- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

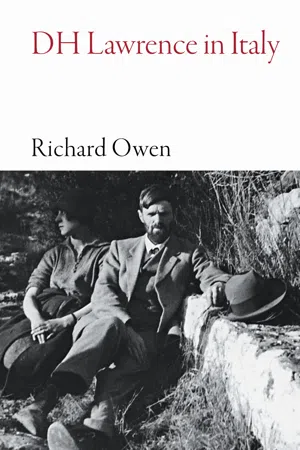

DH Lawrence in Italy

About this book

November 1925: In search of health and sun, the writer D. H. Lawrence arrives on the Italian Riviera with his wife, Frieda, and is exhilarated by the view of the sparkling Mediterranean from his rented villa, set amid olives and vines. But over the next six months, Frieda will be fatally attracted to their landlord, a dashing Italian army officer. This incident of infidelity influenced Lawrence to write two short stories, "Sun" and "The Virgin and the Gypsy," in which women are drawn to earthy, muscular men, both of which prefigured his scandalous novel Lady Chatterley's Lover.

In DH Lawrence in Italy, Owen reconstructs the drama leading up to the creation of one of the most controversial novels of all time by drawing on the unpublished letters and diaries of Rina Secker, the Anglo-Italian wife of Lawrence's publisher. In addition to telling the story of the origins of Lady Chatterley, DH Lawrence in Italy explores Lawrence's passion for all things Italian, tracking his path to the Riviera from Lake Garda to Lerici, Abruzzo, Capri, Sicily, and Sardinia.

In DH Lawrence in Italy, Owen reconstructs the drama leading up to the creation of one of the most controversial novels of all time by drawing on the unpublished letters and diaries of Rina Secker, the Anglo-Italian wife of Lawrence's publisher. In addition to telling the story of the origins of Lady Chatterley, DH Lawrence in Italy explores Lawrence's passion for all things Italian, tracking his path to the Riviera from Lake Garda to Lerici, Abruzzo, Capri, Sicily, and Sardinia.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access DH Lawrence in Italy by Richard Owen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & Literary Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Nottingham to Lake Garda

ON ONE OF THOSE SUNLIT, almost ‘summery’ days the Riviera can offer even in November, a train carrying DH Lawrence and his German wife Frieda pulled in with a hiss of steam at the resort of Spotorno.

So elated was the thin, red-bearded Lawrence to be back in Italy that he leant eagerly out of the carriage window as the train drew – 10 minutes late – into Spotorno station, within sight of the sparkling sea, the hotel-lined promenade and the beach. Rushing up the platform in a whirl of excitement came the woman he was looking out for: Rina Secker, the Italian wife of Martin Secker, Lawrence’s publisher, who had found them a villa overlooking the Mediterranean.

After a lifetime of restless travelling – New Mexico, Ceylon, Australia – intermittent ‘bronchial’ troubles (in reality, tuberculosis), and endless battles with censorship and prudery, Lawrence could breath a sigh of relief. He felt instantly at home. Rina embraced ‘DH’ while her parents, Luigi and Caterina, hung back shyly with the pram containing Rina’s baby son, Adrian.

Lawrence and Frieda’s luggage was collected and the party walked down to the seafront to enjoy a welcome glass of vermouth at the Capellero’s seaside hotel, the Miramare. A light breeze rippled the blue Mediterranean as the new arrivals admired the sand, the promontory and the island of Bergeggi just off the coast.

Up above them on the hill stood the Villa Bernarda, where Lawrence and Frieda would spend the next six months. They could have had little idea of the drama awaiting them. ‘It’s a nice old house sticking up from the little hill, under the castle, just above the village and the sea’, Lawrence wrote when he saw the villa shortly after arriving. It was 1925, Lawrence had just turned 40, and he was in a state of rare bliss.

‘The sun shines, the eternal Mediterranean is blue and young, the last leaves are falling from the vines in the garden. The peasant people are nice, I’ve got my little stock of red and white wine – from the garden of this house – we eat fried chicken and pasta and smell rosemary and basilica in the cooking once more – and somebody’s always roasting coffee – and the oranges are already yellow on the orange trees. It’s Italy, the same forever, whether it’s Mussolini or Octavian Augustus.’

Sunshine, sparkling sea, abundant wine, pasta with herbs, and someone ‘always roasting coffee’ – it is a picture you can almost smell. It is also a picture you can see today: like many of the Italian Riviera towns, Spotorno is much as it was when Lawrence was there. The railway has been moved to the back of the town from the centre, and there are high-rise flats where the local quarry once was, but Spotorno retains its charming medieval centre, with the delicious smell of cooking from family-run trattorias, geraniums tumbling from window boxes and washing flapping from balconies. Some of the houses in its narrow alleys still have faded frescoes; those on the front of the parish church of the Santissima Annunziata, by contrast, have been recently restored to their original bright colours.

