- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

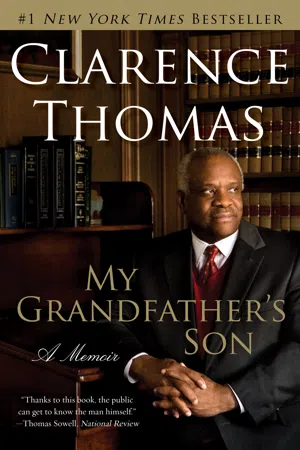

Provocative, inspiring, and unflinchingly honest, My Grandfather's Son is the story of one of America's most remarkable and controversial leaders, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, told in his own words.

Thomas speaks out, revealing the pieces of his life he holds dear, detailing the suffering and injustices he has overcome, including the polarizing Senate hearing involving a former aide, Anita Hill, and the depression and despair it created in his own life and the lives of those closest to him. In this candid and deeply moving memoir, a quintessential American tale of hardship and grit, Clarence Thomas recounts his astonishing journey for the first time.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Sun to Sun

I was nine years old when I met my father. His name was M. C. Thomas, and my birth certificate describes him as a “laborer.” My mother divorced him in 1950 and he moved north to Philadelphia, leaving his family behind in Pinpoint, the tiny Georgia community where I was born. I saw him only twice when I was young. The first time was when my mother called her parents, with whom my brother Myers and I then lived, and told them that someone at her place wanted to see us. They called a cab and sent us to her housing-project apartment, where my father was waiting. “I am your daddy,” he told us in a firm, shameless voice that carried no hint of remorse for his inexplicable absence from our lives. He said nothing about loving or missing us, and we didn’t say much in return—it was as though we were meeting a total stranger—but he treated us politely enough, and even promised to send us a pair of Elgin watches with flexible bands, which were popular at the time. Though we watched the mail every day, the watches never came, and when a year or so had gone by, my grandparents bought them for us instead. My father had broken the only promise he ever made to us. After that we heard nothing more from him, not even a Christmas or birthday card. For years my brother and I would ask ourselves how a man could show no interest in his own children. I still wonder.

I saw him for the second time after I graduated from high school. He had come to see his own father in Montgomery, not far from Pinpoint, and I went there to visit him. I felt I owed it to him—he was, after all, my father, and he had let my grandparents raise me without interference—but Myers would have nothing to do with “C,” as we called him, saying that the only father we had was our grandfather. That may sound harsh, but it was nothing more than the truth, for me as much as my brother. In every way that counts, I am my grandfather’s son. I even called him Daddy because that was what my mother called him. (His friends called him Mike.) He was dark, strong, proud, and determined to mold me in his image. For a time I rejected what he taught me, but even then I still yearned for his approval. He was the one hero in my life. What I am is what he made me.

I am descended from the West African slaves who lived on the barrier islands and in the low country of Georgia, South Carolina, and coastal northern Florida. In Georgia my people were called Geechees; in South Carolina, Gullahs. They were isolated from the rest of the population, black and white alike, and so maintained their distinctive dialect and culture well into the twentieth century. What little remains of Geechee life is now celebrated by scholars of black folklore, but when I was a boy, “Geechee” was a derogatory term for Georgians who had profoundly Negroid features and spoke with a foreign-sounding accent similar to the dialects heard on certain Caribbean islands.

Much of my family tree is lost to me, its secrets having gone to the grave with my grandparents, but I know that Daddy’s people worked on a three-thousand-acre rice plantation in Liberty County, just south of Savannah, and after their manumission they stayed nearby. The maternal side of my mother’s family also came from Liberty County, and probably worked on the same plantation, most of which has remained intact. Not long ago I saw it for the first time—during my youth blacks never went there unless they had a good reason—and found that the old barn in which my great-great-grandparents surely labored a century and a half ago is now a bed-and-breakfast inn whose Web site calls it “a perfect honeymoon hideaway.” You’d never guess that slaves once worked there.

My mother, Leola, whom I called Pigeon, her family nickname, was born out of wedlock in 1929 or 1930.* Her mother died in childbirth, and she saw little of Daddy as a child. At first she was raised by her maternal grandmother, who died when she was eight or nine years old. Then she went to live in Pinpoint with Annie Green, her mother’s sister. C and his family moved near there to work at Bethesda Home for Boys, which is next to Pinpoint; that was where he met Pigeon, all of whose children he sired. My sister, Emma Mae, was born in 1946, with Myers Lee following three years later. I was born between them in Sister Annie’s house on June 23, 1948. I was delivered by Lula Kemp, a midwife who came from the nearby community of Sandfly. It was one of those sweltering Georgia nights when the air is so wet that you can barely draw breath. To this day my mother swears I was too stubborn to cry.

