![]()

Chapter One

From Blériot to Prévost at Monaco

‘The collective identity of the aeroplane as revealed at Reims showed the world’s new vehicle as capable of conveying two men through the air in comparative safety at some 40 mph.’

Charles Gibbs-Smith writing in Aviation magazine.

In 1909 the aeroplane came of age in a year marked by Louis Blériot’s successful Channel crossing in July and a month later during the first great air meeting on the Betheny Plain outside Reims: La Grande Semaine d’Aviation de la Champagne. The meeting at Reims reinforced the message of Blériot’s Channel crossing by bringing together the finest pilots and machines and showing the variety and possibilities of the new air vehicle to governments and public alike. Local French vintners and city officials founded the Reims Air Meet when they agreed to raise prize money and sponsor the air show and because of Blériot’s feat the previous month, the organizers of the Reims Meet were expecting a large turnout at their event. To accommodate the anticipated crowds, they transformed Betheny into a massive aerodrome and a mini-city, building barber and beauty shops, telephone and telegraph offices, and a huge grandstand, complete with a 600-seat restaurant that overlooked the airfield. To keep people entertained between flights, they hired stilt-walkers and tightrope artists to perform.

Louis Blériot was the first pilot to fly across the English Channel in his heavier-than-air Blériot XI monoplane on 25 July 1909, landing heavily at Northfall Meadow, Dover. The Blériot Memorial marks the spot where he landed.

Hubert Latham’s Antoinette IV at Reims.

Twenty-two aviators came to Reims to compete. All of them, save two, were Frenchmen. Some of the better-known French pilots included Blériot, Hubert Latham, Henri Farman and Eugène Lefebvre, while George Cockburn, a Scot, and Glenn Curtiss, an American, were the only foreign competitors. Although most of the pilots were experienced, there were also a few who were not. One was Emile Ruchonnet, a Swiss engineer who worked at the time for the Antoinette Company in building the Antoinette aeroplanes flown by Latham and his cousin, René Labouchère. Ruchonnet had flown his first aeroplane only two days before the meet and was tragically killed in January 1912 when his machine crashed at Senlis in France.

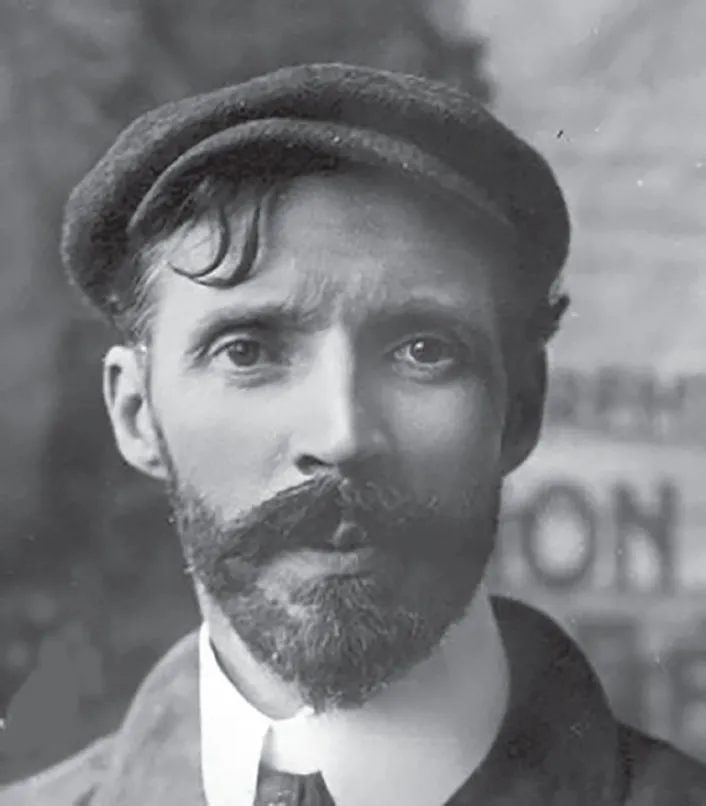

Eugène Lefebvre at Reims sitting in a Wright biplane. He was killed later in the year at Juvisy-sur-Orge and is considered to be the first victim of an air crash.

The Gordon Bennett Cup Race, or speed contest as it was commonly known, was the most important event of the Reims Air Meet and the race that everyone wanted to watch. Pilots had to fly two circuit laps consisting of 6 miles with each team allowed three entrants. Despite its comparatively meagre prize money, most spectators considered it the premier event of the week. American James Gordon Bennett, the famous publisher of the New York Herald newspaper and a long-time fan and sponsor of various speed contests, lent his name to the race by putting up the prize money and offering a trophy. Blériot, Europe’s most celebrated aviator, was favoured to win, but as Glenn Curtiss, the lone American and a celebrated pilot in his own right made clear, the Frenchman was going to have to fight if he wanted to win the race.

