- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Fronted by one of the world's most iconic doors, 10 Downing Street is the home and office of the British Prime Minister and the heart of British politics. Steeped in both political and architectural history, this famed address was originally designed in the late seventeenth century as little more than a place of residence, with no foresight of the political significance the location would come to hold. As its role evolved, 10 Downing Street, now known simply as 'Number 10,' has required constant adaptation in order to accommodate the changing requirements of the premiership.

Written by Number 10's first ever 'Researcher in Residence,' with unprecedented access to people and papers, No. 10: The Geography of Power at Downing Street sheds new light on unexplored aspects of Prime Ministers' lives. Jack Brown tells the story of the intimately entwined relationships between the house and its post-war residents, telling how each occupant's use and modification of the building reveals their own values and approaches to the office of Prime Minister. The book reveals how and why Prime Ministers have stamped their personalities and philosophies upon Number 10 and how the building has directly affected the ability of some Prime Ministers to perform the role. Both fascinating and extremely revealing, No. 10 offers an intimate account of British political power and the building at its core. It is essential reading for anyone interested in the nature and history of British politics.

Written by Number 10's first ever 'Researcher in Residence,' with unprecedented access to people and papers, No. 10: The Geography of Power at Downing Street sheds new light on unexplored aspects of Prime Ministers' lives. Jack Brown tells the story of the intimately entwined relationships between the house and its post-war residents, telling how each occupant's use and modification of the building reveals their own values and approaches to the office of Prime Minister. The book reveals how and why Prime Ministers have stamped their personalities and philosophies upon Number 10 and how the building has directly affected the ability of some Prime Ministers to perform the role. Both fascinating and extremely revealing, No. 10 offers an intimate account of British political power and the building at its core. It is essential reading for anyone interested in the nature and history of British politics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access No. 10 by Jack Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Building

It is the smallest, yet the greatest street in the world, because it lies at the hub of the gigantic wheel which encircles the globe under the name of the British Empire.

– Joseph Hodges Choate1

On first inspection, No. 10 Downing Street appears an unassuming home for the British Prime Minister. Yet despite its outward appearance, this modest terraced property located just off Whitehall in London’s SW1 postcode is a house like no other. Behind one of the world’s most iconic front doors lies a sprawling, labyrinthine building with an incredible history. No. 10 has been the property of the First Lord of the Treasury, a role that in modern times has become synonymous with that of Prime Minister, for nearly 300 years.

Constructed in the 1680s, this historic building has remained a constant at the heart of British governance ever since. At the time of John Major’s departure from No. 10 in 1997, it had seen fifty different Prime Ministers come and go. Since Arthur Balfour established the precedent at the turn of the twentieth century, every subsequent Prime Minister has at some point made Downing Street their home. Alongside its residential role, No. 10 also serves as a twenty-four-hour office for the Prime Minister and their staff, as well as a venue for entertaining prestigious national and international guests.

This historic terraced London house has endured stoically through the rise and fall of the British Empire, two world wars and countless diplomatic, political and economic crises. It has transitioned from the Industrial Revolution to today’s high-speed, open-all-hours information age, and has accommodated technological change from the installation of electric lighting to the dawn of email.

Downing Street has also seen the world transformed around it. Its namesake was a former resident of the puritan colony of Massachusetts; it was at Downing Street, just short of a century later, that Prime Minister Frederick North, better known as Lord North, would receive the news that the American colonies were lost.2

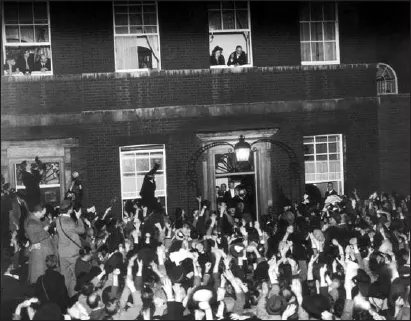

It was from an upstairs window of No. 10 that Neville Chamberlain would proclaim ‘peace for our time’ to the assembled crowd in Downing Street in 1938, and it was within this same building that Winston Churchill’s War Cabinet would decide to fight on against Adolf Hitler in May 1940. Five years later, Churchill would broadcast the end of the war in Europe from No. 10’s Cabinet Room, and his successor, Clement Attlee, would subsequently announce the surrender of Japan from the same spot. Both Benjamin Disraeli’s acquisition of the Suez Canal in 1875, and Anthony Eden’s reluctant acceptance of its loss following the humiliation of the 1956 crisis, were directed from No. 10.3

