- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding Resilience

About this book

Resilience has become something of a buzz word in recent years, especially in the field of member care, but what is it? This book aims to answer this and other important questions. Part one evaluates over forty years of resilience research, exploring how it has been understood in different contexts, and what it looks like in the context of cross-cultural mission. Part two reviews methods used for assessing resilience and suggests different means by which it may be enhanced.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

UNDERSTANDING RESILIENCE

CHAPTER 1

A REVIEW OF LITERATURE ON RESILIENCE

INTRODUCTION

The noun ‘resilience’ is derived from the Latin resilire, meaning ‘to leap back’. Specific disciplines have developed their own definitions of resilience: in mathematics and physics, it is defined as ‘elasticity’, or a measure of the time required for a system to return to equilibrium after being displaced; in ecology, as ‘the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and reorganize and yet persist in a similar state’ (Gunderson et al, 2006); and in social systems, as ‘the ability of groups or communities to cope with external stress and disturbances as a result of social, political and environmental change’ (Windle, 2010, p. 4).

Over the last forty years, resilience has become established as significant field of psychological research, but there is still much controversy regarding how to define it. This has been complicated further by the wide use of the term ‘resilience’ in popular literature, often in ways which are not in accordance with more scholarly definitions.

Over the last decade, resilience has become a buzz-word in the field of member care. It features frequently in member care resources, and a recent presentation described it as the ‘most important trait’ we should look for in potential cross-cultural mission workers (Cheeseman, 2015).

This chapter provides an overview of the research that has taken place into resilience over the last forty years. As member care workers, we need to make sure we talk about resilience in an informed way – so please don’t be tempted to skip this chapter! It will explain how early researchers determined that resilience is not an inherent personal quality, but a dynamic construct, based on the interaction of internal and external protective and vulnerability factors in response to an adversity. This chapter will then present resilience as one of a number of different responses to adversity, evaluating these different responses and the rationale behind them. The most important features of more recent research into the neurobiological basis of individual resilience will also be explored. A source of confusion in the resilience literature is the number of similar constructs; the most significant of these will be evaluated. Finally, having reviewed this wealth of literature, the chapter will conclude by suggesting a working definition of resilience.

DIFFERENT UNDERSTANDINGS OF RESILIENCE

Resilience as an inherent personal quality

The myth of the super-human being able to stand practically every adversity is one that has inspired people of many cultures for thousands of years. Several American resilience researchers cite the novels of the popular nineteenth-century American author, Horatio Alger, whose numerous books describe the lives of boys living at the lower end of society who through their own inherent resilience achieved material success and entered the middle classes. Western literary heritage is full of other similar examples. Early resilience research focused on identifying features and characteristics of nonfictional children considered to possess such invulnerability. However, this early research revealed, that rather than being an inherent and constant quality of an individual, resilience was a more dynamic construct dependent on the nature of the adversity itself and various factors which would either protect the individual or expose them to greater risk.

Adversity and resilience

Inferred in even the simplest definitions of resilience are two assumptions: first, that there has been an adverse event; and, secondly, that there has been an adaptive response to it. Lest we infer resilience too freely, it is important to understand what might constitute an adverse event.

Some researchers simply state that in order for resilience to be inferred, the stress that the individual overcomes has to be ‘significant’ (see Rutter, 2012, p. 336) or ‘extraordinary’ (Sameroff, 2011, p. 14). Windle provides greater clarity stating that the term resilience should not be used to refer to circumstances which for ‘a majority of people, would not ordinarily pressure adaptation and lead to negative outcomes’ (2010, p. 7). However, all these understandings of stress and adversity are subjective and prone to multiple interpretations.

What these understandings of stress do demonstrate, however, is that all of us face stressful events at regular intervals throughout our lives, such as the death of loved ones or changes in employment. One hundred years of study into the physiology of stress has provided an ever growing understanding of the stressful nature of ‘normal’ life. Stress inventories grading commonly encountered life events such as those developed by Holmes and Rahe (1967) or the Headington Institute (2015) affirm this. Such inventories have also shown that different events have the potential to result in different levels of stress, and that stressors have a cumulative effect. Consequently, these inventories provide thresholds above which psychological illness is a high possibility enabling a more objective ascription of adversity.

It is also apparent that stress can also arise from traumatic events which are far from ‘normal’: at both an individual level, such as rape or kidnapping; or on a larger scale, such as environmental disasters and civil unrest. Additionally, while many individuals may be exposed to the same adverse event (consider the many thousands of people effected by natural disasters such as an earthquake or a hurricane), the event will have a different effect on each of them depending on their geographical proximity, its impact (on them, those they love and their livelihood) and the duration of the event. Those exposed to the more severe trauma, or the highest cumulative frequency or number of threats are subject to the greatest adversity and generally show the greatest number of stress symptoms. Masten (2011, p. 497) refers to this as a ‘dose effect’.

Research has also shown that different people may respond differently to the same event; and that an individuals can respond differently to the same event at different points in their lives. Our responses are evidently not only affected by the nature of the adversity but by other factors too.