Pinpoint is a heavily wooded twenty-five-acre peninsula on Shipyard Creek, a tidal salt creek ten miles southeast of Savannah. A shady, quiet enclave full of pines, palms, live oaks, and low-hanging Spanish moss, it feels cut off from the rest of the world, and it was even more isolated in the fifties than it is today. Then as now, Pinpoint was too small to be properly called a town. No more than a hundred people lived there, most of whom were related to me in one way or another. Their lives were a daily struggle for the barest of essentials: food, clothing, and shelter. Doctors were few and far between, so when you got sick, you stayed that way, and often you died of it. The house in which I was born was a shanty with no bathroom and no electricity except for a single light in the living room. Kerosene lamps lit the rest of the house. In the wintertime we plugged up the cracks and holes in the walls with old newspapers. Water came from a nearby faucet, and we carried it through the woods in old lard buckets. They were small enough for us to fill up and tote home, where we poured the contents into the washtub or the larger kitchen buckets, out of which we drank with a dipper. We also kept a barrel at the corner of the roof to catch the rainwater in which our clothes were washed. We scrubbed them on a washboard set into the tub at an angle, rinsed them twice, wrung them by hand, and hung them out to dry.

Pinpoint was at the water’s edge, and just about everyone I knew did some kind of water-related work. Many of the men raked oysters during the winter and caught crabs and fish in the spring and summer. Their boats, which we called “bateaus,” could be heard far away in the marshes, straining to carry home their heavy loads. They would slowly emerge from the labyrinth of surrounding creeks and pull up to the dock, where the day’s haul was unloaded. The crabs went to the crab house to be cooked, while the oysters were tossed into a bin at the oyster factory next door. Every winter the women of Pinpoint shucked oysters in the factory, a cold, damp cinderblock building whose cement floor was always wet from constant washing. (The empty building still stands by the creek, which is now clogged with weeds.) Three woodstoves stationed like sentries in the center of the room provided the only heat, and the air was heavy with the smells of burning wood, oysters, and the salt and mud of the nearby creek. The women cracked the shells and pulled out the oysters with deft, practiced movements, talking and singing spirituals as they worked. In the summer they picked crabs emptied from large baskets onto a table. The women who didn’t work there served as domestics in the homes of white people, bringing back such dubious treats as the crusts of the slices of bread that had been used to make the hors d’oeuvres served at their employers’ parties. When they weren’t busy fishing, most of the men made extra money by doing construction, gardening, knitting fishing nets, and other odd jobs on the side.

Life in Pinpoint was uncomplicated and unforgiving, but to me it was idyllic. Myers and I skipped oyster shells on the water with our cousins and caught minnows in the creeks. We rolled old automobile tires and bicycle rims along the sandy roads, sure that there could be no better fun. We had only two store-bought toys, a beat-up old red wagon and a little fire truck that I could pedal. Instead we played with “trains” made out of empty juice cans strung together with old coat hangers and weighted with sand, and we also made gunlike toys called “pluffers” out of canes and wooden mop or broom handles, using green chinaberries as ammunition. We were supposed to stick close to home, but no sooner did the adults leave for work each day than we ran for the sandy marshes, in which we hunted for fiddler crabs. We wandered through the nearby woods, sometimes tussling with the white kids from Bethesda Home for Boys, the oldest orphanage in America, an oasis of big brick buildings and expansive, well-kept lawns. Any attempt to invade this paradise was fiercely resisted by the lucky boys who lived there.

Nothing about my childhood seemed unusual to me at the time. I had no idea that any other life was possible, at least for me. Sometimes I heard the grown-ups talk about the white people for whom they worked, but I took it for granted that they were all rich. Photographs in newspapers and magazines gave me fleeting glimpses of an unreal existence far from home, but Pinpoint was my world, and until I started going to school, the only sign that there might be another one was the occasional airplane or blimp I saw flying overhead.

I entered Haven Home School, the local grammar school for blacks, in the fall of 1954. I walked with my sister and the older kids to the end of Pinpoint Road to wait for the school bus, and I could barely contain my excitement when it came rolling around the bend at last. That was the year when Myers and Little Richard, our cousin, burned down Sister Annie’s ramshackle house, in which we still lived, while playing with the matches used to light the stove and lamps. As I came home from the school bus, I saw that the house had become a smoldering pile of ashes and twisted tin. After that, Pigeon took my brother and me to Savannah, where she was keeping house for a man who drove a potato-chip delivery truck. We moved into her one-room apartment on the second floor of a tenement on the west side of town. Emma Mae stayed with Annie, who went to live with one of our cousins until she could build another house.

