, and help them feel cared for.

Counseling, Psychotherapy, and Therapy

Within the category of “helpers” exists an expansive array of clinical and nonclinical roles and professions. Clinical helpers are those who have received advanced level training (master's or doctoral degrees), typically including extensive supervised clinical practice experience, to offer therapeutic interventions for people who struggle with personal or interpersonal difficulties or mental health challenges. Examples of clinical helpers include mental health counselors, marriage and family therapists, psychologists, psychiatrists, and clinical social workers. While nonclinical helpers may also work in the area of mental health providing adjunct care, support, or instruction, they typically have a bachelor's level educational degree, and their work is under the close supervision of a clinical mental health professional. Job titles for these non-clinical positions include counselor, advocate, and therapy assistant. Nonclinical helpers may work in a variety of other settings, too, providing, for example, career guidance, nutrition counseling, exercise coaching, education, assisting with a multitude of daily living tasks, etc. Nonclinical helpers also occupy a vast variety of roles in the medical field. These latter positions may require advanced-level educational training or degrees. A list of many of these varied roles is included in Appendix A.

There is much confusion regarding the terms counseling and psychotherapy. You may notice that in some settings, they are used somewhat interchangeably, yet in other settings they have clear and distinct meanings. For example, a lawyer provides legal counsel, which is obviously very different from the counseling services provided by a mental health counselor. Most of us know not to go to a lawyer for therapeutic intervention regarding our mental health concerns, and not to seek mental health counseling for legal advice. Lawyers, then, are nonclinical professional helpers, and they have advanced degrees and training in the law and legal practice.

In this text, we will use the term counseling in reference to a helping practice that it conducted by clinical and nonclinical helpers and is aimed at assisting others with personal, social, or psychological issues or concerns. As mentioned, the distinction between clinical and nonclinical counseling has to do with training level and scope of practice. Psychotherapy typically refers to a mental health clinical practice, and therapy is just a shorted version of the word psychotherapy. So, clinical counseling and psychotherapy are two terms with virtually the same meaning and are often used interchangeably (Sommers-Flanagan & Sommers-Flanagan, 2004).

The work of counselors and psychotherapists has to do with symptom remission and improved everyday functioning (Lambert, 2013). They help people cope with interpersonal and mental health difficulties such as those posed by addictions, trauma, mental illness, experiences of stress, and difficulties in adjustment. They also help people develop healthy interpersonal relationships, which sometimes includes thinking about situations differently, developing better communication skills, or behaving in different ways. Additionally, counselors and psychotherapists work with individuals in decision-making for the present and future or developing healthy lifestyles, and they provide support for people experiencing crisis or challenges in their lives. The work of counselors and psychotherapists is based on training in psychology and human development theories, such as those discussed in Chapter 2, and also on practice theories such as those reviewed in Chapter 3. A list and descriptions of various clinical and nonclinical helping positions is included in Appendix A.

Advocacy

When we are witness to the adverse effects of social forces such as prejudice and discrimination (in all of their overt and subtle forms) that lead to problematic institutional practices and barriers in the lives of the people we serve, intervention should focus on those sources of problems rather than on the individual. What sets advocacy apart from counseling and psychotherapy, then, is that advocacy attempts to change variables that sit outside the individual—systems and institutions that hamper people in various ways (Funk, Minoletti, Drew, Taylor, & Saraceno, 2005; Lewis, Lewis, Daniels, and D'Andrea, 1998). Advocates are helpers who work with and/or on behalf of people or groups for a particular cause or policy, and the implicit goal of most advocacy efforts is to increase peoples’ sense of personal power or agency. Of course, advocacy is not limited to issues related to mental health. It is relevant in many other fields as well. There are patient advocates in hospitals, child advocates in court systems, advocates for individuals who have disabilities, etc. More about advocacy as a helping intervention is included in Chapter 8.

Helping Relationships

Being helpful generally refers to doing something for others. Synonyms for helping relationships might include being accessible, supportive, benevolent, useful, and working for the benefit of others.

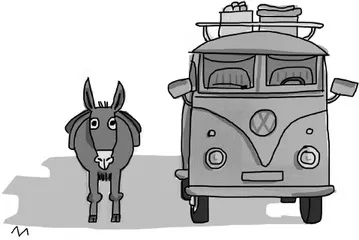

Illustration 1.1 The Helping Relationship

Kim Murton

Illustration 1.1 is interesting, but you are probably wondering what it has to do with helpfulness. I would like to propose that it captures the essence of professional helping relationships. Really! Notice in this illustration that despite their obvious differences, the donkey and the van are traveling together. They are traveling in the same direction, side by side. If we were to think of the van as the helper, we can imagine that it has the potential to offer shade to the donkey if the journey becomes too hot or bright. Also, the van looks like it might be used for camping, with a mini fridge, stove, and storage capacity, and thus we can imagine that it might have a cache of food and water inside. So, this helper van is in the position to offer nourishment and sustainability to the donkey, if needed. We are also aware that while the van could probably travel much quicker than the donkey, it doesn't. They travel side by side. The van doesn't stir up a lot of dust, doesn't run the donkey off the road, and doesn't hurt the donkey by running it over—it travels respectfully at the pace of the donkey. As a metaphor for the helping relationship, then, we see a journey among two who are very different. Yet the journey is shared, with one in the position of walking forward toward the goal and the other, of offering comfort and nourishment as needed along the way.

