The Linkage of Domestic and Foreign Policies

With America’s economy sputtering, interest rates near zero, and the threat of a second recession looming, America’s Federal Reserve announced a third round of “quantitative easing” (QE3) in September 2012. The Fed would purchase up to $40 billion a month of U.S. mortgage-backed bonds to increase America’s money supply and provide financial institutions with additional capital that could be loaned to businesses and individuals who would spend the funds, thereby stimulating the domestic economy and reducing unemployment. The action, advocated by Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, had domestic objectives but, owing to globalization, would have a powerful impact abroad. Foreign critics, notably in Brazil, China, and Russia, contended that the Fed’s action would weaken the U.S. dollar, raise the value of their currencies, and harm their ability to export, while triggering volatile investment flows from America to the developing world. Brazil’s finance minister described QE3 as “selfish” and expressed fear about a currency war of competitive devaluations. Bernanke responded that the Fed’s policy would hasten America’s economic recovery, thereby aiding the global economy because Americans would be able to buy more foreign goods. As the Fed’s decision illustrates, the domestic and foreign arenas are no longer isolated from each other.

Recent decades have witnessed growing links between the domestic and foreign arenas. President Barack Obama came to office in 2008 promising a foreign policy based on domestic values. America’s domestic policies were profoundly affected by wars in Korea and Vietnam and, more recently, by wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. International organizations and agreements such as the World Trade Organization and the North American Free Trade Agreement have a direct impact on America’s domestic economy. Conversely, domestic policies on trade, taxation, economic investment, and even civil rights have a significant impact overseas. Frequently issues that arise in a domestic context have major consequences overseas. Thus, the appearance of a 14-minute U.S. film trailer posted in July 2012 on YouTube, featuring a blasphemous treatment of the Prophet Muhammad, produced rage throughout the Islamic world after it appeared on Egyptian television.

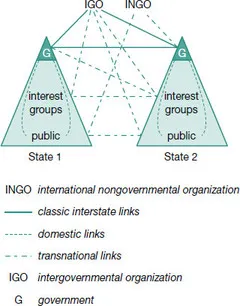

All countries are subject to external influences, and their external environment is in turn affected by domestic events. Foreign policy is the point at which influences arising in the global system cross into the domestic arena and domestic politics is transformed into external behavior. The traditional state-centric view was that America, like other states, is sovereign and, as such, controls its boundaries and territory, is subject to no higher external authority, and is the legal equal of other states. This perspective assumes that sovereign states have a clear and unitary national interest, and that their governments interact directly with one another and with international organizations. It also assumes that publics and domestic interest groups in different societies do not interact directly with those in other societies. Instead, they present their views to their own governments, which then represent them in relations with other governments. Figure 1.1 illustrates this perspective in which interstate politics remains distinct from domestic politics.

The traditional model is inadequate to describe the full range of factors shaping foreign policy. In the words of former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, “increasing global interconnectedness now necessitates reaching beyond governments to citizens directly and broadening the U.S. foreign policy portfolio to include issues once confined to the domestic sphere, such as economic and environmental regulation, drugs and disease, organized crime, and world hunger. As those issues spill across borders, the domestic agencies addressing them must now do more of their work overseas, operating out of embassies and consulates.” 1

Figure 1.2 presents a picture of a transnational world in which external and domestic factors interact directly. The domestic pyramid of policy formation is penetrated at several levels, and links among governments and domestic groups are multiplied to reflect the complex exchanges that occur. Thus, there is interaction among interest groups at home and abroad and governments, among interest groups in different states, and among interest groups and both international and nongovernmental organizations.

Figure 1.1 Model of State-Centric World

Source: Adapted from Robert O. Keohane and Joseph S. Nye, Jr., “Transnational Relations and World Politics: An Introduction,” International Organization, Summer 1971: 332–334.

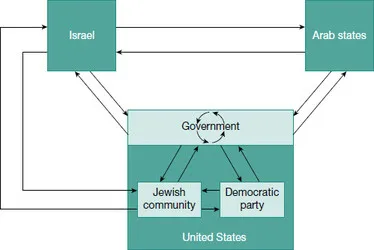

The complexity of relations between societies and states at home and abroad was reflected by American recognition of Israel. Israel declared its statehood in 1948, a presidential election year in America. Both candidates had to take a position about whether to recognize Israel, but it was especially important that Harry Truman, the incumbent Democrat, adopt a favorable attitude toward the new state because he sought Jewish political and financial support in key states like New York. For Truman, Israelis constituted a significant constituency because of their links with America’s Jewish community. Truman adopted a pro-Israeli policy, despite objections from the Departments of Defense and State, which feared that recognizing Israel would alienate oil-rich Arab states. Figure 1.3 represents schematically the links among groups in 1948 that interacted in relation to the question of recognizing Israel. Arrows represent the flow of communications among key actors. To understand Truman’s decision, we would have to describe communications between him and other government officials, between the government and groups like the Jewish community and the Democratic Party, and between the U.S. government and those of other countries.

