![]()

PART

I

Overview of Qualitative Research Methods

![]()

1

Clinical Research

A Multimethod Typology

and Qualitative Roadmap

William L. Miller

Benjamin J. Crabtree

Welcome to the excitement, diversity, and possibilities of clinical research. Welcome to a journey of adventure. This chapter presents a roadmap of research methods to facilitate the development of a multi-method approach to this adventure, with emphasis on qualitative strategies. Five styles of inquiry are briefly identified and described. Research aims and analysis goals are then matched with these styles. The research styles are also connected to three different paradigms, and this information is all used to describe the process of choosing an appropriate style of inquiry and method for a particular research interest. This chapter elaborates a typology of qualitative methods and specific strategies of inquiry and gives overviews of how to develop appropriate qualitative research designs.

A MULTIMETHOD RESEARCH TYPOLOGY

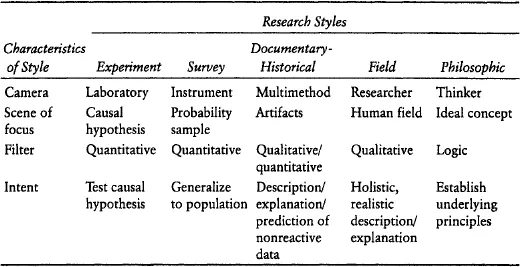

Doing research is, in many ways, like taking a descriptive and explanatory snapshot of empirical reality. For each particular photograph, the investigator must decide what kind of camera to use, what scene on which to focus, through which filter, and with what intent. At least five styles of inquiry are distinguishable, based on the primary camera, focus, filter, and intent: experimental, survey, documentary-historical, field, and philosophic (see Table 1.1).

TABLE 1.1 Characteristics of Different Research Styles

Experimental researchers create study designs that test carefully constructed causal hypotheses. The laboratory is the camera used to focus the experiment’s lens on the causal hypothesis. The laboratory, whether in a building, in the field of human activity or an ecological habitat, or in a computer simulation, is where the variable of interest is actively and measurably manipulated in tightly controlled conditions. The researcher doing the experiment wears quantitative filters that selectively gaze with accurate, measurable precision. The experimental style includes the many types of experimental designs and randomized controlled trial designs.

The survey style of inquiry, on the other hand, focuses on a representative probability sample from a defined population by means of a research instrument, such as a structured interview, observational rating scale, or questionnaire, with the intent of generalizing the resultant descriptions and/or associations to the larger population. Survey is used here in the broad sense intended by the social science traditions (Babbie, 1979; Last, 1983; Lin, 1976). The epidemiologist’s understanding of survey as cross-sectional research (Mausner & Kramer, 1985) is here understood as one example of a more encompassing survey research style. As with the experimental style, the filter and form of expression are quantitative and statistical, with emphasis on validity and reliability. Unlike the experimental style, survey research involves passive manipulation of the variable of interest. The observational designs of epidemiology, such as cohort, cross sectional, and case control, are examples of the survey style. Other survey designs include descriptive surveys; correlational, longitudinal, and comparative survey designs; time series designs; theory-testing correlational surveys; ex post facto designs; and quasiexperimental designs. Burkett (1990) and Marvel, Staehling, and Hendricks (1991) have presented useful typologies for organizing the survey and experimental styles of research.

The common denominator of the documentary-historical style is a focus on artifacts, material culture. This style is an eclectic assortment of cameras and filters. The researcher using this style gazes at an artifact through the camera and filter most appropriate for the intent. The artifacts can be archives, literature, medical records, instruments, art, clothes, or data tapes from someone else’s research. Examples of documentary-historical research include literature review, artifact analysis, chart audits, archive analysis, historical research, secondary analysis, and meta-analysis.

The field researcher is personally engaged in an interpretive focus on a natural, often human, field of activity, with the goal of generating holistic and realistic descriptions and/or explanations. The field is viewed through the experientially engaged and perceptually limited lens of the researcher using a qualitative filter. Field research is often called qualitative research. Unlike the previously discussed research styles, field research has no prepackaged research designs. Rather, specific data collection methods, sampling procedures, and interpretive strategies are used to create unique, question-specific designs that evolve throughout the research process. These qualitative or field designs take the form of either a case study or a topical study. Case studies (Hamel, Dufour, & Fortin, 1993; Merriam, 1988; Yin, 1994) examine most or all the potential aspects of a particular distinctly bounded unit or case (or series of cases). A case can be an individual, a family, a community health center, a nursing home, a habitat or neighborhood, or an organization. Topical studies investigate only one or a few selected spheres of activity within a less distinctly bounded field, such as a study of the meaning of pain for selected persons in a community.

