eBook - ePub

Balfour

About this book

Prime Minister known for announcing "that Britain favoured a homeland for the Jewish People in Palestine."

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

eBook ISBN

9781912208371Subtopic

Political BiographiesPart One

THE LIFE

Chapter 1: A Man Born to Rule

Arthur Balfour, as an MP, senior politician, Cabinet Minister and then Prime Minister was a perfect social representative of the late-Victorian Conservative political elite. In terms of his own social status he was a patrician. He was a scion of a wealthy, landed Scottish family and inherited extensive estates at Whittingehame, where he was born on 25 July 1848, and Strathconan. Even the railways acknowledged his and his family’s status, for the line from Edinburgh that passed Whittingehame had a stopping point named ‘Balfour Halt’, which enabled Balfour to be met and more easily transported to his favourite country seat. Furthermore, in 1870 he purchased a large town house in Westminster – an essential prerequisite for membership of ‘Society’ and political society in particular.

Equally important, Balfour was the nephew of the 3rd Marquis of Salisbury (the Conservative leader c. 1884 – 1902) and he was thus part of the close-knit Conservative political hierarchy that found its focus at Salisbury’s country seat at Hatfield House in Hertfordshire. This political coterie, which came to be known as the ‘Hotel Cecil’ (for the simple reason that, either by birth or marriage, most of its members were in the Cecil family), represented the apogee of the Tory hierarchy. Balfour was thus almost born to inherit the Prime Ministerial ‘purple’.

His early years were dominated by his mother, Lady Blanche, a daughter of Lord Salisbury. She acted as a quasigoverness in terms of his early education, although he also attended Hoddesdon Grange Prep School in Hertfordshire. As a teenager he attended Eton, although he was not particularly happy there, and from there went up to Trinity College, Cambridge. Balfour secured an indifferent degree result – he obtained a Second instead of the First he had hoped for and expected. This may have been due to the fact that he had developed an aversion to writing by hand, which was to remain with him throughout his life and which was hardly helpful when it came to examinations. Nevertheless, he gained the respect of one of his tutors, the philosopher Henry Sidgwick, and was also influenced in terms of both religious and economic thought, by the College’s Clerical Dean and Tutor in Moral Sciences, the High Churchman and historical economist William Cunningham. Balfour’s voracious reading and his close relations with celebrated tutors in philosophy earned him a reputation for studied ‘high-mindedness’, and this in turn helped earn him to gain the College nick-name ‘Pretty Fanny’, which satirised his bookish and scholarly predilections.

It was Balfour’s family connections that provided him with his entry into parliamentary politics, for he was returned, unopposed, as Conservative MP for Hertford in February 1874 – Hertford being a constituency where the chief local political potentate was Balfour’s uncle, Lord Salisbury. During his first six years in the Commons Balfour made little impact. He was, in part because of his social rank and connections, respected, and he was generally liked and viewed as ‘clubbable’. But apart from some contributions to debates on obscure religious questions, and even more obscure economic issues, he made few speeches in Parliament. Indeed, the relatively abstruse nature of his interventions appeared to confirm the ‘high minded’ reputation he had gained as a student at Cambridge, as did the fact that most of his energies seemed to have been devoted to writing his Defence of Philosophic Doubt, which was published in 1879.

In this work, Balfour sought to offer a defence of scepticism against what he saw as the prevailing philosophical trend of scientific naturalism. For Balfour, who was deeply religious, only sceptical questioning could provide a basis for true faith, which was beyond scientific reason and which, in 1895, he was to outline as the Foundations of Belief. Politically his philosophy was interesting as an insight into his mode of thought, but it served him little in his career in Parliament. His colleagues, especially his uncle, respected his intellect, but for most backbenchers he was perhaps the first of a line of senior Tories who were ‘too clever by half’, as in 1961 Lord Salisbury’s grandson famously damned the Colonial Secretary Iain Macleod. In the late 1870s a hard-headed parliamentarian rather than a ‘philosopher-king’ would have seemed more useful to a party that faced difficult political situations on both the domestic and imperial fronts, for taxes had risen to unpopular levels in order to finance costly imperial adventures, notably in Southern Africa.