Glenn Curtiss at the controls of what is thought to be the Reims Racer. At Reims he was one of only two foreign competitors along with George Cockburn.

By Saturday, 28 August, the day of the speed race, the field of competitors had narrowed considerably due to several crashes. At one point during the week, there had been at least a dozen disabled or wrecked planes on the field. Curtiss, fearing just such a disaster, had refused to enter his aeroplane, called the Reims Racer, in any other contests besides the Gordon Bennett Cup. All told, because of the high attrition rate, only five pilots stood ready to race for the cup: Curtiss, Blériot, Latham, Lefebvre and Cockburn. Curtiss was the first to fly the two laps around the course, averaging 46.5 mph and establishing the benchmark time of fifteen minutes and fifty seconds. Then Latham, Lefebvre and Cockburn each tried to beat his mark, but failed in the attempt; it was now up to Blériot, the last person to fly. On his first lap, Blériot led Curtiss by four seconds and was averaging 47.75 mph, but on his second lap he slowed considerably and when he crossed the finish line, Curtiss had won the race by six seconds. At first the French crowd was stunned by Blériot’s performance, but after the initial shock they eventually started cheering for Curtiss and proclaimed him the new ‘Champion Aviator of the World’. That evening also saw Henri Farman flying his Farman III and Eugène Lefebvre in his Wright Type A contesting the Prix de Passengers, the passenger-carrying competition. Both pilots successfully managed to take off with one passenger, but Farman won by taking off a second time with two passengers and completing a circuit. Sadly, Lefebvre was killed in an air accident at Juvisy-sur-Orge in September 1909, only nine days after the end of the Reims event.

Probably the first aerobatic pilot was Eugene Lefebvre who thrilled the crowds at Reims. Lefebvre had only learned to fly that summer.

Léon Delagrange about to land in a Blériot XI at Reims. Note the number of spectators present.

Between 300,000 and 500,000 spectators witnessed the races and contests during the week. Of the thirty-eight aircraft originally registered to compete, only twenty- three took to the air and, of those, fifteen were biplanes and eight were monoplanes. In all, the pilots completed eighty-seven flights during the competition. For most of the people who attended the event, the Reims Air Meet showed that aviation competitions were a tremendously exciting form of entertainment and as one spectator, David Lloyd George, a future British prime minister noted, the meet also proved that ‘flying machines are no longer toys and dreams...they are an established fact.’ For those who had any doubts about the future of aviation, the Reims Air Meeting not only legitimized the importance and significance of flight, but also set the standard by which people would measure all future air meets.

Although the first flight in Germany was made by the Danish inventor Jacob Ellehammer on 28 June 1908, it was nearly two years later that Hans Grade won the 40,000 Reichmark prize for the first figure of eight to be flown in an all-German machine. A month later in November 1909, the Austrian Igo Etrich made the first successful flights in his monoplane at Weiner-Neustadt, a design that eventually evolved into the successful Taube in 1910 which was first produced by Rumpler. In June and July 1911 the Circuit of Germany began at Johannisthal airfield near Berlin with seventeen stages ending in Berlin. The pilots completed one stage each day, although they had more than one day’s stay at some stage locations to compete in flight competitions, such as the Kiel flight meeting. The stage winner was the one who had flown through the route fastest; the overall winner was the pilot who had flown the most kilometres at the end of the advertised total route. First place went to Benno König flying an Albatros-Farman, Hans Vollmöller came second and Bruno Büchner third. On 19 June, Hellmuth Hirth also set a new altitude record during a flight from Kiel at 7,217ft and later in 1911 he won the Munich to Berlin Race in a Rumpler-Taube. Flight in Germany had come of age but there was always a cost: Benno König died of injuries sustained in an air accident on 1 July 1912.

Hans Grade seated in the Grade monoplane after winning the 40,000 Reichmark prize for the first figure of eight to be flown in an all-German machine.

A replica Rumpler-Taube built by Art Williams which can be seen at the Museum of Flight in Seattle.

Three years before the Reims Meet, the Daily Mail had offered a prize of £10,000 to the first pilot to fly from London to Manchester within twenty-four hours. Only two landings were allowed and the aircraft had to start and finish the flight within 5 miles of the London and Manchester offices. At the time the prize was offered, the newspaper’s money appeared to be quite safe and was believed to be unwinnable, prompting Punch magazine to offer a similar sum for the first man to swim the Atlantic Ocean!

