- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Policy Analysis for Social Workers

About this book

Policy Analysis for Social Workers offers a comprehensive, step-by-step guide to understanding the process of policy development and analysis for effective advocacy. This user-friendly model helps students get excited about understanding policy as a product, a process, and as performance—a unique "3-P" approach to policy analysis as competing texts often just focus on one of these areas. Author Richard K Caputo efficiently teaches the purpose of policy and its relation to social work values, discusses the field of policy studies and the various kinds of analysis, and highlights the necessary criteria (effectiveness, efficiency, equity, political feasibility, social acceptability, administrative, and technical feasibility) for evaluating public policy.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1 Science, Values, and Policy Analysis

This chapter discusses postmodern challenges to the scientific ethos and the implications for social workers seeking to undertake policy analysis in a credible, constructive, and critical manner. The chapter also distinguishes value neutrality from value relevance in the social sciences and shows how impartial or objective analysis of relevant issues germane to social workers and other helping professionals is both desirable and possible. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the role of critical thinking in social work practice and policy analysis.

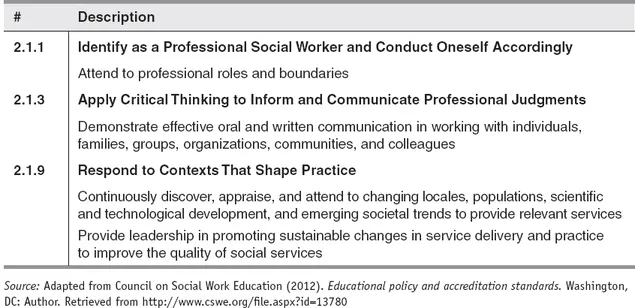

Upon successful completion of the skill building exercises of Chapter 1, students will have mastered the following Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) competencies and practice behaviors:

Source: Adapted from Council on Social Work Education (2012). Educational policy and accreditation standards. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://www.cswe.org/file.aspx?id=13780

The Postmodern Challenge

An explicit concern of this section of Chapter 1 is the postmodern challenge to the scientific ethos and its implications for social workers seeking to undertake policy analysis while maintaining their professional integrity. A related implicit concern of this section and the chapter as a whole is the longstanding observation that reliance on policy experts by policymakers presents a formidable challenge to democratic governance (Collins & Evans, 2007; Dewey, 1927/1954; Fischer, 1991; Lovett, 1927; Moynihan, 1965; Westbrook, 1991). Given the profession's commitment to social justice, it behooves social workers seeking to conduct policy analysis as part of their professional practice to understand dilemmas associated with both concerns so as to take appropriate steps to resolve them accordingly.

Postmodernist thought is not of one piece and it may be past its prime of influence: it has been written about as a period, strategy, mindset, ambience, paradigm, and style, despite denials or evasions by intellectuals such as Foucault, Baudrillard, and Latour (Mathewman & Hoey, 2006). Nonetheless, postmodernism focuses scholarly and public attention on a common set of contemporary concerns that pose major dilemmas for social workers and social scientists in general and for social policy analysts in particular; that is, can the human mind and social knowledge be relied on to give truthful accounts of the world, whether about anything (the wholesale version) or about some things (the selective version), conceding truth to descriptive claims including mathematical ones while denying it to “evaluative” or moral, ethical, interpretive, or ethical ones (Dworkin, 1996; Olkowski, 2012; Rosenau, 1992). If so, as some postmodernists have argued (e.g., Rorty, 1981), many different stories, each a political act, eclipsed the idea of one single truth and called into question the possibility of objective, value-neutral, or impartial social science. As posed by Cravens (2004), the question becomes: “If there were no longer faith in authoritative expertise but faith in all experts, no matter how credulous their claims might be, then of what use was social science [and by extension policy analysis] in the first instance?” (p. 133). Taylor-Gooby (1994) put the issue this way: “if nothing can be said with certainty, it is perhaps better to say nothing” (p. 393). This suggests that an absence of an agreed-upon method of selecting among competing alternative claims might result in no society-wide policy actions at all.