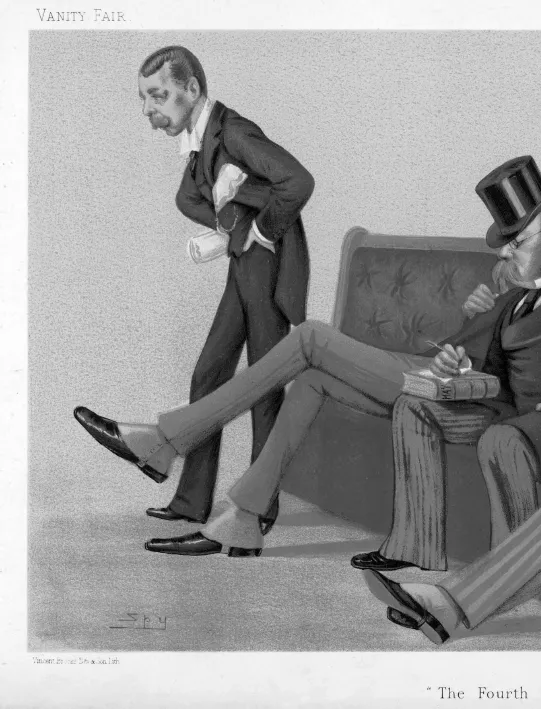

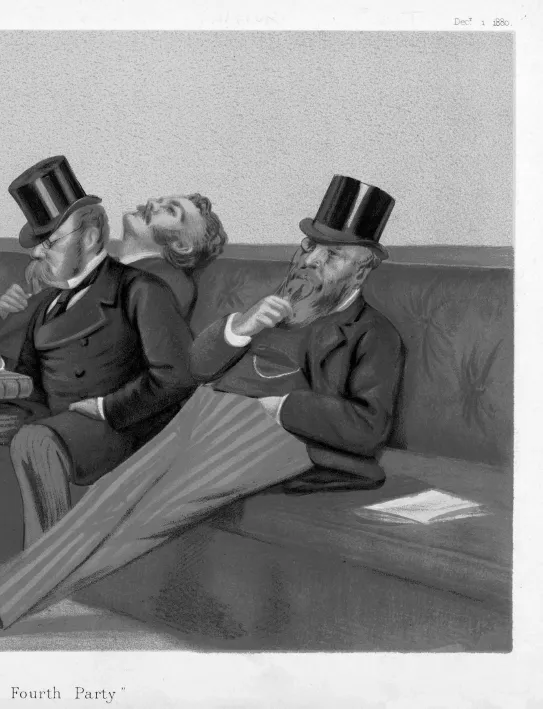

It was in the early 1880s that Balfour’s political reputation began to take off. Following the Liberal victory at the 1880 General Election, and Disraeli’s death in April 1881, the Conservative Party and its leadership in particular were in some disarray. Not all Conservatives would have accepted Disraeli’s epigrammatic conclusion that their Party could only ‘die like gentlemen’, but many Conservatives saw the political situation as grim. It was in these circumstances that Lord Randolph Churchill emerged as a Conservative political hero, with a series of rhetorically invigorating Parliamentary attacks on Gladstone and his administration and also through his mobilising of local Conservative constituency activism with his vague, but politically exciting notion of ‘Tory Democracy’. Balfour played very little role in shaping or promoting Tory Democracy’, but in the Commons he joined with Churchill, Henry Drummond-Wolff and John Gorst as a key member of the so-called ‘Fourth Party’, which carried out a form of Parliamentary ‘guerrilla warfare’ against the Liberals in Commons debates and energised an otherwise demoralised Conservative Party. For Churchill the ‘Fourth Party’ and ‘Tory Democracy’ were key elements in his attempt to promote his own political career and establish his credentials as a possible future Conservative leader. Balfour’s priorities were, however, very different. His membership of the ‘Fourth Party’ undoubtedly served to enhance his parliamentary reputation, but his underlying political objectives were to quieten party discontents rather than, as in Churchill’s case, exploit them for personal ends.

Lord Randolph Churchill (1849–95), the father of Winston Churchill entered Parliament as a Conservative MP in 1874, and advocated a progressive conservatism called Tory Democracy which favoured popular social and constitutional reform. An effective orator, he opposed Home Rule for Ireland and famously coined the phrase ‘Ulster will fight and Ulster will be right’. He became Secretary of State for India (1885–6) in Lord Salisbury’s first government and Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons (1886–7) in his second. When the Cabinet rejected his budget proposing cuts in the armed services, he resigned, and never again held office. He died of syphilis at the age of 45.

