- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

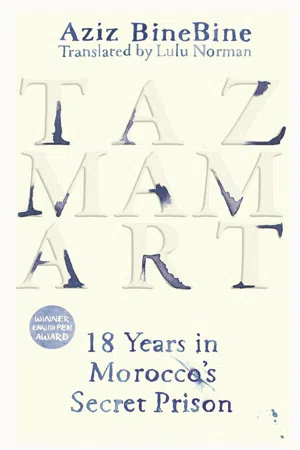

A memoir from a political prisoner in Morocco's notorious Tazmamart prison.

On July 10, 1971, during birthday celebrations for King Hassan II of Morocco, attendant officers and cadets opened fire on visiting dignitaries. A young officer, Aziz BineBine, arrived late and witnessed the ensuing massacre without firing a single shot, yet he would spend the next two decades in a political prison hidden in the Atlas Mountains—Tazmamart. Conditions in this now-infamous prison were nightmarish. The dark, underground cells, too small for standing up in, exposed prisoners to extreme weather, overflowing sewage, and disease-ridden rats. Forgetting life outside his cell—his past, his family, his friends—and clinging to God, BineBine resolved to survive. Tazmamart: 18 Years in Morocco's Secret Prison is a memorial to BineBine and his fellow inmates' sacrifice. This searing tale of endurance offers an unfiltered depiction of the agonizing life of a political prisoner.

On July 10, 1971, during birthday celebrations for King Hassan II of Morocco, attendant officers and cadets opened fire on visiting dignitaries. A young officer, Aziz BineBine, arrived late and witnessed the ensuing massacre without firing a single shot, yet he would spend the next two decades in a political prison hidden in the Atlas Mountains—Tazmamart. Conditions in this now-infamous prison were nightmarish. The dark, underground cells, too small for standing up in, exposed prisoners to extreme weather, overflowing sewage, and disease-ridden rats. Forgetting life outside his cell—his past, his family, his friends—and clinging to God, BineBine resolved to survive. Tazmamart: 18 Years in Morocco's Secret Prison is a memorial to BineBine and his fellow inmates' sacrifice. This searing tale of endurance offers an unfiltered depiction of the agonizing life of a political prisoner.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tazmamart by Aziz BineBine, Lulu Norman in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781912208890Subtopic

Social Science BiographiesI dreamed of being a journalist or a filmmaker; I became a soldier. The son and grandson of court officials, I became a revolutionary despite myself. I was a playboy; I became a convict. But as the saying goes, man proposes and God disposes.

My mother was the daughter of an Algerian captain in the French army. He had arrived in Morocco between 1912 and 1915 with the protectorate army that had come to pacify the country, and he was appointed liaison officer working with indigenous peoples – a role that cost him his life. He was poisoned by high-ranking Moroccans afraid that this soldier – French, Arab and a Muslim, just like them – might take their place. He died serving France: a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur, he was awarded the Military Medal, the Croix de Guerre, the Medal of Merit and so on. My mother was eight years old and became a ward of the state; at eighteen, she married my father. A musician’s son, he was living at the court of El Glaoui,* the famous pasha of Mar-rakech, and was his most loyal companion.

My father was an ulema, one of those learned keepers of faith and religious expertise in an Islamic country where religion and reasoning have always been intertwined and are still great sources of power and wealth, especially when developed under the protective, expansive wing of the ‘Prince’.

My father maintained this status quo.

His learning and extensive cultural knowledge had singled him out early to serve the country’s greatest men: first El Glaoui and then King Hassan II, to whom he became very close. Having no official duty other than keeping the sovereign company, he would see him day and night, in privileged, intimate moments when the king was at his most relaxed and receptive. Owing to his phenomenal memory and his eloquence, my father had studied literature and Islamic law at the same time. He could quote the finer points of civil or Islamic law, had learned the manuals of Arabic grammar and rhetoric by heart and, as well as Arabic, had perfect command of Berber and French. To cap it all, he had set about memorising all Arabic poetry from the pre-Islamic era onwards. As a young man, he’d been friends with one of the greatest Moroccan poets, Ben Brahim, the ‘poet of the Red’, who owed this honorific to the colour of his native city, Marrakech. But Ben Brahim could only compose his most beautiful poetry when he was blind drunk. Unfortunately, the morning after, all or part of his creation had evaporated with the fumes of alcohol. To remedy this, he would ask my father along – who didn’t join in the carousing – and the following morning Ben Brahim would come to buy his own poems from him. Having heard them just once, my father had memorised them. When he met my mother, it was love at first sight; he married her, carefully refraining from admitting to the modern young woman that he already had a first wife.