In addition, the postmodern claim that certain themes of modern society (the nation-state, rational planning by government, and large-scale public or private sector bureaucracy) are obsolete challenges theories of social policy that stress such themes as inequality or privilege and for the practice of social policy that relies on rational analysis to inform policymakers and implementers of social provisions (Taylor-Gooby, 1994). Most social workers are not professionally trained as social scientists. Nonetheless, the knowledge base of social work practice is informed by social scientific theories of human behavior and the social environment, and social workers use methods and procedures gleaned from the social sciences when assessing need, deliberating about the appropriateness of policy options, and evaluating their practice (Hart, 1978). Given the profession's commitment to social justice, the challenges posed by reliance on experts and postmodern thought suggest the need for developing and promoting the idea that participatory policy analysis become a more mainstream component of the policy sciences and analyses than is currently the case, while concomitantly balancing professional mandates for impartiality, objectivity, and advocacy as integral components of social work practice (Benveniste, 1984; Brunner, 1991; Fischer 1993; Hampton, 2004; Haynes & Mickelson, 2010; Hernandez, 2008; Meyer, 2008; Schram, 1993; Thompson, 2001).

A key consideration is how to resolve an inherent tension between what Collins and Evans (2007) view on the one hand as the Problem of Legitimacy—that is, how to introduce innovations in social welfare provisioning in the face of widespread distrust or lack of trust in science and in government to address social problems; how to ensure that analysts' views are not influenced by pressure from their principals or clients or by conflicts of personal interests—and on the other hand the Problem of Extension—that is, knowing when and how to limit increased public participation in the policymaking process. In addition, the postmodern challenge to universal claims (egalitarianism, humanism, liberal democracy) suggests that social workers have a responsibility to contribute to the development of appropriate conceptual and analytical skills to discern when such claims serve as an ideological smokescreen, preventing recognition of trends of some of the most important social problems in modern society such as increasing income inequality (Alderson, Beckfield, & Nielsen, 2005; Rosenau, 1992; Taylor-Gooby, 1994).

Case in Point 1.1: ACA and Health Insurance Coverage of Contraceptives

Think of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (P.L. 111–148, hereafter ACA) passed during the Obama administration's first term in office and the subsequent bill (H.R. 45), introduced in the first session of the 113th Congress, to repeal it. Part of the opposition to the ACA stemmed from those who contend that the new law exemplifies government overreach by infringing on individual liberty: ACA, they contend, forces individuals to purchase health insurance, some of whom may not want to do so. Catholic bishops as a group have opposed a regulation emanating from the law requiring health insurance coverage of contraceptives. The Obama administration proposed that churches and nonprofit religious groups that object to providing birth control coverage on religious grounds would not have to cover or pay for it. Women who work for such organizations could get free contraceptive coverage through separate individual health insurance policies, costs to be incurred by the insurance company, with the rationale that the health insurance company could recoup the costs through lower health care expenses resulting in part from fewer births. The Obama administration refused to grant an exemption or accommodation to secular businesses owned by people who said they objected to contraceptive coverage on religious grounds (Pear, 2013). As you think about the general libertarian objections to ACA and the Catholic bishops' objections to the contraceptive mandate, assess the extent to which such appeals to individual liberty and religious freedom, respectively, are ideological smokescreens to thwart the public interest—namely, as Jean Bucaria (2013), the deputy director of NOW-N.Y.C put it, the “health and individual liberties of the vast majority of American women who will use birth control at some point in their lives.” Alternatively, to what extent might Bucaria's appeal to women's rights be a smokescreen to thwart religious freedom or individual liberty as understood by the Catholic bishops and libertarians, respectively?