Churchill’s political strength in the early 1880s was a result of the fact that there was a core of discontent within the Conservative Party among the new, urban and suburban Tory elites who, since the founding of the party’s National Union of Conservative Associations (NUCA) in 1867, had provided the key voting and organisational basis of local Conservative activity in borough seats. These ‘new’ Tories, who came to be known as ‘Villa Tories’, were resentful about the way they had been condescendingly treated and even ignored by the party’s aristocratic hierarchy in the 1870s. The fact that John Gorst, the Chief Agent of the National Union, had resigned his party post and joined the ‘Fourth Party’ was a most eloquent expression of the depth of this ‘Villa Tory’ resentment. Intriguingly, Salisbury and Balfour seemed to appreciate the socio-political power-base of Churchill’s position better than he did. Certainly, Salisbury and Balfour worked assiduously to ensure that these ‘Villa’ discontents were assuaged. It was Salisbury as Prime Minister who was primarily responsible for appeasing ‘Villa’ or Conservative middle-class sentiment. His primary tool was the Honours system, which he used systematically to grant knighthoods and other lesser ‘baubles’ to urban Tory notables. Perhaps the clearest evidence of the politically placatory role of the Honours system is the fact that almost half of Salisbury’s correspondence with the Party’s Chief Agent, R N Middleton, involved discussion of Honours and their most appropriate and politically useful recipients.

Naturally it was not possible to fulfil every request and/or hope for an honour. To have done so would have undermined the rationale of Honours, which were, after all, supposed to confer or confirm distinction. Furthermore, Honours may have been political recommendations but they were the gift of the monarch, and Queen Victoria did not always co-operate fully – in December 1898, for example, the Queen unilaterally cut the number of knighthoods and Orders of the Bath in the New Year’s Honours List by one-third, with the result, as Salisbury’s secretary noted, ‘that there will be many sore backs’. Furthermore, elevating an MP to a peerage could, depending on the timing, cause an awkward by-election, and, in terms of the prevailing protocols of status, the recipient of a baronetcy was expected to enjoy a particular income and social standing. But when faced with obstacles such as these the Conservatives found other lower-order rewards to offer their supporters and activists.

The Primrose League, which had been created in the early 1880s as part of the ‘Tory Democratic’ apparatus of the period, has been viewed as part of an institutional attempt to foster popular, working-class participation in Conservative politics. This may have been part of the League’s rationale, but arguably it was just as important as a means of integrating urban Tory elites into the ‘social politics’ of Conservatism. The ‘officers’ of the local Primrose League ‘habitations’ tended to be a blend of local gentry and middle class, and many League meetings were not mass affairs but social and business engagements for local notables. It was doubtless for this reason that the League’s local officers were known as ‘Knights’ and ‘Dames’ – allowing them to enjoy such titles even though they did not qualify for the real thing.

Here the League’s involvement of upper and middle-class women took on a particular significance, for it provided a (suitably domestic) political role for Tory women, but also a political ‘Society’ which mirrored and reinforced male association in the upper echelons of Westminster politics and local Conservative associations and clubs. It seems that a key function of the Primrose League was to forge links not only between the Conservative Party and ‘the democracy’ but also to bond old and new Conservative elites who were seeking to control ‘the democracy’.

Another ‘participatory’ reward in the gift of the Conservative hierarchy was membership of the Carlton Club or, failing that, the Junior Carlton. A good example, one of many, of how this worked was provided by Salisbury’s son Lord Cranborne, then MP for Darwen, who told the Conservative Chief Whip in July 1886 that:

‘A Mr William Huntington, one of my constituents, is very anxious to get into the Junior Carlton … He is a county magistrate for Lancashire and rather an important man in Darwen – being a partner of Potter who stood against me in ‘85 and brother of Charles Huntington who really came out against me this time … William Huntington is, however, a Tory and supported me, but it would be very useful to confirm him in his faith. He is not, I take it, a very convinced Tory. I may add that the firm of Potter and Huntington is the most important firm in Darwen and influences a large number of votes.’1

All of the ingredients of the management of urban Toryism were discussed in this letter: a local notable from an essentially Liberal background, needing to be confirmed in the Conservative faith in order that his local influence would be committed to the Conservative cause – all this to be achieved by holding out a simple but vital symbol of political recognition and social acceptance.