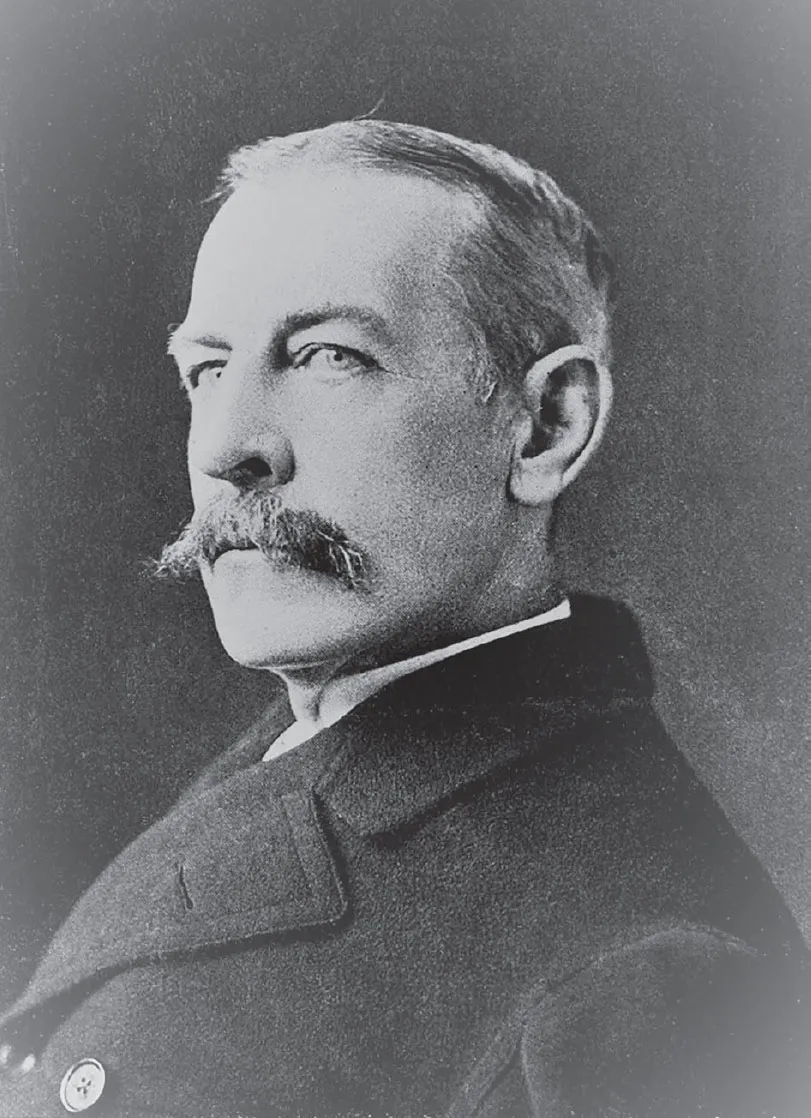

Benno König, pictured on the right, won the Deutsche Rundflug in 1911 flying an Albatros-Farman biplane.

However, by 1910 the extraordinary pace of aerial development meant that a flight between London and Manchester was now possible. Present at the Reims meeting was a 30-year-old Englishman called Claude Grahame-White who was running a successful car dealership in Mayfair. Less than a year before he had scarcely bothered with aviation, but then Blériot flew across the Channel and at once Grahame-White was interested. A month later he met Blériot, and in a sudden burst of enthusiasm agreed to buy one of the famous Frenchman’s latest machines. He was apparently told by Blériot that he had designed a newer and faster machine than that which had flown the Channel. It was a two-seater monoplane, powered by a 50hp Gnome rotary engine and it was entered for the Rheims Air Meet. Grahame-White said he would buy the machine at the close of the meeting. Like many other machines, the Blériot XII never saw the end of the display. It caught fire in the air and nearly burned its creator and pilot to death. In those days, however, a crash, no matter how serious, was looked upon as part of the business and in no way deterred aviators or enthusiasts.

Blériot was flying again within a few days, and Grahame-White was as keen as ever to acquire one of his machines. The monoplane was finished in November 1909, and Grahame-White immediately learned to fly it. After only half an hour’s ground instruction Grahame-White flew his first solo flight. From that point in time events progressed at a startling pace.

Grahame-White’s announcement that he intended to compete for and win the London to Manchester prize came as a complete surprise. He had heard that Louis Paulhan was also to compete and was determined to anticipate the French pilot in his quest for the prize. Given that his Blériot monoplane would not stand up to the rigorous demands of the race, Grahame- White bought a Farman III complete with the new 50hp Gnome rotary engine.

Henri Farman made several record-breaking flights, including one of 112 miles in three hours and another of just over 144 miles in four hours, seventeen minutes.

Henri Farman was an Anglo-French aviator and aircraft designer who was making a name for himself and his brother, Maurice Farman....