Lastly, there is philosophic inquiry, which often serves as a generator and clarifier for the other research styles. The philosophical inquirer uses analytic skills as thinker to examine an idea or concept through the filter of logic to move toward clarity and the illumination of background conditions. Philosophic inquiry often proceeds as a thought “experiment” and is frequently based on a single case or even a hypothetical case with no empirical evidence.

Research Aims

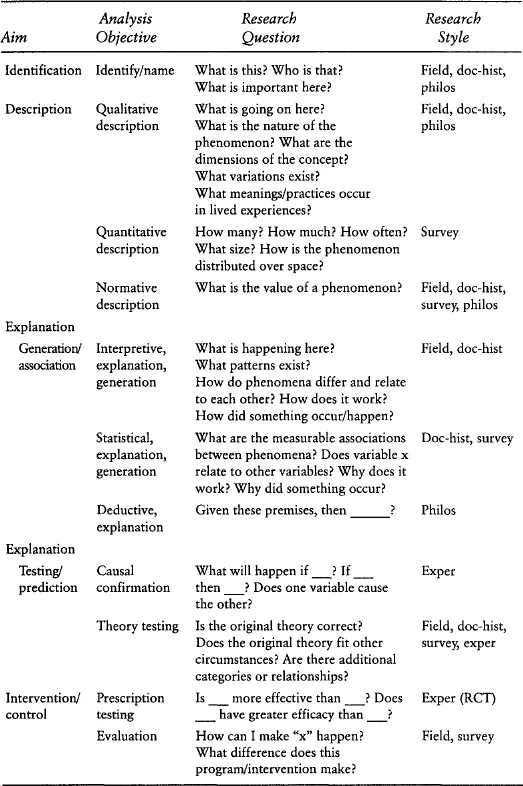

The choice of research style for a particular project depends upon the overarching aim of the research, the specific analysis goal and its associated research question, the preferred paradigm, the degree of desired research control, the level of investigator intervention, the available resources, the time frame, and aesthetics (Brewer & Hunter, 1989; Diers, 1979). There are at least five aims of scientific inquiry: identification, description, explanation-generation, explanation-testing, and control. The first three of these comprise what is often termed exploratory research. Qualitative methods are usually used for identification, description, and explanation-generation; quantitative methods are most commonly used for explanation-testing and control. These general guidelines have many exceptions, depending on the specific analysis goal (see Table 1.2).

The aim of identification is one of the most neglected aspects of scientific inquiry. All too often, investigators create concepts based on some “gut” feeling, their own reasoning, or the literature. They then produce measurement instruments that reify the concept, giving the appearance that it really exists “out there.” The result may be research that is powerful (minimal Type 2 error) and minimizes false positives (Type 1 error) but may also be solving the wrong problem (Type 3 error) or solving a problem not worth solving (Type 4 error). Qualitative field research, the documentary-historical style, and philosophic inquiry are ideally suited for the essential task of identification.

At least three types of description are distinguishable—qualitative, quantitative, and normative. Qualitative description, using qualitative methods, explores the meanings, variations, and perceptual experiences of phenomena and will often seek to capture their holistic or interconnected nature. Quantitative description, based in descriptive statistics, refers to the distribution, frequency, prevalence, incidence, and size of one or more phenomena. Normative description seeks to establish the norms and values of phenomena (O’Connor, 1990). The choice of quantitative or qualitative methods depends on how one wishes to understand and characterize the norms of interest.

Explanation-generation/association can have at least three analytic goals—interpretive explanation-generation, statistical explanation-generation, and deductive explanation. Some research seeks to discover relationships, associations, and patterns based on personal experience of the phenomena under question. This interpretive explanation-generation is best achieved using research styles with a qualitative filter such as field and documentary-historical styles. When concepts have already been identified, described, and interpretively defined, another objective is to explore possible statistical relationships using quantitatively based styles of research. Another analytic goal is to deductively generate explanations from a set of given premises. This purpose is best met using philosophic inquiry.