Protesters have marched on Downing Street throughout its long history. The street was generally accessible to the public until security gates were erected at the Whitehall end in 1989, and protesters have thrown rocks at No. 10’s windows on numerous occasions. Suffragettes chained themselves to its railings. Large wooden barricades were erected at the end of the street in the early 1920s as a security measure in response to the Anglo-Irish War. Less could be done when Zeppelins dropped bombs ‘alarmingly near’ to No. 10 during the First World War; German bombs would cause substantial damage to the building itself during the Second World War.4 An Irish Republican Army (IRA) mortar also left its mark in 1991, landing in No. 10’s garden during a meeting of the War Cabinet to discuss the Gulf War, exploding just after the Prime Minister had said the word ‘bomb’.5

Throughout all this turmoil and transformation, No. 10 has remained remarkably consistent. Familiar and iconic, the building has provided an abiding presence in a rapidly changing world, remaining fundamentally the same over the years despite the constant evolution of Britain’s politics and place in the world. No. 10’s appearance and operation have been essentially unchanged, despite the transformation of its surroundings. It even survived the construction of George Gilbert Scott’s Foreign Office (which became the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in 1968) on the other side of Downing Street in the 1860s, which dwarfed No. 10 in both scale and grandeur. No. 10’s notable architecture and world-famous front door remain a significant selling point across the world. So popular was the iconic door that a private company approached the government in the 1950s, seeking to manufacture replica ‘No. 10’ front doors for sale to American tourists. The Ministry of Works perhaps unsurprisingly decided to reject the request, however, believing that ‘this would, to some extent, detract from the dignity of the residence’.6

Neville and Anne Chamberlain look out an upstairs window at crowds assembled on Downing Street to celebrate the ill-fated Munich Agreement, September 1938. Sadly, the ‘peace for our time’ declared by Chamberlain would prove short-lived.

Despite its role at the heart of British government, No. 10 was not designed for its current purpose. The Downing Street houses were built cheaply, with the intention of turning a profit for their developer, and were certainly not designed or intended to house the most powerful politicians in Britain. They have been repeatedly, incrementally adapted and refurbished, with only one serious and total reconsideration in their history. Their blend of resilience and adaptability with a reliance on precedent and tradition echoes that of British government and the Westminster system as a whole.

There are great lessons to be gleaned from the study of No. 10. The building’s story is intimately intertwined with the stories of its occupants. The interaction between No.10’s many historic residents and the building that they have temporarily occupied is revealing of their personalities and their approaches to occupying the office of Prime Minister. But, above all, the history of No. 10 is fascinating and unique.

Living at No. 10

What have the building’s historic residents made of No. 10? The house has had more than its fair share of compliments from those who have occupied it over the years. William Pitt the Younger, during his first stay at No. 10 as Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1782, wrote to his mother describing his new residence as ‘the best summer town house possible’.7 Over 150 years later, postwar premier Clement Attlee would report settling into No. 10 easily, describing the house, with typical understatement, as ‘very comfortable’.8 Clarissa Eden, wife of Attlee’s successor-but-one, Prime Minister Anthony Eden, thought No. 10 was ‘the loveliest house in London’.9 The Conservative Prime Minister Harold Macmillan praised No. 10 in his diary, noting that the building was ‘rather large, but has great character and charm. It is very liveable’.10

The house is not just a home, but a centre of British national life. Olwen Carey Evans, daughter of the First World War Prime Minister David Lloyd George, recalled her time at No. 10 fondly: ‘There was always something going on. Famous people came and went, and No. 10 seemed to be the hub of the universe.’11 Macmillan echoed these sentiments, noting that the building had long been ‘famous throughout the whole world as the hub or centre of British rule and influence’.12 As one historian of the premiership describes, ‘All the power lines lead to No. 10.’13 Life at No. 10 is therefore rarely dull for those who live and work there.

British understatement?

No. 10’s air of calming humility has been widely noted. As the building is a venue for national and international decision-making at the highest level, the weight of the world can often bear down heavily upon its shaky foundations. However, No. 10 is a stoic, even tranquil place. Churchill’s Private Secretary John ‘Jock’ Colville described life at No. 10, even during the great strain of the Second World War, as a ‘gentlemanly occupation’. Colville’s No. 10 was ‘a well-established private house of pre-war comfort’, within which ‘coal fires glowed in every grate, at the tinkle of a bell were ivory hairbrushes and clean towels in the cloakroom; and everything reminded the inhabitants that they were working at the very heart of a great empire, in which haste was undignified and any quiver of the upper lip unacceptable’.14

In addition to the air of relaxed professionalism, the relative modesty of the building, particularly when compared with other similarly purposed buildings internationally, is also charming. Joe Haines, Press Secretary to the Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson, observed that the modest façade of No. 10 masked the incredible power that lay within:

From the street outside it is a classic example of British understatement, hiding the treasures of art and history and experience that are within… Today it harbours only Britain’s crises, but it was once the eye of the storms that shook the world.15

