![]()

STRATEGIES

FOR INTERPRETING

QUALITATIVE DATA

MARTHA S. FELDMAN

University of Michigan

1. INTRODUCTION

As I sit in my office up to my eyeballs in data, I am once again impressed with the enormity of the problem of analyzing qualitative data. I have audiotapes, floppy disks, and written documents. I have my field notes and some of my students’ field notes. I have copies of reports and minutes of meetings. I have between 10,000 and 20,000 electronic mail messages and another 2,000-3,000 pieces of hard copy mail. I have buttons and calendars and thank you notes. It will take me several weeks working full time just to review all these materials. How am I to make sense of them?

Many people who have worked with ethnographic or other qualitative data will recognize these feelings. The task can be overwhelming. One sometimes feels that reviewing the data only reinforces the complexity and ambiguity of the setting. While it is well to remember this complexity and ambiguity, the task at hand is to create an interpretation of the setting or some feature of it to allow people who have not directly observed the phenomena to have a deeper understanding of them.

Interpretation Creation

The tricky part of this interpretation creation, of course, is to create an interpretation that is neither simply the application of some preexisting theory to your data nor only a description of how the members of a culture understand particular phenomena. Either of these is possible, but often one wants to go beyond these. By the time you have completed fieldwork, you have so much data that, if you were looking to support a particular theory, you probably could. That is not, however, the point of this research. If that is the intended goal, there are much more efficient ways to achieve it. At the same time, the goal is not only to describe a culture. Though describing a culture (or even knowing it well enough to start to describe it) is very difficult and, of course, one cannot describe a culture without also interpreting it (Clifford, 1986), people who do qualitative research are often expected to go quite a bit beyond describing what members know about the culture. The goal, it seems to me, is to develop one’s own interpretation of how parts of the culture fit together or influence or relate to one another that is intrinsic to the setting one has studied and, at the same time, sheds light on how similar processes may be occurring in other settings.

If we accept this end, the present problem is how to start. Starting to create an interpretation is like trying to start a jigsaw puzzle that has a million indeterminate pieces. To make this puzzle more confusing, there is no unique solution. That is, one piece may fit with many other pieces. Imagine, in addition, that the picture consists almost entirely of shades of gray (imagine a jigsaw puzzle of a Rothko painting) so that one does not get immediate clues about the fit of the pieces from the picture that forms. (If one were to take this puzzle metaphor too literally, one might think that I am suggesting that there is ultimately a right answer. I am not. While I do not think that all interpretations are equally reasonable or legitimate, I also understand that these concepts—reason and legitimacy—are culturally bounded.)

My experience with ethnographie data suggests that clusters of data tend to stick together. These clusters probably depend on both what is in the researcher’s thoughts as the data are gathered and how the members of the culture tend to organize their culture. Some of the challenges at this point of the research involve how to loosen the boundaries of these clusters, how to encourage clusters to interact with one another, and how to access clusters that have potential for interacting. The techniques for data analysis that I describe in this book all have the potential to help the researcher with these challenges.

Purpose of This Book

My purpose in writing this book is to introduce and give examples of some interpretive techniques for analyzing qualitative data. In choosing the four theories that underlie these techniques, I have focused on theories that are oriented to the interpretation of cultures or the context in which actions are taken. In every case I have seen the techniques used, I have been impressed with how much information they allow the author to provide the reader in a relatively succinct manner. I have used each of the techniques with my own data and have been struck by how much more I understand and can communicate about a culture or context after using the techniques. I also like the theories from which these techniques are drawn because they each have relatively few assumptions so that they are applicable to a broad range of phenomena. I do not claim that they are the only useful theories or techniques. Others may be equally or more useful for certain pieces of research. I also recognize that each of the theories I present could be used independently and that each warrants a book of its own. In fact, each has many books devoted solely to it, and I cite many of these books in the text. I find, however, that it is also useful to analyze data from the combined perspective of these theories. As I discuss in Chapter 6, while each of the theories focuses on different aspects of a context, when all four perspectives are combined, the aspects are interrelated in a way that makes the result a rich and textured interpretation of the context. Of course, by focusing on only one of the theories, one can go more deeply into a particular aspect of the context. Individual researchers have to make their decisions about which is more appropriate for their research. In this text, I try to provide the reader with a basic understanding of each of the four theories and some of the techniques for analyzing data that derive from these theories. I provide references so that the reader may pursue in greater depth any of the four theories. I also illustrate the techniques with examples from my own data.

