eBook - ePub

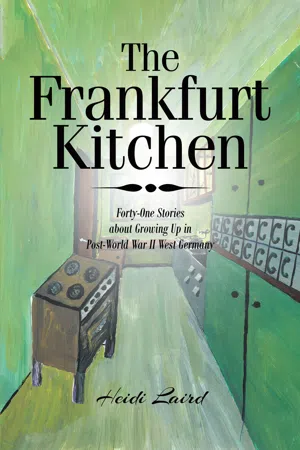

The Frankfurt Kitchen

Forty-One Stories of Growing Up in Post World War II West Germany

- 306 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The author grew up in Germany during the postwar era, when the United States evolved from a military occupation force to a peacetime cultural power, wielding vast influence in the world through its example as a country aspiring to great ideals, like freedom, equality, inclusion, acceptance of diversity, and generosity. This book tells

the personal story of how the image of America shaped the author's youthful ideas about the world she wanted to live in, as she struggled to make sense of her complicated heritage as the daughter of a Jewish father and a Christian mother, andas an adolescent inheriting the aftermath of the Nazi reign of terror.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Frankfurt Kitchen by Heidi Laird in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Deutsche Geschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Acknowledgements

Over the years, as I told stories from my childhood to entertain family and friends during long car rides, around campfires, and at all kinds of social gatherings, I often heard: “You have got to write this down!” Finally I did. It took much longer than I ever thought it would, it left me alternately exhilarated and exhausted, and it showed me, as if I didn’t already know, how sharply childhood experiences sculpt our character, and how deeply they carve themselves into our souls.

I want all who urged me to write this book to know that I would not have written it without their encouragement and enthusiasm for the project. On the technical front, I learned how to put together a proper book from my loyal and patient publication guide, Shannon Kuno.

On the home front, my husband Ted Knipe provided just the right mix of good advice, objective observations, and enduring emotional support for this sometimes harrowing venture into the realm of remembering.

My thanks to all!

1

The Jeep Driver

If I wanted to make a movie of my life, the first scene would show my mother, youthful and resolute, with soft hands and vestiges of former elegance, and me, almost eight years old and unafraid, standing in the driving rain of a cold April downpour by the side of the on-ramp to the Autobahn between Heidelberg and Frankfurt, hitchhiking. For a population of war survivors challenged daily by the extreme scarcity of basic resources, hitchhiking had become as normal as standing on a platform, waiting for an unreliable train. Eventually it would come, and you could get on.

It was 1949, and my mother, Vera Schaefer, was on one of her trips to visit my father, Harry Saarbach, in Frankfurt, about an hour’s drive from Heidelberg. I was with her, as usual, because she took me along wherever she went, maybe because I was her oldest child or because I was her only daughter, an easy and familiar companion. We were drenched, teeth chattering, chilled to the bone, but Vera said that there was an advantage to our dire situation because in this weather, we had no competition from other hitchhikers on this on-ramp, of whom there would have been many on a sunny day. Of course we were extremely grateful when a U.S. Army Jeep stopped for us, and a lean, fit man in an American military uniform came running from behind his vehicle under a dripping tarp, pulled us under the tarp with him, and opened the passenger door, behind which a person was trying to get out of the way so that the back of the seat could be folded forward and we could climb into the rear of the jeep.

When the jeep was moving again, I noticed that the person who had settled back into the front passenger seat was a very pretty young German woman, who smiled at me with an air of beguiling benevolence and then turned to Vera to ask where we were going. She said that she and her boyfriend were also going to Frankfurt and that they would be happy to drop us off at the location where Harry worked. Vera and the soldier’s girlfriend continued their conversation across the back of the passenger seat, in German, with occasional questions and comments—in English—by the kind and generous American who had treated us with so much personal warmth and concern for our safety.

I observed this resourceful man with his crew cut and weathered face as he navigated his jeep through the driving rain, peering through the small upside-down cone on his windshield, which the screeching and whimpering windshield wipers managed to keep clear, while he clutched the handle of the vibrating gearshift with his right hand, calming and reassuring the engine as it bucked and bolted through the deluge. I noticed that he was doing all this while apologizing for the leaks in the jeep’s canvas roof and sides, through which heavy drops and rivulets freely entered the interior of this brave little warrior machine. Trying to sort out this adventure in my mind, I sensed that the soldier had spontaneously acted in good faith on his impulse to get a woman and her child out of a punishing rainstorm, disregarding the fact that, as a member of the military force occupying the country of a former enemy, he had broken the unwritten but well-understood rule that transporting unauthorized German civilians in U.S. military vehicles was prohibited.