Nowadays most people know Savannah from reading Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. To them it is an architectural wonderland full of well-heeled eccentrics and beautifully preserved eighteenth-and nineteenth-century houses. I didn’t live in that part of town. When I was a boy, Savannah was hell. Overnight I moved from the comparative safety and cleanliness of rural poverty to the foulest kind of urban squalor. The only running water in our building was downstairs in the kitchen, where several layers of old linoleum were all that separated us from the ground. The toilet was outdoors in the muddy backyard. The metal bowl was cracked and rusty and the wooden seat was rotten. I’ll never forget the sickening stench of the raw sewage that seeped and sometimes poured from the broken sewer line. Pigeon preferred to use a chamber pot, and one of my Saturday-morning chores was to take it outside and empty it into the toilet. One day I tripped and tumbled all the way down the stairs, landing in a heap at the bottom. The brimming pot followed, drenching me in stale urine.

Pigeon enrolled me in the afternoon first-grade class at Florance Street School, one of the first public schools in Savannah built specifically for black students. Myers wasn’t old enough to go, so she made other arrangements for him. I don’t know where he went, but she took him with her early each morning, leaving me to fend for myself until it was time for me to walk to school. Breakfast, when I had it, was usually cornflakes moistened with a mixture of water and sweetened condensed milk. (We couldn’t afford sugar.) Pigeon always came home tired and drained. It was as though her job sapped all the hope out of her. She worked to stay alive and keep us alive, nothing more.

Many of the kids I had known at Haven Home School were relatives of one sort or another, but now I was alone, a stranger in an ugly, unfamiliar world. My lessons were slow moving and repetitive, so I started skipping school and wandering around the west side of town, mystified and curious. In the evenings and on rainy days, I would spend hours sitting by our solitary second-story window, watching the parade of people walking up and down the dirt street that ran past our building. Men gathered around open fires, talking as they warmed themselves. Sometimes shrill-sounding sirens pierced the night. Their wail might mean an arrest, an accident, or a fire, all of them welcome breaks in the bleak monotony of my new life.

It didn’t help that our apartment was so uncomfortable. My mother and brother shared the only bed, leaving me to sleep on a chair. It was too small, even for a six-year-old. We couldn’t afford to light the kerosene stove very often, so I was cold most of the time, cold and hungry. Though there was only one store in Pinpoint, the rivers and the land had provided us with a lavish and steady supply of fresh food: fish, shrimp, crab, conch, oysters, turtles, chitterlings, pig’s feet, ham hocks, and plenty of fresh vegetables. Never before had I known the nagging, chronic hunger that plagued me in Savannah. Hunger without the prospect of eating and cold without the prospect of warmth—that’s how I remember the winter of 1955.

Late that summer we moved to a two-bedroom apartment on East Henry Lane. Our new neighborhood was just as poor, but a better place to live. We had a kitchen with a stove and refrigerator. The outdoor toilet didn’t leak. The beds were old, but at least I had one of my own, and it was big enough for a growing boy. My mother’s father lived nearby on East Thirty-second Street, and we visited him and our grandmother several times that summer. Their house, which had been built three years earlier out of cinder blocks, was painted a gleaming white. It had hardwood floors, handsome furniture, and an indoor bathroom, and we knew better than to touch anything.

One Saturday morning in August, Pigeon told Myers and me that we were going to live with our grandparents. Without a word of explanation, she dumped our belongings into two grocery bags and sent us out the front door. We walked straight to our grandparents’ house, passing by the places that were to become the landmarks of our childhood: Mr. Lee’s grocery store, Mr. Goodman’s grocery store on the opposite corner, Mr. Moon’s fish market, Reverend Bailey’s shoe store, the Polar Bear Ice and Coal Company, and the Meddin Brothers meat-packing company. It was only two and a half blocks from East Henry Lane to the spotless white house on East Thirty-Second Street, but in all my life I’ve never made a longer journey.