Lawrence was still nostalgic for New Mexico; in an essay written at Spotorno, ‘A Little Moonshine with Lemon’, he compared the view from the balcony of his bedroom on the top floor of the Villa Bernarda with that from the ranch at Kiowa which he had just left behind. He recalled with nostalgia the fir tree in front of the cabin at the ranch, and the horses he and Frieda rode there. But he also remembered how cold it was in winter, with snow on the ground.

In Spotorno there was no snow, and he was drinking vermouth to celebrate St Catherine’s Day (25 November) – the name day of Rina Secker. At Kiowa, by contrast, he would have been drinking moonshine, because of Prohibition – ‘not very good moonshine, but still warming: with hot water and lemon, and sugar, and a bit of cinnamon’. Just before moving into the villa, Lawrence had written a review of a book called The Origins of Prohibition, in which he celebrated the ‘healthy’ human appetite for beer and wine and condemned the hypocrisy of those who banned alcohol for others while allowing themselves ‘the occasional drink’.

In a second essay, ‘Europe v. America’, he now spelt out his ‘relief’ at being back in Europe. The view from his balcony, he wrote in a poem entitled ‘Mediterranean in January’, ‘persuades me to stay’. He would not go back to New York, the city of bank clerks, until the Mediterranean turned ‘shoddy and dead’ and the sun ‘ceases shining overhead’. The contrast with America, in other words, was in Europe’s – and Italy’s – favour. ‘The sea goes in and out its bays, and glitters very bright’ he wrote. ‘There is something forever cheerful and happy about the Mediterranean: I feel at home beside it’. In Etruscan Places he would observe that it was ‘a relief to be by the Mediterranean, and gradually let the tight coils inside oneself come slack’. He preferred the ‘deep insouciance’ of Italy to the ‘frenzy’ which was ‘characteristic of our civilisation but which is at its worst, or at least its intensest, in America.’ Italy felt ‘very familiar’, Lawrence told his American friends on Capri, Earl and Achsah Brewster, ‘almost too familiar, like the ghost of one’s own self. But I am very glad to be by the Mediterranean again for a while. It seems so versatile and so young, after America, which is everywhere tense. I wish we were all richer, and could loiter around the coasts of the old world, Dalmatia, Isles of Greece, Constantinople, Egypt. But it’s no good: we’ve got to go piano-piano’.

‘Almost too familiar’: the phrase will strike a chord with anyone who has become involved with Italy and cannot escape its seductive spell – and Lawrence was very involved indeed, to the point where he was nicknamed ‘Lorenzo’. His decision to accept Rina and Martin’s advice and go to Spotorno did not exactly come out of the blue. Although he is more often associated with the Midlands and New Mexico, he had a life-long passionate attachment to Italy, starting in 1912, when as a young man he fell in love with Frieda Weekley, the aristocratic German wife of a Nottingham professor.

BORN BARONESS Emma Maria Frieda Johanna von Richthofen at Metz, one of three von Richthofen sisters, she was a force of nature, distantly related to Manfred von Richthofen, the First World War fighter pilot known as the Red Baron. Her father, also a Baron, was governor of Metz: her mother too was an aristocrat by birth. Lawrence found Frieda – at 32, six years older than himself – uninhibited, direct and sensual, the ‘woman of a lifetime’.

Frieda had a comfortable domestic life with Professor Weekley – but had secretly already had a series of lovers, both in Nottingham and on trips back to her native Germany when her husband thought she was visiting relatives. She was pretty and voluptuous: only later did she fill out into the large, dumpy and rather unkempt woman she became, making it more difficult to imagine her as a Teutonic temptress.

Frieda certainly believed in her right to free love. She believed too that it was the role of a woman to nurture a man’s talent or genius: one of her lovers was Otto Gross, the psychiatrist, whom she admired as ‘a remarkable disciple of Freud’; another was Ernst Frick, a painter and anarchist. Frieda’s choice of Weekley as a husband might therefore seem out of character. On the other hand, although conventional (certainly compared to Gross or Frick), he was no dry, dusty professor. Author of The Romance of Words, Ernest Weekley was good-looking, witty, even passionate. He taught modern languages at Nottingham, and spent a year as a lecturer at the University of Freiburg – and when he met Frieda and proposed to her in the Black Forest, she accepted. They were married in 1899.