The attempts made by the Conservatives to blend their traditional, landed and gentry support with their new, bourgeois ‘Villa’ supporters were assiduous and continuous. However, they did not always flow smoothly, for the simple reason that social tensions were often as prominent as harmonies. Thus in 1888 Balfour told the Conservative Chief Whip about a great idiot in my country, who … Is burning to become a member of the Carlton Club.2 Likewise, when Balfour suggested that the prominent Leeds businessman, W L Jackson, be made Postmaster-General he felt it necessary to tell Salisbury that Jackson has great tact and judgement – middle class tact and judgement I admit, but good of their kind. He justly inspires great confidence in businessmen and he is that rara avis a successful manufacturer who is fit for something besides manufacturing. Balfour concluded his ‘glowing’ appraisal with the comment that: A Cabinet of Jacksons would be rather a serious order no doubt, but one or even two would be a considerable addition to any Cabinet.3 As it happened Jackson entered the Cabinet, and in 1898 he was created Baron Allerton as a further reward for his, : albeit middle class, tact and judgement. Equally important, Jackson’s town, Leeds, where he was President of the Chamber of Commerce, was granted a City Charter and Lord Mayoralty by Salisbury’s second government, thereby confirming that it was the locale and not only a prominent individual that was being recognised and honoured.

He [the manufacturer W L Jackson] justly inspires great confidence in businessmen and he is that rara avis a successful manufacturer who is fit for something besides manufacturing.

BALFOUR

This glimpse at what one can best term the ‘social history of Conservative politics’ places Balfour’s parliamentary career in context. In late 1885, for example, he gave up his safe seat in the Salisburyian fiefdom of Hertford to became MP for East Manchester, which was a largely suburban constituency but which also contained, in its outlying districts, a substantial mining vote. Nor was Balfour the only Conservative grandee to locate himself in this manner, His brother Gerald took on a constituency in Central Leeds, whilst Salisbury’s sons Lord Cranborne, and Lords Hugh and Robert Cecil took on, respectively, Darwen and two metropolitan London constituencies. There was by no means overwhelming respect shown to middle class representatives by Tory grandees, but remarks such as those made by Balfour, cited above, were contained in private correspondence. In public the patrician hierarchy kept their snobberies and prejudices more than well contained. Salisbury, unlike his supposedly more populist-minded, or even demotic, predecessor Disraeli, always attended and addressed the annual NUCA conference. Furthermore, he set aside time to attend, for example, the South-Eastern Oyster Catchers’ Feast and the Sheffield Master Cutlers’ convention. Salisbury’s correspondence with his secretary indicates that he found such events extremely tedious, but he regarded his attendance as a socio-political necessity, and his nephew was wholly in accord with Salisbury on this point.

Robert Cecil, Lord Salisbury (1830–1902) was Prime Minister a total of three times (1885–6, 1886–92 and 1895–1902). In his view ‘The use of Conservatism is to delay changes till they become harmless’. He was against the tide of democratisation and social reform, opposing Factory Acts, temperance laws and leasehold reform. His expertise was in foreign affairs and for most of his time as Prime Minister he was also Foreign Secretary. A believer in ‘Splendid Isolation’, he nevertheless presided over a vast expansion of the British Empire in Africa, largely to forestall rival countries and to defend existing possessions, notably India and Egypt. (See Salisbury by Eric Midwinter, in this series.)

Balfour was first given office in Salisbury’s relatively shortlived first administration of 1885–6. He was not appointed to a Cabinet post, but was made President of the Board of Local Government. This was hardly a giant stride, but the period in which he held the post was important insofar as Balfour had to lay the foundations for the reform of local government in the counties. There was no immediate legislation – the issue was too complex and what parliamentary time there was too taken up with other matters. But Balfour’s proposals were to form the basis for the introduction of elected County Councils by Salisbury’s second administratio...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction by Francis Beckett

- Part One: The Life

- Part Two: The Leadership

- Part Three: The Legacy

- Notes

- Chronology

- Further Reading

- Picture Sources

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Balfour by Ewen Green in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.