Four Theories

The techniques of analysis I describe are based on ethnomethodology, semiotics, dramaturgy, and deconstruction. All of these theories have assumptions and the researcher must be careful that the assumptions are appropriate to the setting being studied. To my mind, these assumptions are relatively minimal. It is, however, entirely possible that the assumptions do not hold in all contexts. It is therefore important to be aware of them. In this introduction, I briefly describe the main ideas important to each of the techniques. A thorough understanding of the techniques and their appropriate uses is probably best developed through experience. In the following, I attempt to provide a basic understanding by addressing the question of what one is likely to look for and find if one looks through the eyes of an ethnomethodologist, a semiotician, a dramaturgist, or a deconstructionist.

Ethnomethodologists look for processes by which people make sense of their interactions and the institutions through which they live. They assume that people do make sense of these phenomena and that their sense making is the basis of their future actions and interpretations (what ethnomethodologists refer to as “going on”). They look for instances in which people have trouble “going on” or for ways in which the “going on” could be problematic but isn’t. In other words, ethnomethodologists look for two apparently diametrically opposed situations: breakdowns and situations in which norms are so thoroughly internalized that breakdowns are nearly impossible. Because ethnomethodologists believe that breakdowns are fairly rare, the focus tends to be on widely accepted and taken-for-granted practices. These practices are often characterized by agreement about what is appropriate and tautological explanations of their appropriateness. (For instance, if asked why an action is appropriate, a person might respond that it is the right thing to do.)1

A semiotician looks for surface manifestations and the underlying structure that gives meaning to these manifestations. Denotative and connotative meanings are linguistic terms that are often used in semiotics in relation to surface manifestations and underlying structures. Denotations are explicit meanings and connotations are implied meanings. For example, the denotative meaning of the word door is a “hinged, sliding or revolving barrier that closes an entrance or exit” (Oxford American Dictionary, 1980). Its connotation depends on the context. It might connote hidden possibilities, possible linkages, closure, and so forth. Because not all semiotic analyses are of language, the term surface manifestation is often substituted for denotation. Rather than the word door, we may be talking about an actual door. Either the word or the physical manifestation may have connotations or implied meanings depending on the context. An underlying structure is a reasonably coherent set of connotations. The same underlying structure gives meaning to many different denotations or surface manifestations.

A person carrying out a dramaturgical analysis is looking for a performance. Standard dramaturgical categories include scene, acts, actors, means, and motives. The primary focus of a dramaturgical analysis is the meaning of a performance for the actors and the audience or potential audience. A dramaturgical analysis has much in common with semiotics. Features of the performance could be considered surface manifestations and the meaning of the performance would be the underlying structure. The dramaturgical approach, however, constrains the focus of analysis to events and draws attention to particular features of an event. Dramaturgical analysis tends to focus on people in their roles and on the intentional strategies they have for producing desired understandings or effects.

A deconstructionist looks for the multiple meanings implicit in a text, conversation, or event. A deconstruction points out both the dominant ideology in the text, conversation, or event and some of the alternative frames that could be used to interpret the text, conversation, or event. Taken-for-granted categories (often in the form of dichotomies) and silences or gaps are elements that support the dominant ideology. Disruptions (sometimes in the form of a slip of the tongue or a joke) are elements that reveal the possibility of other meanings and the instability of the dominant ideology.

