![]()

1

Concepts in Generalizability Theory

Generalizability (G) theory is a statistical theory about the dependability of behavioral measurements. Cronbach, Gleser, Nanda, & Rajaratnam (1972) sketched the notion of dependability as follows:

The score [on a test or other measure] on which the decision is to be based is only one of many scores that might serve the same purpose. The decision maker is almost never interested in the response given to the particular stimulus objects or questions, to the particular tester, at the particular moment of testing. Some, at least, of these conditions of measurement could be altered without making the score any less acceptable to the decision maker. . . . The ideal datum on which to base the decision would be something like the person’s mean score over all acceptable observations. (p. 15)

Dependability, then, refers to the accuracy of generalizing from a person’s observed score on a test or other measure (e.g., behavior observation, opinion survey) to the average score that person would have received under all the possible conditions that the test user would be equally willing to accept. Implicit in this notion of dependability is the assumption that the person’s knowledge, attitude, skill, or other measured attribute is in a steady state; that is, we assume that any differences among scores earned by an individual on different occasions of measurement are due to one or more sources of error, and not to systematic changes in the individual due to maturation or learning.

A single score obtained on one occasion on a particular form of a test with a single administrator, then, is not fully dependable; that is, it is unlikely to match that person’s average score over all acceptable occasions, test forms, and administrators. A person’s score usually would be different on other occasions, on other test forms, or with different administrators. Which are the most serious sources of inconsistency or error? Classical test theory can estimate separately only one source of error at a time (e.g., variation in scores across occasions can be assessed with test-retest reliability).

The strength of G theory is that multiple sources of error in a measurement can be estimated separately in a single analysis. Consequently, in a manner similar to the way the Spearman–Brown “prophecy formula” is used to forecast reliability as a function of test length in classical test theory, G theory enables the decision maker to determine how many occasions, test forms, and administrators are needed to obtain dependable scores. In the process, G theory provides a summary coefficient reflecting the level of dependability, a generalizability coefficient that is analogous to classical test theory’s reliability coefficient.

Moreover, G theory allows the decision maker to investigate the dependability of scores for different kinds of interpretations. One interpretation (the only kind addressed in classical test theory) concerns the relative standing of individuals: “Charlie scored higher than 95% of his peers.” But what if the decision maker wants to know Charlie’s absolute level of performance regardless of how his peers performed? G theory provides information on the dependability of scores for this kind of interpretation as well.

In this chapter, we develop the central concepts of generalizability theory, using concrete examples. In later chapters, procedures are presented for analyzing measurement data.

Generalizability and Multifaceted Measurement Error

The concept of dependability applies to either simple or complex universes to which a decision maker is willing to generalize. Our presentation will be made concrete with applications to a variety of behavioral measurements (e.g., achievement tests, behavior observations, opinion surveys) under increasingly broad definitions of the universe. We begin here with the simplest case, in which the universe is defined by one major source of variation, called a facet in G theory. Then we move to universes with two, three, or even more facets.

One-Facet Universes

From the perspective of G theory, a measurement is a sample from a universe of admissible observations, observations that a decision maker is willing to treat as interchangeable for the purposes of making a decision. (The decision may be practical, such as the selection of the highest scoring students for an accelerated program, or may be the framing of a scientific conclusion, such as the impact of an educational program on science achievement.) A one-facet universe is defined by one source of measurement error, that is, by a single facet. If the decision maker intends to generalize from one set of test items to a much larger set of test items, ITEMS is a facet of the measurement; the item universe would be defined by all admissible items. If the decision maker is willing to generalize from one test form to a much larger set of test forms, FORMS is a facet; the universe would be defined by all admissible test forms (e.g., all forms developed over the past 15 years). If the decision maker is willing to generalize from performance on one occasion to performance on a much larger set of occasions, OCCASIONS is a facet; the occasions universe would be defined by all admissible occasions (e.g., every day within a 3-month period). Error is always present when a decision maker generalizes from a measurement (a sample) to behavior in the universe.

Consider a typical school achievement test that consists of multiple-choice questions (called “items”), usually with four or five response alternatives. We consider here a simple scoring rule: right (1) or wrong (0). Based on the sample of items in the test, generalizations are made to students’ “achievement,” a generalization presumably not bound by the sample of items on the test.

If all of the items in the universe are equal in difficulty and an individual’s score is roughly the same from one item to the next, then the person’s performance on any sample of items will generalize to all items. If the difficulty of the items varies, however, a person’s score will depend on the particular sample of items on the test. Generalization from sample to universe is hazardous. Item variability, then, represents a potential source of error in generalization. Items constitute a facet of the achievement measurement. If it is the only facet being considered, the set of admissible “items” is a single-faceted universe. The decision maker, of course, must decide which items are admissible.