But Weekley was 34 at the time of their marriage, and Frieda was 20. Although she had three children in swift succession – Montague (1900), known as Monty, Elsa (1902) and Barbara (1904), known as Barby, who would later play a key role in the drama at Spotorno – Frieda began to feel trapped. She was lively and mischievous, while the professor was more reserved, and their sex life was, by her own account, less than satisfactory. As she puts it in her memoir Not I, But the Wind (the title is taken from a DH Lawrence poem), ‘I was living like a somnambulist in a conventional set life’.

The young man who woke her from her sleep was from a very different background. David Herbert Lawrence, known to his friends as Bert, was the fourth of five children of Arthur Lawrence, a miner, and his wife Lydia, who lived in the coalmining district of Eastwood in Nottinghamshire. Arthur had been a handsome man and an accomplished dancer, a gregarious figure and a ‘lively talker’ with blue eyes and a curly black beard – but he drank too much, and Lydia came to feel she had married beneath her. Their often violent rows are reproduced in Paul Morel– later re-named Sons and Lovers– together with Lawrence’s close, intense relationship with his possessive mother and the trauma of her death from cancer in 1910.

Lawrence was a frail youth, subject to bouts of pneumonia. He attended the local Congregational Chapel, won a scholarship to Nottingham High School and – after a short period as a clerk in a surgical appliances factory – studied for a teacher’s certificate at what was then University College, Nottingham, teaching first in Nottingham itself and then in Croydon. But he knew he was destined for something more: he once startled his boyhood friend Willie Hopkin by declaring he was going to be an author, adding ‘I have genius! I know I have.’

Ford Madox Ford later recalled that all his life, Lawrence ‘considered that he had a “mission”.’ He began to write stories and poems, drafting a novel which would become The White Peacock, published in 1910. With his pale face, lean, lanky figure, excitable high-pitched Midlands-accented voice and penetrating blue eyes (the red beard came later), he already had what Katherine Mansfield would later call a ‘passionate eagerness for life’. He was delicate and sensitive, and given to sudden rages, his Nottingham friends later recalled, but also capable of impetuous acts of kindness and generosity.

His first love, Jessie Chambers, lived at Haggs Farm in the countryside near Eastwood, where Lawrence spent much of his spare time. Some of his love affairs were sexual, some platonic. Although Jessie shared his love of literature and was the model for Miriam in Sons and Lovers, her apparently frigid and ‘sacrificial’ reaction when he finally persuaded her to have sex with him led to their breakup. Other women in his life in the early days included Alice Dax, a married woman, and Louie Burrows, a fellow student teacher who Lawrence described as ‘a glorious girl … bright and vital as a pitcher of wine’ and to whom he was engaged for just over a year (though he later said he had not really meant to propose to her).

By the time he went to the Weekleys’ house for lunch at his former professor’s invitation early in March 1912, Lawrence was making his way in the world. Nothing, however, prepared him for Frieda. That fateful encounter in the sitting room in the middle class suburb of Mapperley would change his life – and hers. Lawrence had gone to seek Weekley’s advice about his idea of going to Germany to teach. But the professor was not there at first, and so Lawrence and Frieda had a fateful half hour alone together, talking about Oedipus and the dichotomy in women between ‘body and spirit’. Many years later Frieda recalled ‘the red velvet curtains blowing out of the French windows’ as they talked, and Lawrence’s long, thin figure and ‘quick straight legs, light, sure movements. He seemed so obviously simple. Yet he arrested my attention. There was something more than met the eye’. Lawrence reported excitedly to the literary critic and editor Edward Garnett that Frieda was ‘splendid’, ‘the finest woman I’ve ever met’.

Frieda, it seems, at first just wanted an affair – she and Lawrence crossed the Channel together and travelled to Metz in May 1912. But before leaving for Germany she had confessed to her husband about her affairs with Gross and Frick, and Lawrence was the last straw. Weekley sent a telegram to Frieda to say their marriage was at an end, with no possibility either of reconciliation or of access to the children. Frieda was to suffer terribly from being deprived of her son and daughters, yet later claimed she had been determined to marry Lawrence from the first, writing that ‘I had to be his wife if the skies fell, and they nearly did.’

And so Lawrence and Frieda began a union which lasted until Lawrence’s death 18 years later – beginning it in earnest not in Germany, but in Italy. However, it was a union in which Frieda continued to believe in ‘free love’, while Lawrence hankered after a solid marriage and a family, though he and Frieda never did have children. ‘The best thing I have known’, he wrote much later in Fantasia of the Unconscious, ‘is the stillness of accomplished marriage, when one possesses one’s own soul in silence, side by side with the amiable spouse, and has left off craving and raving and being only half of one’s self.’ Frieda was not much of a Hausfrau; on the contrary, she was careless and slovenly, and it was the tidier Lawrence who throughout their life together did all the housework, cleaning, cooking and maintenance. They quarrelled incessantly. But he saw her always as the Frieda he had fallen for in Nottingham.