In the course of this trip, I came to see the jeep driver with my almost eight-year-old eyes as an emissary from the America, which had led the Allies to victory over the Nazi terror. These Americans were generous, well-meaning people who were bringing peace, feeding starving populations, freeing prisoners, and liberating countries from dictatorships. This early adventure of riding in the American jeep set the idealizing tone for my numerous experiences with Americans, which would follow our eventual move to Frankfurt.

What had probably nurtured my early perception of the Americans as a generous people was the ongoing drama of the Berlin Airlift, described daily on the radio and in the movie theaters’ newsreels, and followed with wonder and disbelief by the German population, including my parents. At the time of my memorable jeep ride, the Berlin Airlift was approaching the end of its improbable ten-month mission to supply the 2.2 million trapped people of West Berlin with absolutely everything they needed to survive the Soviet blockade imposed on them in June 1948. For 322 days, the newspapers and radio broadcasts chronicled the unimaginable feat of one airplane after another landing in Berlin every sixty to ninety seconds, day and night, delivering all the food, medications, dry goods, hardware for machinery repair, shoes and clothing, firewood, and coal, which the besieged population needed during the long blockade. In all, the Berlin Airlift had transported almost two million tons of provisions to the people in the encircled city by the time the blockade was lifted on May 12, 1949. After its successful conclusion, the Airlift quickly became a fabled event and joined the story of the Invasion of Normandy in the record of the defining moments of twentieth-century history. To honor the memory of the seventy-nine people who lost their lives in Airlift-related accidents, a monument greeted travelers for many years as they passed through the Berlin Tempelhof Airport before it ceased operations.

A smaller version of the Airlift was the CARE program, founded in 1945 to provide relief to survivors of World War II. CARE sent hundreds of thousands of packages to individual families, including mine, during the famine years after the war. These cardboard boxes, approximately 20" × 16" × 18", filled with survival foods like canned meats, evaporated milk, shortening, flour, powdered eggs, and deeply appreciated surprise gifts such as a bar of fragrant soap or a chocolate bar, items which, in the midst of famine, were received with a feeling of reverence, soon followed by fear that this treasure could be stolen if not quickly hidden away in a safe place. One of our CARE packages was, in fact, plundered by a thief who had climbed through a first-floor open kitchen window in broad daylight. I still hear Vera’s angry cries when she discovered the theft.

A vehement discussion that a curious child could have overheard in the years after the war was about the Marshall Plan, America’s iconic program to restart the ruined economies of Western Europe, including that of the hated and now destroyed Germany. The Marshall Plan was at first rejected by people in Congress who wanted to see Germany plowed under and turned into an agrarian society, which would never again start a war. This was the vision of the secretary of the treasury, Henry Morgenthau. Advocates of the Marshall Plan countered that rebuilding the German industry and helping the Germans create a new version of their first, unsuccessful attempt at democracy would enable them to build a strong economy and produce a rich return on the U.S. investment. The goal of this gigantic project was to make the war zones livable again by removing the mountains of rubble and debris in the cities, finding and defusing the thousands of undetonated bombs and live ammunition that lay beneath the ruins and putting people to work under the direction of the U.S. military government. This initial cleanup would create the environment in which the dead German economy could come back to life and form the basis for future prosperity, security, and political stability in Western Europe. It was argued that in addition to the massive return on the U.S. investment, a grateful former enemy would become an important trade partner and loyal ally in the shifting power dynamics of the emerging Cold War.

As Germany, Italy, France, and England rebuilt their economies, they could afford to start buying America’s products and, along with buying its products, imported its culture. As it turned out, the Marshall Plan succeeded beyond anyone’s expectations. The success of the Marshall Plan led to the unquestioned acceptance of American political and cultural leadership and moral authority in the postwar world. While I was obviously too young to participate in the conversations going on around me in my childhood, the changes I saw in my immediate environment, from ruined cityscapes to new construction everywhere, from famine and empty store shelves to a reliable food supply, shaped my perceptions and gave me guidelines for forming opinions about what was normal and what was not.