The approach taken in this chapter and throughout the remainder of the book is in line with Kitcher (1993), who rejected the views of both the logical positivists—who glorify science as conforming to otherworldly standards of purity and rigor—and those contemporary philosophers who reject any idea of scientific truth and condemn scientists for not living up to such standards (Papineau, 1993). Positivism refers to a realist ontological belief system (about what entities are “real”—i.e., mind-independent) and an epistemological belief that external realities can be known objectively (Morçöl, 2001). Briefly, “positivism includes the ontological belief in a deterministic universe and the epistemological beliefs that knowledge reflects external realities, the laws of the universe can be known, and science can be unified through a common methodology”—that is, one favoring deductive, inductive, and reductionist/analytical approaches and quantitative analyses (Morçöl, 2001, p. 382).

Although the approach taken in this text rejects positivism per se, it nonetheless is also consistent with Collins and Evans (2007), who take the position that science, including the social sciences, is a central element of our culture; that is, the norms and culture of evidence-based scientific argument have a central place in modern society and scientifically related expertise requires a logical space independent of politics. Social work reflects these general norms as indicated by its adoption of using research-based evidence to inform practice (see CSWE Core Competency # 2.1.6 in Appendix A). This is not to say that politics does not matter, especially in light of how government, foundations, and think tanks have come to sponsor, finance, and use research in many instances primarily for political ends (Medvetz, 2012; Oreskes & Conway, 2010; Lyons, 1969; see Appendix B), nor is to say that human behavior and the social environment are unknowable. That would be foolhardy. Acknowledging that science occupies a central place in our culture is to recognize that scientific expertise is real and substantive, and that politics and science are legitimate, even at times interrelated, domains. Further, the failure to distinguish the two analytically and substantively may all too easily lead to technological populism—in which there are no experts; to fascism in which the only political rights are those gained through supposed technical expertise; and to blunders with little wiggle room for correcting mistakes. In short, “Democracy cannot dominate every domain—that would destroy expertise—and expertise cannot dominate every domain—that would destroy democracy” (Collins & Evans, 2007, p. 18).

For our purposes, acknowledging that science occupies a central place in our culture means equipping social workers with the requisite conceptual and technical skill sets such that when they practice as policy analysts they do so (1) with the proficiency and authority of experts—that is, other things being equal, their judgments are preferred because “they know what they are talking about” (Collins & Evans, 2007, p. 11), and (2) in ways that further public participation in the policy-making process to a reasonable and feasible extent, as the circumstances under which they undertake policy analyses warrant (Hampton, 2004; Sabatier, 1988). Both objectives necessitate a “realist” approach to policy analysis, one grounded in a stratified conception of reality, knowledge, and human interests, where distinctions may be drawn between, on one hand, a realm of “intransitive” objects, processes, and events—those that must be taken to exist independently of human conceptualization—and, on the other hand, a “transitive” realm of knowledge-constitutive interests that are properly subject to critical assessment in terms of their ethical or socio-political character (Bhaskar, 1986, 1989; Norris, 1995; Sprinker, 1987). Logically contraindicative truth-claims are rejected, such as “all truth-claims are fictitious,” “all concepts [are] just subjugated metaphors,” or science is “merely the name we attach to some currently prestigious language game” (Norris, 1995, p. 121; Brown, 1998). Feminist scholar Sondra Harding (1986), who insisted that the rigor and objectivity of science are inherently androcentric and called for a de-gendered “successor science” (pp. 104, 122), nonetheless acknowledged (p. 138) that it would be difficult to appeal to feminists' own scientific research in support of alternative explanations of the natural and social world that are less false or closer to the truth while concomitantly questioning the grounds for taking scientific facts and their explanations to be reasonable (Brown, 1998, p. 534).

