- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Charismatic Leadership in Islam

About this book

To understand Islam, one must understand the people who practice their faith. Consequently, this book is a detailed ethnographic study of two contemporary Sufi communities. It explores the perplexing range of theological and ritual variation, arguing for a direct correlation between Sufi multiformity and the agency of the spiritual leader, the Shaikh. He is principally responsible for shaping the community under his leadership

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Charismatic Leadership in Islam by Dejan Aždaji?,Dejan Aždajić in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Ministry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Exploring the Field

Introduction – Going to Them

I lived in the capital city of Sarajevo for six years before engaging in this research. During that time, I met diverse Sufi groups in the city and around the country, attending special events and increasing my cultural awareness. My personal Christian devotional practices and explicit commitment to belief in God were attractive to those that I encountered in the field, which helped me to establish closer relationships with them. I found that my Christian commitment did not diminish trust, or the responsiveness of the people with whom I interacted. Instead, I was treated with hospitality and kindness. Once it became clear that ‘my hobby’ would turn into an extensive research endeavour, I was pointed in the right direction to further my research.

My focus was in the city of Sarajevo where Sufism began in Bosnia and is home to the greatest number of Sufi communities in the country. I made the decision to investigate two communities, identified by the names of their respective leaders – Faruki and Hulusi. Although both belonged to the Naqshbandi Order, there were important differences. Faruki, an older Shaikh with fewer followers, appeared to represent a more traditional Sufi group, which was reflective of the way Sufism looked in Bosnia’s historical past. Hulusi, a younger Shaikh was more contemporary and had a large following. However, many similarities characterised these groups. Both met on a regular basis in a particular location and both were members of the same Sufi Order, striving toward moral perfection and the same spiritual goal of attaining proximity to God.

Entering Faruki’s World

Gaining access to Faruki’s community was not easy and depended upon meeting the old Shaikh and receiving his approval. This was challenging, because I did not know how to do this. I learned that the only place that he frequented regularly was a small calligraphy shop in Sarajevo owned by Hazim Numanagić, the grandson of one of Bosnia’s most famous Shaikhs, Husni Numanagić (1853-1931). Hazim was one of Faruki’s senior dervishes, or followers, and is one of the most renowned calligraphers in the country. During my research, Hazim became one of my most valuable links. Not knowing the exact time or day that Faruki would come, I decided to visit the shop over a number of days until our paths crossed, and when it did, Faruki gave me an opportunity to introduce myself and explain my research. After I was finished, he sat in absolute silence, taking slow puffs of his cigarette and staring at me with a penetrating gaze. The situation was quite uncomfortable but after looking at me for almost a minute he uttered, “Yes, I give you permission to come to us. I can see on your face that you are a good person. God sent you.” This simple verbal consent endorsed my long-term presence at the tekija (lodge), providing me with legitimacy in the eyes of the community members who welcomed me in their midst. Faruki’s approval also came with specific limitations, informing me that since I was not a Muslim, I was not allowed to participate in dhikr (the communal remembrance prayer ceremony) performances and prayer rituals.

Photo 1. Faruki and myself at the Calligraphy Studio

(taken with permission that it can be used in publications)

I began regularly attending Faruki’s weekly dhikr two or three times a week with about 30 participants, seated outside the circle as an observer and not a participant, but deliberately immersing myself in their sacred world. Since Friday meetings were based on discussion and less on religious performance, at these meetings I was a fully integrated member with the right to make comments and ask questions. These meetings helped me to acquire rich insights and focus on particular topics that I could introduce for further constructive comments.

Having received the blessing of the Shaikh, I was permitted to walk around at all times with a notebook in hand, and soon people stopped paying attention to this, although the value of keeping systematically written records became essential for later use.

One of the highlights of my time with Faruki was that he invited me twice to his home for dinner. This was seen as a great honour by community members, and increased their trust in me and their willingness to talk with me to such an extent that when I was unable to attend a meeting, some members felt that something was ‘missing’ in my absence.

The most pronounced and insurmountable obstacle was gaining access to female voices. Despite a number of attempts, I was only able to interview one woman. This was due to Faruki’s belief that women were not supposed to come to the tekija (lodge), but rather receive instruction and spiritual training from their husbands at home.

Bosnian Sufis have traditionally viewed the tekija or lodge, as an educational place for spiritual study. However, the word ‘tekija’ means more than a physical building. It represents an everyday lifestyle with strict discipline, spiritual practices and obedience to the Shaikh. Shaikh Faruki’s tekija is located on the outermost edge of the city of Sarajevo, away from the noise and excitement of the downtown area. Built in 2014 through private donations this ‘Sufi Centre’ is listed as a private residence providing the community with an independent status, separate from bureaucratic limitations and institutional oversight of the Islamic Community.

Photo 2. Shaikh Faruki’s Sufi Center

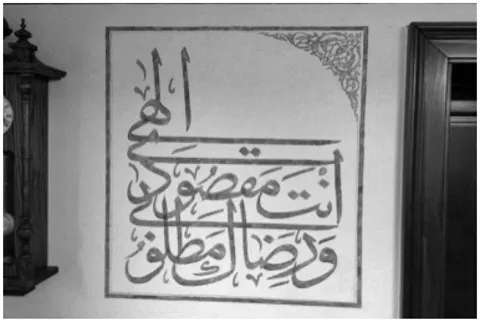

One of the most striking features of the tekija was its calligraphic beauty. Hazim was commissioned to decorate the entire interior of the tekija with verses from the Qur’an and other famous Sufi sayings in the hadith (quotations from Mohammed), all chosen by Faruki himself who was well versed in the Qur’an and able to quote large portions from memory. Conversations inside the tekija were held in a near whisper, and body movements were slow and discreet with a physical posture of humility, where members crossed their arms in front of the stomach while sitting or kneeling. Several minutes of silence might pass before conversations or instructions continued. Although most were kind and friendly, laughter was rare. The silence combined with the thick smoke from chain-smoking dervishes, created a contemplative ambience.