What I later read in history books was that, one month after the jeep ride, on May 23, 1949, in a giant step away from the World War II catastrophe and into an uncertain future, Germany’s first postwar government was officially recognized by the U.S., France, and England, who withdrew their military governments from the three zones into which they had divided western Germany at the end of the war. The Soviet Union had opposed the formation of an autonomous West Germany, and Stalin denounced this move. If I don’t remember any discussion at home about the momentous ceremony of swearing in the first chancellor of West Germany, Konrad Adenauer, it is probably because its significance remained abstract and nebulous to me and possibly also because it caused little debate in the general population, which was preoccupied by its struggles with extreme housing shortages, scarce resources, and an infrastructure still largely in ruins.

Also happening without much fanfare was the movement in the Western European countries, the new West Germany among them, to appoint the United States as the universal peacekeeper and, still traumatized by the war, to work toward a European Union, in which any future war would be unthinkable. The United States was entrusted with the power to organize the defense of Europe with the establishment of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in 1949. The treaty included the provision that if one of its members were to be attacked, all the other parties to the treaty would come to that member’s defense.

As it turned out, the only time that a NATO member was attacked was on September 11, 2001, and the NATO allies promptly stepped forward and joined the United States in its war in Afghanistan.

How all those historic events fit together was obviously something that I only understood years later, but it was easy for a child at that time to absorb a sense of alarm and pessimism amid the building boom and feverish business activity, usually from overhearing adult conversations about the atom bomb, guided missiles, Soviet aggression, and the Cold War. Making that point more directly were comments such as the one made by Harry when Vera complained to him about some punishable mischief by my younger brothers, Stefan and René: “Let the boys have their fun. They won’t have a future anyway when the Russians come.”

I am sure that I did not reflect much on geopolitics as I grew up in postwar Frankfurt, where the American military continued to have high visibility, from the U.S. military personnel and their camouflaged vehicles on the streets to the large station wagons from Detroit, the PX shopping centers, the Armed Forces Network radio stations, the Stars and Stripes newspaper, and the American playhouse, where amateur actors, recruited from military families performed plays by Arthur Miller and Thornton Wilder’s Our Town. And there was—unbelievably—the Seventh Army Symphony Orchestra, consisting of young American musicians who were serving their obligatory two years in the military as goodwill ambassadors in the country of their former enemies. These musicians now found themselves in the land where much of their classical repertoire had been composed, and I have often wondered how they balanced their roles as soldiers occupying the country whose culture produced so much of the music they surely loved.

What I came to sense rather early in my years of growing up in the land of the United States Seventh Army was that America meant so much more than military dominance. America meant free elections and the rule of law, scientific research and technology, popular culture, and ethnic diversity; it meant support for freedom of speech and artistic expression, it meant all the ideas which would later be called the liberal world order, and it meant being the first responders in global crises. This is what built America’s enormous soft power and made the United States a spectacular country in the eyes of people all over the world, who had known only kings and tyrants.

This exposure to American life and the social and cultural climate of the time inevitably shaped my thinking and influenced the plans I made for my life. It also nurtured my belief that the democratic values that the United States represented were taking a firm hold all over the world and would in the future only become stronger. I believed predictions that more and more countries would be governed by the rule of law, and the rule of executive order by dictators was becoming a thing of the past.

As I write this seventy years later, in the year 2019, I recognize how distant this idealized vision of America has become, and I wonder if it will be possible to say seventy years from now that the principles and values of America’s founders have survived.

2

Sebastopol

Vera’s bold initiative as a hitchhiker on an Autobahn on-ramp was a small feat when compared to other arduous journeys that she had taken in the previous ten years of her life. She had met Harry, a Jew, in 1937, at a time when it was no longer possible to pretend not to be frightened by the growing Nazi hate campaigns and systematic aggression against Jews, and they fled together to Paris, expecting that this move would keep Harry safe.

When Hitler invaded France and Paris fell in June 1940, the quickly installed Vichy regime eagerly collaborated with the occupying Nazi forces and immediately detained all foreign nationals in internment camps. Vera was separated from Harry and found herself within days on a detainee transport back to Germany, where her father, Karl Schaefer, agreed to let her live in his large house in Mannheim, which she had sworn she would never set foot in again after her last angry confrontation with him. Harry, when urged many years later to tell the story of how he made his way back to Germany, said that he had found a way to escape from the internment camp by impersonating a German military driver summoned to fill in for a regular army driver who had not shown up as scheduled. Harry was assigned a truck and given the necessary travel documents to pass through all the Nazi checkpoints up to the German border, where he abandoned the truck and “went underground.”

Harry never talked about his “underground” years, but members of Vera’s family still tell stories about the times when he would unexpectedly show up for short visits before disappearing again, usu...

Table of contents

- Acknowledgements