Postmodernists have difficulty reconciling normative positions such as “extolling the virtues of difference and condemning the vice of repressive normalization with their generally relativist theoretical positions denying any non-arbitrary basis to authority” (Calhoun, 1993, p. 96). Social workers cannot with any consistency “speak truth to power” if the ideas of truth or truth-seeking are jettisoned from our mutual understanding of what policy analysis is all about, or in the absence of a way to adjudicate competing claims about facts or the evaluative criteria used to assess the importance of values in a way that the parties involved can agree upon and abide by the outcome. Likewise, social workers cannot convincingly fault policymakers for failing to address structural factors or forces and casting policy recommendations in terms of individual responsibility for their clients' or client groups' plight if such factors are invented by or spring from the minds of analysts rather than as constituent attributes to be uncovered, discovered, or, as Reed and Alexander (2009) contend, “read” (p. 31) during the process of analysis or research. In any event, the positivist wave, such as it ever was, is long gone. Contemporary efforts such as those in political science—for example, under the rubric of a “new perestroika” and “phronetic social science”—that use positivism as a “straw” characterization to justify turning away from legitimate preoccupations with methods in the social sciences (Flyvbjerg, 2004; Schram, 2003; White, 2002) risk throwing out the baby with the bathwater. Otherwise, they may fill the bathtub with too many theoretical and methodological toys and no discernible way to assess the merits of which should be retained and which discarded to prevent overflow (Bennett, 2002; Jervis, 2002; Laitin, 2003; Landman, 2011).

Social Work and Competing in the Policy Analysis Arena

An extensive array of institutional support for the training and employment of policy analysts in academia, foundations, professional associations, and think tanks presents formidable challenges for the profession of social work to compete on anything approximating an equal footing. Appendix B provides an overview of the development of the nature and functions of this institutional support, including that of social work during its formative years and as it matured into a profession. Readers interested in the historical dimensions of how the current social and institutional environment emerged and the varying degrees of success with which issues of activism and objectivity have been handled are encouraged to read Appendix B. As has been the case historically, policy practitioners make up a small percentage of students entering and graduating from accredited social work programs, thereby limiting the overall exposure or reach of the profession. Further, by design policy practice encompasses advocacy and analysis, which need not be inherently problematic to the extent the analysis component is approached in a disinterested or objective manner—which helps to ensure the moral integrity and normative authority of the profession. As Medvetz (2012) suggests, this is no easy task in light of the contested space among such institutions as academia, historically rooted research institutes, and more recently proliferating think tanks, all of which compete for financial support, public attention, and legitimate claim as to who produces and what counts as policy knowledge.

A relative latecomer in this highly competitive process, the National Association of Social Work (NASW) launched its own think tank, the Social Work Policy Institute (SWPI), in 2009, as a division of the NASW Foundation, in order to fill gaps identified by the Social Work Reinvestment Initiative (SWRI) (http://SocialWorkReinvestment.org). SWPI seeks to secure public money in professional social work and to respond to imperatives that emerged from the 2005 Social Work Congress. Such imperatives include participation in politics and policy where decisions are being made about behavioral health and mobilization of the profession to actively engage in politics, policy, and social action. Emphasi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Acknowledgements

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Detailed Contents

- Illustration List

- Introduction

- Acknowledgements

- Acknowledgements

- Section I The World of Policy Analysis

- Chapter 1 Science, Values, and Policy Analysis

- Chapter 2 The Purpose of Policy Analysis

- Chapter 3 Approaches to Policy Analysis

- Section II Policy as Product

- Chapter 4 Evaluating Policy Proposals

- Chapter 5 Matching Policy Proposals to Problems

- Chapter 6 Costs, Benefits, and Risks

- Chapter 7 Applying Cost-Benefit Analysis

- Section III Policy as Process

- Chapter 8 Making Policy

- Chapter 9 Implementing Policy

- Section IV Policy as Performance

- Chapter 10 Approaches to Evaluation

- Chapter 11 Evaluation, Values, and Theory

- Epilogue: A Holistic Framework for Policy Analysis

- Appendix A: Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) Core Competencies

- Appendix B: Historical Overview of Policy Analysis and Policy Studies

- Web Sites

- Glossary

- References

- Index

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Policy Analysis for Social Workers by Richard K. Caputo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Pedagogía & Consejería educativa. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.