A similar link between the domestic and external arenas involving the Middle East was evident during the 2012 U.S. presidential election. President Obama and Republican candidate Mitt Romney in a televised debate on October 16, 2012, vigorously disputed the assault on the U.S. consulate in Benghazi, Libya, that climaxed with the death of America’s ambassador. Earlier in the campaign, Governor Romney had visited Israel, where he depicted Obama as hostile to Israel and weak toward Iran. Injecting himself in the campaign, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu gave a speech at the United Nations in which he declared that Iran was approaching the point where it could produce a nuclear weapon and urged Washington to act before it was too late. As this case suggests, affiliations and identities that cut across national boundaries are important factors in foreign policy. Thus, analyzing only diplomatic relations among governments is insufficient to explain foreign policy, and studying foreign policy entails awareness that traditional boundaries between “foreign” and “domestic” policies have eroded.

Figure 1.2 Model of Transnational World

Source: Adapted from Robert O. Keohane and Joseph S. Nye, Jr., “Transnational Relations and World Politics: An Introduction,” International Organization, Summer 1971: 332–334.

Moreover, globalization has facilitated the movement of persons, things, and ideas across national boundaries, making them increasingly porous. Even a superpower like America is “penetrated” by flows of illegal migrants, illegal drugs, and subversive ideas. For its part, Washington employs a variety of tools to penetrate foreign societies—propaganda favoring democracy and human rights in countries like China and Russia, covert assistance to opposition groups in hostile states like Iran, foreign aid to friendly governments, and financial and political support for American corporations like Boeing.

Figure 1.3 Communication Model Israeli Recognition Process, 1948

Source: Raymond F. Hopkins and Richard W. Mansbach, Structure and Process in International Politics (New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1973), 135.

Sources of Foreign-Policy Influence

Let us now examine the major sources of influence on U.S. foreign policy. We shall discuss five categories of factors that influence American policymaking: external factors, government factors, role factors, societal factors, and individual factors. 2 The degree to which these affect foreign policy varies by country. For example, the United States is a large democracy with a high level of economic development. As such, it has a large government with numerous foreign-policy agencies and bureaucracies as well as innumerable societal pressure groups. And, increasingly, interest groups at home and abroad are linked transnationally. External factors, while important in shaping U.S. policies, are likely to have a greater impact on small countries like Denmark or Singapore because they are more dependent on trade and allies for economic and military security, while societal factors are likely to have less of an impact in countries like Russia and China that have authoritarian governments that limit the freedom of social groups, unlike the United States, which is an open society, governed by democratic norms and the rule of law. In addition, in large countries like America, the impact of particular individuals like the president, while substantial, is likely to be constrained by the many bureaucratic and social actors competing to have their views taken account of.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu warns the United Nations about Iranian weapons of mass destruction (WMD).

AP Photo/Seth Wenig

External Factors

Globalization itself is perhaps the leading external constraint on foreign policy because interdependence dilutes American sovereignty, makes the United States increasingly vulnerable to the actions of other countries and, as the opening paragraphs of this chapter reflect, makes those countries more vulnerable to U.S. policies. Globalization also is a key source for the disappearing distinction between domestic and foreign policy. President Obama explicitly recognized growing global interdependence when, on entering office, he spoke of the need for multilateral cooperation and “common problems.” Thus, globalization and the interdependence of the U.S. economy with economies worldwide were largely responsible for the rapid spread worldwide of America’s subprime mortgage crisis in 2007 to 2008, and Obama declared that restoring U.S. influence abroad required reinvigorating the economy at home. In a word, America’s recession became a global contagion.

The porosity of U.S. borders makes it vulnerable to flows of people, things, and ideas from abroad, for instance, cyberattacks, extremist political views, drugs, diseases, terrorists, and any interruption in patterns of trade. One such interruption was triggered by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan and the subsequent nuclear crisis that interrupted global supply chains in a variety of transnational industries including the production of and trade in automobiles and consumer electronics.

Other external factors of great significance are the distributions of resources and attitudes in the global system. America’s own resources—economic, military, political, and social—are part of the country’s domestic environment, but the distribution of such factors elsewhere is external and must be considered by decision makers in Washington. American decision makers must ask what U.S. capabilities are relative to those of potential friends and foes rather than what is the absolute level of American capabilities. Thus, American military and economic capabilities have declined since the end of the Cold War in relative though not in absolute terms.

Although some observers conclude that America is losing the military and economic dominance it enjoyed after the Cold War, 3 this does not mean that America is in the midst of absolute decline. China, for example, is “rising” but remains behind the United States on most dimensions. As political scientist Joseph Nye observes: “The word ‘decline’ mixes up two different dimensions: absolute decl...