The Contract

Illustration 1.2 A Contractual Relationship

©iStockphoto.com/

It is important to distinguish helping relationships from the other types of relationships that we all have in our lives. The journey of helping is not the same journey as friendship, even though many of the qualities of being a good friend are also qualities of being a good helper. The helping relationship is best thought of as a contractual relationship where one is in the role of providing goods to someone who has requested them. In fact, in many professional helping relationships, helpees are called clients—the person for whom professional services are rendered. This term emphasizes the idea that the recipient of services is a consumer who receives services in exchange for some kind of payment. An important marker of helping relationships, then, is the helping contract. This alone makes it different from the other relationships we have in our lives. All of the components of the helping contract discussed here are outined in Table 1.1.

Like contracts in other settings, helping contracts contain agreements about the exchange of services and compensation that will be a part of the helping relationship. As Illustration 1.2 suggests, these may be formal or informal, and explicit or implicit. For example, if you are working as a residence hall advisor, you have been hired to supervise students in the dorm—that is the contract you are working under. As part of this contract, your role is to be available to help students when they have questions, are in trouble, or seem to be struggling with something. Your role is also to protect the premises and enforce the residence hall rules. You will probably be required to post hours so the students will know when you are available, talk to all of the residents about the dorm rules, and maybe also plan a certain number of social activities throughout the year. Also part of this contract is the compensation you will receive for your work. This may be in the form of a tuition waiver, a salary stipend, or perhaps it includes a meal plan and a nice room to live in. All of these agreements are made explicitly and in advance so that everyone is clear about your role within this helping relationship. They form an explicit helping contract. For another example, let us say that you have offered to be a volunteer “friend” for a new refugee family in the community. This helping relationship is far more informal, with the details of the support you will provide to be worked out with the family, depending on their changing needs over time. This latter helping relationship has an implied helping contract, however informal it may be, because your contact and role with the family is to provide services or assistance that they may need. Because of this, it is not the same as a friendship, even if it grows and feels like one, even if you call yourself a “family friend.”

A defining component of the helping contract that is evident in the above examples is the concept of nonmutuality. Unlike other relationships, the focus of the helping relationship is always on the needs of the helpee. This is not to say that you, personally, do not have any needs. Nor is it to say that you may not benefit from the relationship in some way (such as payment or satisfaction). What nonmutuality does mean is that the sole focus of the work and all of decision-making must be based on the interests and needs of the helpee. And this, then, is the substance of the helping contract. For example, as a victim advocate in a rape crisis phone hot line, you will not be talking to callers about your own trauma experiences. A customer service representative in a department store will not be talking on his personal phone when a customer is present. A counselor sitting in the room with a client is not daydreaming about what she will be doing after work. And none of these helpers should be engaged in making plans with the helpee to go to a coffee shop to further discuss the issue at hand. The helping relationship is not a mutual relationship.

While it is important for helpers to have a professional level of emotional investment in the helping relationship, this investment comes with restrictions. These restrictions include prohibitions against intimacy, mutual friendship, and physical contact. These will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 4 in the discussion of helping ethics, and alluded to again in Chapter 5, where the discussion focuses on helper self awareness and competence. What is most important here is that the conditions of the helping contract outline the parameters of the helping ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Publisher Note

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Detailed Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Chapter 1 Helping Processes

- Chapter 2 Understanding Development: Theories, Social Context, and Neuroscience

- Chapter 3 Helping Theories for Working with Others

- Chapter 4 Ethical Principles for Helping Relationships

- Chapter 5 Self-Awareness, Cultural Awareness, and Helper Competence

- Chapter 6 Setting the Stage for Helping

- Chapter 7 Listening and Basic Responding Skills in Helping Conversations

- Chapter 8 Skills for Promoting Change

- Chapter 9 Helping People in Crisis

- Chapter 10 Helping in Groups

- Appendix A: Clinical, Nonclinical, and Other Helping Roles

- Appendix B: Helping Professional Organizations

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Skills for Helping Professionals by Anne M. Geroski in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Education Counseling. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.