They stayed at first at an inn in the Isar Valley, then at a flat in Icking made available to them by Frieda’s married sister Else, who used it as her own ‘love nest’ for affairs. Frieda made clear to Lawrence from the start that she too was still a free spirit by going to bed with a German army officer in Metz, and then by swimming across the chilly Isar River at Icking and offering herself to a no doubt startled woodcutter (shades of Mellors the gamekeeper). As they made their way over the mountains toward the Italian border in August 1912 with knapsacks and just £23 in cash, she made love to Harold Hobson, a student who had joined them on the trek together with Garnett’s son David, while Lawrence was out picking Alpine flowers. According to Lawrence’s autobiographical novel Mr Noon, Frieda told Lawrence bluntly that Hobson ‘had me in the hay hut’, her motive being that ‘he told me he wanted me so badly’.

Averaging ten miles a day, they trudged over the mountains in the rain, past the roadside crucifixes which gave Lawrence the subject for his essay ‘The Crucifix Across the Mountains’, which begins ‘The imperial road to Italy goes from Munich across the Tyrol, through Innsbruck and Bozen to Verona, over the mountains.’ He saw the crucifixes and statues of Christ as beautiful monuments to an ‘obsession with the fact of physical pain, accident, and sudden death.’

Lawrence’s mood darkened further when he misread the map and he and Frieda became hopelessly lost. Somehow they got by train to Bolzano (then still in Austria and called Bozen), but were turned away when they tried to get a room because of their filthy appearance. They did find a room in Trent, but it was infested with bugs and the toilets were ‘indescribable’. With Frieda in floods of tears, they took a train to Riva on Lake Garda, largely because a station travel poster had caught their eye, portraying what they hoped would turn out to be the Italy they had dreamed of: a purple and emerald green lake lined with roses, oleanders and vineyards full of black grapes.

It was. At Riva, just (at that time) on the Austrian side of the border, but thoroughly Italian in character, they stayed in a pensione, the Villa Leonardi. They were so poor they had to cook in their room (to the annoyance of the maid). But Lawrence was ecstatic. It was ‘quite beautiful, and perfectly Italian’, he wrote to Edward Garnett. ‘The water of the lake is of the most beautiful dark blue colour you can imagine’ and ‘wonderful to swim in’. ‘Out here seems so much freer than England,’ he wrote to his former fiancée in Nottingham, Louie Burrows. ‘The lake is dark blue, a beautiful colour, and so sunny. Here we have only had one shower in a fortnight. It is beautiful weather, and warm.’ The figs were ‘just ripe – 2d a lb – and grapes – miles and miles of vineyards – and peaches. They are also just getting the maize. It’s fearfully nice.’

2

Gargnano to Lerici

LAWRENCE’S LOVE AFFAIR with Italy now began. Everything was ‘beautiful’. ‘I am here on the border of Italy,’ Lawrence wrote to his former married lover in Nottingham, Alice Dax, from Riva in September 1912. ‘It is a beautiful place. Figs and peaches and grapes are just ripe. Grapes are hanging everywhere, tons of them, very beautiful.’ The lake was dark blue and ‘clear as crystal. It is very beautiful indeed.’ He and Frieda were planning to spend the winter at Gargnano, 20 miles further down the lake, in Italy proper. Gargnano, Lawrence told Louie Burrows, was ‘a funny place, rather decayed’, but ‘fearfully pretty, backed with olive woods and lemon gardens and vineyards. I think I shall be happy there, and do some good work.’

At Gargnano, noted for its red wines and home to a detachment of the Bersaglieri regiment with their elaborate uniforms and plumed helmets, Lawrence and Frieda took rooms on the first floor of the Villa Igea overlooking the lake. The Bersaglieri were – and still are – famed for running in formation instead of marching. As the historian GM Trevelyan wrote in 1919, they were ‘the noblest Italian types’. Watching them from her window, Frieda wrote to David Garnett, ‘They are beautiful creatures. The men so loose and soldiers with such hats, a foam of cockfeathers on them I long for one, a hat not a soldier.’ Some 13 years later she did long for the soldier as much as the hat, in the form of Angelo Ravagli, the Bersaglieri officer who was their landlord in Spotorno. In 1912 Lawrence too was struck by the Bersaglieri, telling Edward Garnett in October that the soldiers were ‘so good looking and animal’ – not, of course, anticipating that one such good-looking animal would become his wife’s lover.

The garden of the Villa Igea – situated in a lakeside continuation of Gargnano called, rather confusingly, Villa – had roses, oranges and persimmons, which Lawrence was much taken with: at Spot-orno 13 years lat...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Postscript

- Dramatis Personae

- A Note on Sources

- Endnotes

- Bibliography