The contrast between the Downing Street terrace and the notably larger and significantly grander Foreign and Commonwealth Office building across the road is stark. Writing in 1908, the author Charles E. Pascoe observed the unusual contradiction between the two buildings’ outward appearances and the significance of the functions that they housed:

The First Lord’s residence is overshadowed by the statelier glories of the Foreign Office opposite. That imposing pile may rear its grand front over against the humbler dwelling; it may make parade of its fine archway and inner court; it may boast its sumptuous conference room, its richly decorated apartments of State, its noble halls and stairways, its painted ceilings and the rest; but not one of the grand rooms has a tithe of the interest that belongs to the smallest chamber in that little house fronting it. A dingy little dwelling in sober truth […] unknown to the millions of London, save by repute, whose history should be richer in anecdote and reminisce, could all be written down, than that of any building owned by the Crown.16

A place in history

The sheer historical importance of the decisions that have been made in No. 10 continues to make an impression on its occupants. Macmillan argued that the building had ‘a meaning and a significance’ which was essential to preserve.17 Margaret Thatcher observed that ‘All Prime Ministers are intensely aware that, as tenants and stewards of No. 10 Downing Street, they have in their charge one of the most precious jewels in the nation’s heritage.’18 For Thatcher, the portraits and busts of past Prime Ministers that decorated No. 10’s otherwise unremarkable interior reminded the current occupant of the 250-year path of history onto which they now stepped.19

Thatcher’s speech-writer Ronald Millar felt that this sense of history seeped not just from No. 10’s ornaments and decorations but from the very walls of the building itself. Noting the building’s plainness, Millar claimed that No. 10 ‘acquires a wonder and a magic’ for those who know and consider the stories of the people who have ‘run Britain from those premises and more than once saved it from its enemies’:

And if you walk down its long corridor from the black front door to the white one at the end of that corridor which opens to the Cabinet Room, and stand in the doorway and look about you and remember those who have sat and taken the big decisions […] why, then you’re a dull stick if you are not stirred and humbled by the experience, for you are standing in the engine room of our country’s history.20

Peter Hennessy has also noted that, alongside its calmness, the thing that strikes visitors to No. 10 is ‘the near tangible feeling of a deep and richly accumulated past whose resonance is such that the walls almost speak’.21

The rabbit warren

Some have spoken of the historic building’s cramped conditions in fond terms. Harold Macmillan found that ‘one of the charms of the house lies in the number of small rooms which give a sense of intimacy’.22 Harold Wilson described it as ‘a small village’.23 Bernard Donoughue, Head of the No. 10 Policy Unit under Wilson, describes how the ‘cosiness’ of No. 10 meant that ‘there was little scope for hierarchy and standing on ceremony’.24 Whilst the relatively small building, with its maze-like corridors and disorientating layout, can seem like an inconvenient place from which to run a government, its humbleness and intimacy can also make for a warm, welcoming and ultimately nimble operation.

There are, of course, alternative viewpoints. Henry Campbell-Bannerman, Liberal Prime Minister from 1905–8, described a ‘rotten old barrack of a house’; his wife Charlotte ‘a house of doom’.25 Perhaps this is unsurprising, considering that Campbell-Bannerman was the only Prime Minister to die at No. 10. Margot Asquith, wife of Campbell-Bannerman’s successor, Herbert Henry Asquith, recalled waiting outside in the car whilst her husband visited his ailing predecessor inside the building that would soon become their home: ‘I looked at the dingy exterior of Number 10 and wondered how we could live there.’26

Margot Asquith did not subsequently warm to the labyrinthine property: ‘It is an inconvenient house with three poor staircases […] and after living there a few weeks I made up my mind that owing to the impossibility of circulation I could only entertain my Liberal friends at dinner or at garden parties.’ To make matters worse, taxi drivers seemed not to know the address: ‘10 Downing Street ought to be as well known in London as Marble Arch or the Albert Memorial, but it is not.’27

As Margot Asquith observed, the unusual and complex layout of the Downing Street houses was far from convenient. In fact, her son Anthony and Chancellor Lloyd George’s daughter Megan once both went missing within the house. Due to fears of abduction by Irish nationalists or disgruntled suffragettes, the police were called, before the children w...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle

- FM

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 The Building

- 2 What Goes On Inside No. 10 Downing Street

- 3 The Geography of Power at No. 10 Downing Street

- 4 The geography of Whitehall – and Geography Subverted

- 5 Reconstructing No. 10 Downing Street

- 6 Living above the Shop

- 7 Hosting the world

- 8 No. 10 under attack

- 9 New Labour at No.

- 10 Concluding Thoughts

- Image Credits

- Notes

- Index