Until the age of sixteen, I was French through my mother. When Algeria gained its independence in 1962, she opted for Moroccan nationality, which was a prerequisite for her application to be a tax inspector. I took my father’s nationality as a matter of course; he was Moroccan born and bred, equally at home in Berber and in Arab culture, since his heritage fused the two. When, after taking my baccalaureate, the moment came to choose a career, the easiest solution was to sit the exam for the Royal Military Academy. Since I was part of the very first intake of baccalaureate-holders to this prestigious institution, I became an officer, to my mother’s great pride. A pride that would be short-lived, so fate had decreed: a trivial incident, an act of student bravado that in the first instance placed us at the mercy of Colonel Ababou, would alter our lives dramatically, making us protagonists in the darkest act of our country’s recent history.

In 1970, at the end of our final year at the academy, we were entitled to some leave, as had been the custom for generations, but for no good reason the director decided to cancel it, sending us instead on an utterly pointless course in mechanics. We considered this a gross injustice and promptly abandoned the course. When we returned the following term, instead of being posted to different army corps – which was what usually happened – our year and the one above were assigned to Colonel Ababou, a man with a reputation for brutality, as a disciplinary measure. We were seconded to Ahermoumou as instructing officers.

Ahermoumou is a small village in the Middle Atlas, huddled at the foot of Jebel Bou Iblan. Winters there are harsh and snowy and the summers extremely hot. The military school was just outside the village on a plateau overlooking an immense sheer cliff, constantly pummelled by the wind. It housed around two thousand cadets as well as the staff and their families. This community sustained the village and was expertly run by Colonel Ababou, assisted by loyal NCOs tasked with managing the barracks. The officers – in this case, us – took care of the teaching.

In Ahermoumou, discipline was ironfisted – for the cadets as well as for staff, whether they were officers or not. No favouritism was shown, even to those soldiers closest to the colonel. In fact, they were the most fearful of all, since they were in the front line and had more to lose. Not all his men were on a level, however; besides the administrators, a group of henchmen were assigned the dirty work. They were a real mafia, devoted body and soul to their master and led by the infamous warrant officer first-class Akka, who was Ababou’s eyes, ears and right hand.

Discipline might have been severe, but the advantages were enormous, and we knew it; when they felt the need, our superiors were only too ready to remind us. Most of us had escaped a nasty punishment, we were put up rent-free in beautiful villas, ate for nothing in the mess and had all the military kit we needed, none of it itemised and with no obligation to return or reimburse it should it be damaged or lost.

Time passed in Ahermoumou as we began to learn about life, about power and responsibility, both in Morocco and within the army. Schoolbooks had taught me that a military career was about ‘glory and servitude’, when in fact it was glory for the few and servitude for everyone else – if that can be called glory.

We were getting used to authority and discipline. Not everything was black and white; we had to learn the importance of nuance, there being so much of it in our country. Above all, we needed to learn hypocrisy, which was as vital to someone making a career in the army administration as swimming is to a sailor. In this, we had a great master, the grand champion of illusionists and tricksters: Ababou. He’d built a legend around himself in the Royal Armed Forces, according to which he was a kind of Joha* or Ali Baba – a brave-hearted thief at the head of a dedicated commando unit, whose mission it was to scour Fez and the surrounding countryside and seize equipment from communities, businesses or private individuals. Anything that might be lying around and could prove useful for the garrison, or for reinforcing infrastructure on the colonel’s farms, was fair game. I wouldn’t be surprised if heads of cattle came into it, too. Their audacity was boundless. Unscrupulous men were highly valued at the time; lack of conscience was seen as courage, highway robberies were feats of arms. They were admired, feared and often idolised rather than hated. Attracted to power like flies to honey, these lords grovelled lower than anyone else, the better to bite when the moment came. They knew each other, socialised together and kept a close watch on one another, attempting all the while to conceal their teeth and claws.