In the following chapters, I discuss each of these theories in turn. My objective in these discussions is to provide the readers with sufficient information to be able to use the techniques with their own data. I assume that the techniques will be used after the researcher has in-depth knowledge of the events being studied and the context in which they take place.2 This knowledge may have been gained through participant-observation or interviews or other data gathering techniques.3 I also assume that the researcher has data in the form of field notes, interview notes, audio- or visual tapes, hard copy documents, or other forms as appropriate to the setting. I do not specifically talk about ways of managing these data. I assume that the data are used as a record of events and context and also to remind the researcher of aspects of the events or context that she or he has forgotten and to fill in features of the events or context that she or he did not notice at the time of data collection. In this sense, I treat the knowledge of the researcher and the data as coterminous. From this point on, when I use the term data I am referring not only to notes or tapes or other tangible objects but also to what the researcher knows as a result of the data gathering process. The analysis I describe, then, is not simply a matter of combining and recombining the recorded or collected data. It also involves using one’s knowledge of the setting to determine which of the data are relevant, to have reasons for combining different pieces of data, and, at times, to fill in information that is not in the recorded data. This latter use of one’s knowledge is particularly relevant for observational data. Because the recorded data are one’s observations and not all observations are recorded at the time field notes are taken, one may find that something one saw but failed to record is a relevant and necessary piece of information.

Background Information

The data I use for the examples are from a four-year case study in the campus Housing Department of a major U.S. state university. The purpose of gathering these data was to understand more about change in organizational routines. By organizational routines, I mean repeated organizational actions carried out by two or more interdependent actors. Hiring processes and budgeting processes are examples of such organizational actions. While much of what people do while performing these organizational routines is repeated from previous times, the actors are also often quite sensitive to the context in which they are performing. As the context changes, so may aspects of the routines. Further theoretical background on organizational routines is not included here because the focus is on the techniques of analysis. In this text, I wish to demonstrate how the techniques of analysis can be used to create an interpretation of a setting. The interpretation, then, provides a basis for understanding issues within the setting. For me, for instance, the interpretations provide a base for understanding more about change in organizational routines. I do not talk about my understandings of change in organizational routines in this text. These will appear in a later work (Feldman, forthcoming). The focus here is on understanding the setting in which the routines take place.

The reader does need to know some information about the campus Housing Department to be able to understand the examples. In the following, I provide some basic information. Throughout the text, I give more information as necessary for specific examples.

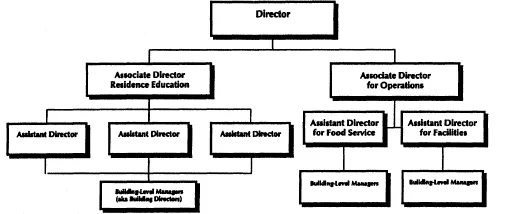

Figure 1.1. Campus Housing Department (partial organizational chart)

In this text, and indeed in everything I write about this department, I focus on specific aspects and necessarily omit others. While I cannot enumerate here the many functions the department serves, I can say that the employees of the department provide a service essential to the university community and that my long period of involvement with the department led me to respect and admire much of the work and most of the people.

The campus Housing Department provides housing for about 10,000 single students and about 1,700 married students and their families. My focus is on the part of the organization that deals with single-student housing. These students reside in approximately 15 buildings or complexes. Each building has three coequal managers. There is one manager in charge of food service, one in charge of maintenance and housekeeping (facilities), and one in charge of Residence Education. (See Figure 1.1.)

Residence education is the major focus of my study. Residence Education consists of an associate director, three assistant directors, and 16 people who report to the assistant directors. Most of these 16 people are the building level managers in charge of Residence Education. They are called building directors, and they manage a staff of from 3 to 40 students (depending on the size of the building) who live in the buildings. These students are called resident directors and resident advisors.

The routines I observed in this organization were the reserves process (a budgeting routine in which approximately 10% of the annual budget is spent), the opening and closing of buildings, and the staff selection process (the process of hiring the approximately 300 resident staff who work for the building directors). I describe these routines in more detail throughout the text as necessary for understanding the use of the analytical techniques.

NOTES

1. In my research with Lance Bennett on jury trials, for instance, we asked people to assess the credibility of stories. There was widespread agreement on which stories were credible. When we asked why a story was credible, people said things like “because it sounded right” or “because it was believable.” The task for us as ethnomethodologists, then, was to find out what made a story “sound right.”

2. See Agar (1980) and Lofland and Lofland (1984) for excellent discussions of the entire research process for qualitative research.

3. See Agar (1980), Lofland and Lofland (1984), and Spradley (1979) for discussions ...