I don’t know the whole story of Pigeon’s decision to send Myers and me to live with our grandparents. The main reason, though, must have been that she simply couldn’t take care of two energetic young boys while holding down a full-time job that paid only ten dollars a week. C did nothing—and I mean nothing—to help us. A court had ordered him to pay child support to Pigeon, but he ignored it. Since she refused to go on welfare, she needed some kind of help, and I suspect my grandfather told her that we would either live with him permanently or not at all. He didn’t like complicated arrangements, and he may also have feared that giving us up after a short time would be too hard for him to bear. He often told us about a dog he had once owned that had strayed from the yard and was run over by a car. My grandfather was so devastated by the dog’s death that he never owned another one after that.

My grandparents were in their forties when they took us in, and had been married for more than two decades without having any children together. (Daddy had had two children out of wedlock before he married my grandmother, the second of whom was Pigeon, and my grandmother bore an illegitimate child of her own who died in infancy.) Perhaps they hoped that Myers and I might fill the empty place in their home and their hearts.

MY GRANDMOTHER’S NAME was Christine, but we always called her Aunt Tina (pronounced “Teenie”), as our cousins did, and she never asked us to call her anything else. Aunt Tina was a slight woman, five foot two and thin, with perfect teeth. She was soft spoken and easygoing, and I thought she was beautiful. Her favorite book was To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee’s novel about a black man falsely accused of raping a white woman. She must have bought it on one of her train trips to visit her sister, who lived in the Bronx. I doubt she ever read it all the way through—she had only a sixth-grade education—but she knew the story well, and in 1962 she took Myers and me to see the movie version. Aunt Tina must have been shocked to see that all our possessions fit into one grocery bag apiece, but she never said so. She showed us to our bright, airy new room, which contained matching twin beds with frilly white bedspreads, a chest of drawers, and a closet of our very own, and told us we were home now. From then on she did all she could to make that home warm and loving.

Myers Anderson, my grandfather, stood five foot eleven and weighed 195 pounds. He had proud West African features—high cheekbones, a broad nose, and very dark skin—and a thin mustache that he trimmed each morning with a Gillette razor. Daddy had only nine fingers, having lost his right index finger working on a boat. His hard, wiry body was strongly muscled, his deep bass voice intimidating. He had only a third-grade education, which he said amounted to nine months of actual learning since he went to school for only three months a year. It would be too generous to call him semiliterate; his pride made him blame his reading difficulties on bad eyesight, but the truth was that he could barely read at all. By the time I was in third grade, I was the best reader in the house. As long as he lived, though, Daddy struggled mightily with the newspaper and the Bible, and once he mastered a passage of Scripture he would read it over and over again.

Daddy rarely spoke of his own father except to say that he’d been a “jackleg preacher,” meaning that he was self-taught. Perhaps he didn’t know much more than that, and preferred to keep what he did know to himself. I do know, however, that Daddy was illegitimate, and that he resented his father’s lack of interest in him. He believed that he had been born in Savannah in 1907, and later on he chose April 1 as his birthday, in the same way that so many other southern blacks picked out similar birthdays for themselves. (Louis Armstrong chose July 4, 1900.) His mother died when he was nine, and he went to live with his maternal grandmother, Annie Allen, in the Sunbury area of Liberty County. Annie died when Daddy was twelve, and he was turned over to her son and his wife, who lived nearby. Uncle Charles and Aunt Rosa already had thirteen children of their own, so he was just another mouth to feed. He often told us that he had spent his whole childhood being “handed from pillar to post.” Daddy always spoke of his grandmother, a freed slave, with reverence. A no-nonsense woman who didn’t spare the rod, she used to spit on the side of the road on a hot summer day and warn Daddy that he had better run his errand before the spittle dried if he wanted to escape a whipping; Uncle Charles beat him, too, sometimes with an oar, knocking him off his boat. Yet in spite of their harsh treatment—or because of it—Daddy knew they’d cared enough to raise him right, and he felt he owed them a debt of gratitude too great to repay. When Uncle Charles died in 1960, Daddy, Myers, and I knelt by the bed where his body lay and said the rosary.

In his youth Daddy worked on Uncle Charles’s boat, made bootleg liquor, and moved houses, among other things. Later on he bought an old truck and started cutting wood at night and s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. Sun to Sun

- 2. As Good as Us

- 3. The Corridor

- 4. No Room at the Top

- 5. The Golden Handcuffs

- 6. A Question of Will

- 7. “Son, Stand Up”

- 8. Approaching the Bench

- 9. Invitation to a Lynching

- 10. Going to Meet the Man

- Photo Section

- About the Author

- Praise for My Grandfather’s Son

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access My Grandfather's Son by Clarence Thomas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Law Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.