The colonel was a short, rather chubby man whose pudgy face drew attention to his cold, hard stare. He ruled by force, stopping at nothing, and woe betide anyone who stood in his way, because Ababou never forgot a grudge. No doubt it was this resentment that drove him to the insanity of the putsch, which would mean ruin for him and for us. He was furious with the entire world for his having been born small and poor – which was only partly true since the Ababous were an eminent family that had once counted a vizir among them. During the protectorate, the colonel’s father was himself a sheik* under the command of Caid Medbouh. Medbouh’s son – the famous General Medbouh – would be our man’s chief supporter and, more importantly, the mastermind behind his attempted coup. Excel though he might, Ababou would remain Medbouh’s subordinate. Every time he stood before the general, decades of stifled resentment stirred within him. His fateful enterprise proved how desperately he dreamed of one day having not just the Medbouhs but many others under his command – and why not be rid of the king himself…? One day, he would be lord and master… And he was certainly up to the job. One of the best in his year at the Royal Military Academy, and the very best at the officers’ training school, he had succeeded brilliantly in his exams at the École de Guerre in France. This earned him the honour of directing the armed forces’ general manoeuvres in Marrakech in 1968, in the presence of King Hassan II himself. During these combat drills, which involved the entire army, each unit had to act according to very precise, predetermined orders so as to support or fight other units, depending on whether they were acting as allies or enemies. Live ammunition or blanks might be used in these exercises: a formidable trap. Ababou represented the new generation of officers to emerge from that very young Moroccan army, of which he was such a talented member. As the outstanding laureate of the École de Guerre, he was the first officer of that generation to direct manoeuvres on a national scale and perhaps, one day, he would be commander-in-chief of the army. The tiniest blunder could bring his career crashing down. The test was more than conclusive: he received the compliments of the king and the entire military command. That day a new leader was born and with him, perhaps, a lust for power that would jolt the Moroccan political and social system from its torpor.

* Thami El Glaoui, pasha of Marrakech 1912—1956, was one of the world’s richest men. Hugely powerful in Morocco, he helped the French to overthrow Mohammed V.

* A mischievous joker of popular legend.

* Tribal authority, an agent (unconnected to Middle Eastern sheiks).

It was during similar manoeuvres in El Hajeb, not far from the Ahermoumou training school and its Sefrou annex in particular, that Colonel Ababou and General Medbouh’s first attempt at a coup was planned to take place. At that time, the Sefrou cadets and their officers were detailed to take part in manoeuvres at El Hajeb, with some reinforcement from us. I was not one of the personnel involved. Everything was ready: the commando unit had been assembled and the infantry were standing by with their vehicles, weapons and ammunition. At the last minute, the order came to break ranks because the school’s participation had been called off. We would find out later, after the events at Skhirat, that the king – having caught wind of something, or simply put off by bad weather – had decided against attending. The plan fell through but was only postponed, because, on the morning of the 9 July 1971, we received the order to prepare for live firing exercises the next day at Benslimane, a few kilometres from the palace at Skhirat.

We had the whole day to prepare, to assemble our units, do the roll call, check kit and ensure that supplies, weapons and ammunition were correctly distributed. The mission was a delicate one, as the men had no experience of live firing exercises. In fact, they had no experience at all – most of them hadn’t been in the army six months. Worse, no officer had command of his own cadets that day.

By evening, everything was ready. The drill had been rehearsed a few months earlier, but with different actors; this time, the finger of fate pointed to us. After a hard day’s work, we gathered for supper in the officers’ mess, in combat uniform ofcourse, with guns and ammo. As he entered the mess, the school’s doctor, a young French lieutenant doing his military service, exclaimed: “My God, you look like you’re planning a coup!” A burst oflaugh-ter greeted his remark, but a seed of doubt had been sown.