Explanation-testing/prediction includes both goals or intents of confirming causality and testing theory. One form of causal confirmation is to establish predictability, and another is to definitively demonstrate causality using experimental research design. Another analysis goal is to test explanatory theory by evaluating it in different contexts. The research style used to meet this intent depends on the type of explanation being tested but may often involve field strategies, especially when the theory concerns systems and/or holistic understandings.

TABLE 1.2 Research Aims, Analysis Objectives, Research Questions, and Appropriate Research Styles

NOTE: Doc-hist = documentary-historical; exper = experiment; philos = philosophical; RCT = randomized control trial.

Intervention/control is an important aim for many clinical researchers—the testing and/or evaluation of some prescription or intervention, either intentional or natural, and associated responses. One analysis goal is to test an intervention in such a way that either its efficacy or its effectiveness can be generalized to other similar situations. This is the raison d’etre for the randomized control trial (RCT). At other times, the analysis goal is to evaluate an intervention in a specific context, with no immediate expectation for generalization. Qualitative evaluation strategies are especially useful for this purpose (Chelimsky & Shadish, 1997; Patton, 1990), as well as for discovering or tracking the systemic consequences of changes or interventions. When participants are actively included in the evaluative process, field research strategies are again most helpful (Fetterman, Kaftarian, &Wandersman, 1996).

Paradigms

A paradigm represents a patterned set of assumptions concerning reality (ontology), knowledge of that reality (epistemology), and the particular ways of knowing about that reality (methodology) (Guba, 1990). These assumptions and the ways of knowing are untested givens and determine how one engages and comes to understand the world. Each investigator must decide what assumptions are acceptable and appropriate for the topic of interest and then use methods consistent with the selected paradigm. There are at least three paradigms (Habermas, 1968).

First is that knowledge that helps humans maintain physical life, our labor and technology. This is most commonly represented by positivism, the culture of biomedicine, and its associated biomedical model. Wet-lab science and quantitative methods primarily inform this knowledge, referred to here as materialistic inquiry (Figure 1.1). This paradigm can he metaphorically understood as “Jacob’s Ladder.” The materialist inquirer values progress, stresses the primacy of method, seeks an ultimate truth—a natural law—of reality, and is grounded in Western, monotheistic tradition. Materialistic inquiry is best for social engineering and its need for control and predictability. It emphasizes rationality and, within the realm of health care, strives toward the elimination of disease and the achievement of immortality (Schwartz, 1998). If one wants to understand the molecular genetics of hyperlipidemia or to develop a new drug, then this is the paradigm of choice. The materialist inquirer climbs a linear ladder to an ultimate objective truth. Most researchers using materialistic inquiry now refer to their use of a postpositivist paradigm that has expanded to accept multiple constructed realities and the impact of the observer on that which is observed. The postpositivist perspective seeks successive approximations to reality but understands the unlikelihood of getting to ultimate reality.

Figure 1.1. Diagram of Materialistic Inquiry

A second paradigm is based on that knowledge that helps humans maintain cultural life, symbolic communication, and meaning, and it is referred to here as constructivist inquiry. This paradigm has also been called “naturalistic inquiry” (Kuzel, 1986) and “interpretivist thinking” or interpretive inquiry (Gadamer, 1976; Guba & Lincoln, 1989). We acknowledge that the choice of constructivist glosses over some intense debates. “Con-structivists” claim that truth is the result of perspective; it is relative. There is no objective knowledge (Gergen, 1986; Goodman, 1984). “Interpretivists” trace their roots back to phenomenology (Schutz, 1967) and hermeneutics (Heidegger, 1927/1962). This tradition also recognizes the importance of the subjective human creation of meaning but doesn’t reject outright some notion of objectivity. Pluralism, not relativism, is stressed, with focus on the circular dynamic tension of subject and object (Denzin, 1989b; Geertz, 1983). Although we take the more pluralistic approach, constructivist inquiry is the term selected because it is human constructions being studied and because it is constructions that the researcher is cocreating with the texts. This paradigm overtly acknowledges and builds upon the premise of the social construction of reality (Berger & Luckmann, 1967; Searle, 1995). We also believe the use of the word interpretive may be confusing, as it also refers to the methods-related task of analysis in field research. We believe it is important to keep paradigm choice and method choices separate. Qualitative methods generally inform constructivist knowledge (Figure 1.2), which can be depicted by the metaphor of “Shiv...