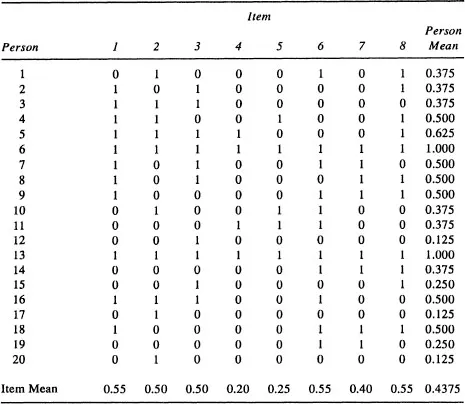

As a concrete example, consider a science achievement test for fifth graders. The test contains 40, four-alternative multiple-choice items, scored (0, 1). Table 1.1 lists scores on a random sample of eight items that call for recall of factual information, reasoning with science concepts, interpretation of data or graphs, generalization from data or experimental set-ups, or the like. We use the mean of item scores as a person’s score on this eight-item test. In practical testing, the total rather than the mean is used ordinarily. Throughout this Primer we shall use the mean of a set of observations as the summary “observed score.” This usage greatly simplifies presentation of G theory. Any result obtained for mean scores is converted easily into a statement about total scores, so nothing is lost by basing formulas on means.

Users of achievement test information—such as school administrators, parents, policymakers, or the general public—are probably indifferent to the particular questions on the science test. They would be quite willing to substitute another set of items covering similar science facts, inferences, and interpretations, or covering different instances of the same facts, and so forth; that is, the users of test information are more interested in a student’s general science achievement than the student’s score on any particular set of items. The generalized achievement is represented by the score that would have been earned on a wide variety of test items that could have been used. Because items vary in difficulty across all students or for particular students, students scoring high on one sample of items may not score high on another sample of items. Test items, a facet of the measurement, is a potential source of error in generalization.

The item facet, then, can be represented as the wide variety of items that test users want to call “science test items.” These items comprise the universe of test items. If we think of the universe, we could have a table just like Table 1.1 with two changes. First, instead of having just eight columns, we would have a very large number of columns covering all of the admissible items. (For brevity, we can use the infinity symbol ∞ for the number of items in the universe.) Second, the person mean is now the average over the whole set of items. This mean is the universe score, as contrasted with the “test score” in the last column of Table 1.1.

Ideally, test users want to know each person’s universe score. Because this ideal datum is unknown, we want to know how accurate the generalization is from the particular set of items on the science test (Table 1.1) to all admissible items as an indicator of a student’s science achievement.

A one-facet design has four sources of variability. One source of variability arises from systematic differences among students’ achievement in science. We speak of this source of variability as the object of the measurement. Variability among the objects of measurement (usually persons, in social science measurement) reflects differences in their knowledge, skills, and so on.

| TABLE 1.1 | Item Scores on Eight Items from the CTBS Science Achievement Test |

Source: The data are from New Technologies for Assessing Science Achievement by R. J . Shavelson, J. Pine, S. R. Goldman, G. P. Baxter, and M. S. Hine, 1989.

The second source of variability arises from differences in the difficulty of the test items. Some items are “easy,” some difficult, and some in between. To the extent that items vary in difficulty, generalization from the item sample to the item universe becomes less accurate.

The third source of variability arises from the educational and experiential histories that students bring to the test. For example, a test item on hamsters would be easier for a student who has raised them than for other students. The difference in ordering of students on different items constitutes, in analysis of variance terms, an interaction between persons and items. This match between a person’s history and a particular item increases variability and increases the difficulty of generalizing from a student’s score on the sample of eight science items to his or her average score over all possible items in the universe—the universe score (G theory’s analog to classical theory’s true score).

The fourth source of variability may arise out of randomness (e.g., a momentary lapse of a student’s attention), other systematic but unidentified or unknown sources of variability (for example, different students take the test on different days), or both.

In sum, four sources of variability can be identified in the achievement test scores in Table 1.1: (a) differences among objects of measurement, (b) differences in item difficulty, (c) the person-by-item match, and (d) random or unidentified events. The third and fourth sources of variability, however, cannot be disentangled. With only one observation in each cell of the table, we do not know, after accounting for the first two sources, if differences between item scores reflect the person-item combination or “interaction” (as in analysis of variance), the random/unidentified sources of variability, or both. Consequently, we lump the third and fourth sources of variability together as a residual: the person-by-item interaction (p × i) confounded with other unidentified sources we d...