The next day, every man was at his post. The convoy set off early in the morning. It consisted of twenty or so trucks loaded with men, each led by an officer and an NCO. At the front and back of the convoy were what we referred to as the commandos: light armoured jeeps, some equipped with heavy 12.7mm machine guns and others with anti-tank ammo. There were four soldiers to each jeep, most of them the colonel’s men. Later we learned that some of these light units had been given special instructions: to ensure that no soldier or vehicle deviated from the plan. They had orders to shoot anyone who might take it into their head to go walkabout.

The convoy drove the three hundred kilometres from Ahermoumou to Rabat with no difficulty, without once being stopped by gendarmes, police or any kind of roadblock – which in our country is strange to say the least. A few kilometres outside Rabat, near the small town of Sidi Bouknadel, the convoy came to a halt at the edge of a forest. Only the officers had orders to disembark. Ababou was waiting for us with his brother Mohamed, who was older than him but in no way his equal. There were other people, NCOs we’d never seen before. Later we’d find out they were members of his family. He briefed us on the next part of our mission: the unit would divide into two convoys, one under his command and the other under his brother’s. Each convoy would go in through one gate, disembark and scatter down the alleys, shooting only on command and preventing anyone from ‘coming out’.

But coming out of where?

A crucial point needs making here as regards the location of the action, about which my comrades and I disagreed. Personally, I’d heard the word ‘palace’. Some claimed to have heard ‘drill grounds’ and others agreed with ‘palace’ but with the understanding that the king was in danger. Where did not the truth but reality lie? Often, time and events distort our memory of the facts.

Destiny had shown her hand; all the players in this drama would be mown down. No one would come out of it unscathed.

Skhirat palace was the king’s summer residence, where, on his birthday every year, the Festival of Youth was celebrated. Anyone who was anyone in the country’s political, diplomatic, military and business worlds would gather around the sovereign on that day. Gendarmes and soldiers from the Royal Guard were on duty at the palace gate. Seeing the convoy, they raised the barrier and stood to attention. We entered, unaware that our orders were entirely fictitious and the king knew nothing of the operation.

We burst onto two avenues which marked the palace boundaries to the north and south. Between them stretched a golf course, a vast expanse of lawn dotted here and there with isolated thickets and a few lone trees, where the king’s celebration was taking place: a magnificent, animated cocktail party, a meeting of the country’s elite. Behind them stood a long building, a series of state rooms, which at the north end overlooked the royal apartments and their outbuildings. The western façade was punctuated by huge, glazed bay windows that overlooked a private beach. The eastern façade, which gave onto the golf course, was completely shuttered. The configuration of the grounds partly accounts for the massacre that took place that day.

The first lesson in fighting that we would give our cadets was that, in the event of ambush, under enemy fire, they must jump out of the truck and return fire. Unhappily, this instruction was applied to the letter.

The convoy led by Ababou’s brother entered first, by the northern gate; he arrived facing the golfing green, where the king’s many guests were assembled. We were on the other side, preparing to disembark, when we heard a burst of gunfire. Yet no order had been given. Had one of the younger cadets panicked? It remains a mystery. The rout had begun. Following their training, the cadets jumped from the trucks and all of them opened fire. We tried everything to stop them, but it was no use; all we could do was fall flat on our stomachs to avoid stray bullets. A barrage of fire erupted from the two columns of trucks that surrounded the area; it was a two-way massacre. The people still standing on the golf course were mown down in the crossfire, along with many of the cadets. The exact number wasn’t revealed after the events, but more than two hundred were felled by their own comrades.

Now it was complete chaos. No one was in charge of anyone, no one knew what to do; Ababou himself had completely lost control of the situation and had been shot in the shoulder the moment he jumped down from the truck. I’d seen cadets fall right in front of me and I couldn’t even tell if they were from my unit. I was utterly helpless. I yelled, but it was no use, no one was listening. I wanted to – I should have – called their names, but I didn’t know them. By assigning us cadets that weren’t our own, they’d limited our ability to act. And it was a disaster.

The shooting stopped; the tumult co...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle

- About the Author

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

- Chapter 23

- Chapter 24

- Chapter 25

- Chapter 26

- Chapter 27

- Chapter 28

- Chapter 29

- Chapter 30

- Acknowledgements