Photo 3. Beautiful Calligraphy in Faruki’s Tekija

Faruki’s tekija was secluded, surrounded by a large metal fence and eight-foot walls only open to the public during ritual performances on Thursdays, Fridays and Sundays. The same compound also housed Faruki’s residence where he, along with two of his adult children and grandchildren, all lived, as well as some of his followers and personal assistants. Next to the tekija was a small house that Faruki gave to a poor single mother and her three daughters, paying all their bills. This concern for the well-being of those without means was a characteristic of Shaikh Faruki.

Organisational Dimension

The organisational aspect of the tekija, its maintenance and finances were informal. I never heard a public announcement asking for financial or practical help. One time when coal was delivered, several dervishes, without asking, simply picked up a shovel and carried the coal where it needed to go.

The centrality of practising awareness of God’s involvement in all of life’s affairs and helping where necessary was an underlying theological principle reflecting the belief of Faruki and his followers that they were keeping the traditional Bosnian Naqshbandi way. Faruki explained that it was important to uphold tradition.

Faruki believed that he needed to wait for God to give him instruction as to who was meant to become a dervish, and this reluctance to accept followers has a historically well-documented precedent in Sufism. During my time with Faruki, I witnessed only about four or five new visitors that were attempting to see if Faruki’s community was where they wanted to settle. It was evident that Faruki was not seeking to attain a high number of disciples. His emphasis was rather on quality and absolute commitment. Faruki trained his followers to be independent and responsible for their own implementation of his teachings, while he remained available to answer questions or give advice in matters ranging from everyday issues to advanced theological concepts.

The total number of attendees at any given time was about 35. Women never mixed with men, or attended ritual performances, but were considered to be dervishes. I inquired how it was possible for women to travel on the Sufi path and achieve God’s satisfaction. Faruki responded, “Every husband ought to be the Shaikh of his wife. When he comes home from the tekija, his wife ought to ask him how things went, and he should teach her.” I tried to meet with some of the female dervishes by asking their husbands for permission for an interview, but it was not allowed.

Photo 4. Some of Faruki’s Dervishes During an Ibn ‘Arabi Discussion

During meetings that he attended, I observed Faruki’s intimate knowledge of the personal lives of each member as he proceeded to give them public advice on how to solve specific problems, saying, “I am worried for them and I know everything about them that I need to know. I see them. I see how much Allah has permitted me to see and how much I need to see.” His presence was large, with everyone looking up to him and awaiting each instruction. This remarkable authority, religious expertise and attention to detail left a deep impression on his followers. Most importantly, his ruling on acceptable behaviour as well as the means of spiritual travel was influenced by his personal background and life experiences that had shaped his character and leadership style.

Faruki’s Background

Faruki was a widower with three adult children and several grandchildren. He had been born in 1941 in a small village in central Bosnia, and his father and grandmother were both dervishes. Largely self-taught, he only earned a high school diploma, but became an expert in Arabic and Islamic sciences. He translated several seminal books, including four volumes from a selection of Ibn ‘Arabi’s Meccan Revelations. He authored five books with a wide readership throughout Bosnia. His scholarly contribution, however, has been shunned by the academic community, although this did not prevent the sale of his books throughout country. During his time as an Imam, he experienced persecution by the Yugoslav secret service and was interrogated on several occasions about his loyalty to the state. While many religious leaders kept a low profile during those years, Faruki on occasion broke his silence. He illustrated with the following story:

One time I was talking, and the mosque was so full that people were standing outside. Suddenly, I got carried away and I yelled out loud that this country did not belong to Russia, America or the communists. It was God’s country! It belongs to God! One dervish in the front row was uncontrollably shaking from fear of what might happen. No other religious leader ever said what I said in Yugoslavia. And I said it publicly. But God protected me in ways that are incredible even to mention.

One of the main characteristics consistently displayed by Faruki was his passion for God. During our meetings, he avoided topics about politics or everyday matters and his sole focus was a desire to discuss matters only if they related to God. He described his love for God in the following words:

I could be dead tired and as soon as someone starts talking about God, I immediately wake up in anticipation of what will be said about my Beloved. This is simply a need that I have.

This quest to know God led him on a path of acquiring knowledge through reading books and seeking mystical experiences. Faruki’s main strength was his exceptional learning, convinced that the attainment of knowledge was paramount for the attainment of God’s nearness. All else was ancillary.

His Sufi upbringing and initiation into becoming a Shaikh was largely due to his own Shaikh Halid Salihagić, whom some considered the greatest Sufi of the last century. Faruki’s love for his Shaikh was noticeable, and old sayings by his deceased Shaikh were constantly on his lips. His devotion to his Shaikh was important, because it modelled to his followers the absolute need to love one’s leader and obey his decrees. It also highlighted the need to preserve traditional teachings of the past and follow the Shaikh in all matters of faith and practice. Shaikh Halid also introduced Faruki to Ibn ‘Arabi, a medieval thinker, whose thought provided the theological focal point of the community, and Faruki continually taught that, “We are followers of Ibn ‘Arabi… All real Sufis resemble Ibn ‘Arabi. If they do not there is something wrong with their Sufism.” Faruki insisted that it was impossible to understand Ibn ‘Arabi’s teaching without the interpretatio...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Content

- Introduction

- Exploring the Field

- The Centrality of the Shaikh

- The Theological Dimension of Guidance

- The Practical Dimension of Guidance

- Conclusion: The Study of Human Beings as a Personal Journey

- Bibliography

- BCover