Protective and vulnerability factors

Resilience researchers have often divided the factors that govern an individual’s response to adverse events into either protective factors which contribute to a resilient response, or vulnerability (or risk) factors which hinder a resilient response. Both protective and vulnerability factors may be internal or external to an individual.

Protective factors

Many researchers have complied lists of what they consider to be the most important protective factors. Most lists are relatively brief, consisting of five or so factors, though in her concept analysis, Earvolino-Ramirez (2007, p. 75) compiled a list of nearly thirty different factors which she identified in the literature. Nonetheless, the different lists of protective factors are remarkably similar, many differences being simply due to the differing ways researchers have categorised the factors.

The seven protective factors proposed by the Headington Institute (Nolty, 2015) are used below as a basis for further discussion for two reasons: the list was formulated by a panel of experts in stress and trauma; and it was based on extensive research into resilience amongst humanitarian aid workers, a field of work with many similarities to cross-cultural mission.

Adaptive engagement

Described by other researchers as an ‘active coping style’ (Wu et al, 2013, p. 6), the ‘hardiness factor of control’ (see page 21), an ‘internal locus of control’ (Luthar, 1993, p. 9) and ‘planfulness’ (Rutter, 2012, p. 340) – adaptive engagement reflects the ability to take responsibility for one’s own life and engage with challenges when they arise. This is in contrast to the avoidance of challenge, helplessness, maladaptation or passive reactivity. Individuals who demonstrate resilience are notable by their ability to adapt to new or challenging situations and make the most of them.

Spirituality

Spirituality is defined as a ‘sense of enrichment coming from a relationship with a higher power’, usually reflected by both inner and external spiritual practices, providing a sense of hope and meaning. Other researchers describe the presence of a moral compass or a belief system to guide decisions and morality. These factors are considered to increase an individual’s capacity to deal with adversity, though it is reasonable to suggest that, if an individual’s spirituality involves a more capricious or oppressive concept of the divine, this won’t necessarily be the case.

Emotional regulation

The control of one’s emotions is beneficial in a crisis. It enables clear thinking, competent actions and patience with others. The process of cognitive appraisal, whereby people are able to monitor their thought processes and replace negative ones with more positive ones, is a means of controlling emotional responses to adversity. The positive emotions of optimism and humour are also important in enabling resilient responses as they enable the event to be reframed in a more positive light.

Behavioural regulation

The control of rash behaviour and the ability to act in careful and measured ways enables the completion of tasks and better relationships with others. Behavioural regulation also involves refraining from detrimental behaviour and good self-care skills, such as healthy drinking and sleeping habits.

Physical fitness

Increased levels of physical fitness can enhance resilience. Regular exercise increases cardiovascular health and boosts the immune system. It can also enhance social support if undertaken with others.

Sense of purpose

A sense of purpose reflects an engagement in meaningful work and positive relationships with others, both of which enable people to cope with adversity. It provides the necessary determination and responsibility to continue to engage with life in the face of adversity. Resilience is also enhanced by the sense of purpose that comes through helping others.

Life satisfaction

Those who enjoy life and find contentment seem to demonstrate greater resilience. They are able to accept life as it comes, recognising the presence of both joy and sorrow. This is often reflected by the presence of deep supportive friendships (see also page 15).

Other protective factors

As already mentioned, there are other less-cited factors which do not fit neatly into the above seven categories. These include such factors as above-average intelligence, creativity, a healthy sense of selfesteem, previous trauma experience, community acceptance, an above average memory, and even physical attractiveness.

Vulnerability factors

Just as the presence of these protective factors is associated with resilient responses to adversity, research has found that their lack is a marker of vulnerability. Research has identified many specific vulnerability factors in children, but only a few have been identified in adults, such as cigarette smoking, substance abuse, genetic predisposition, high workload, concurrent disease, and being over fifty years of age.

External factors

Protective and vulnerability factors mostly function at an individual or internal level; however, they can also be external.

Separation from others, whether physical or emotional, can be a huge source of stress; hence, the importance of social support as a protective factor is mentioned widely across resilience literature. Humans are social creatures and the relationships we form have the ability to enhance our resilience, provided they function in healthy ways; conversely, unhealthy relationships will undermine resilience. As children grow older, relationships shift from parents to close friends, and then to committed romantic partners. For people who have suffered previous adversity, the formation of such new and strong relationships can provide a break from the past and provide new opportunities.

Social support also comes through social groups such as religious groups, clubs or cliques, all social groups having the potential to provide social capacity and enable resilient responses to adversity. This is especially the case if the adversity is one that affects everyone in the community, such as a natural disaster.

An individual’s wider environment can also influence their response to adversity. For children, the nature of their school, the demographic of the children in their class, and the skill of their teachers will all have an impact, as will relationships with parents and siblings. For adults, their working environment, the quality of their line-management and relationships with colleagues are all important.

Responses to adversity are also affected by macro-level factors, such as government policy, economic climate, national infrastructure and communication.

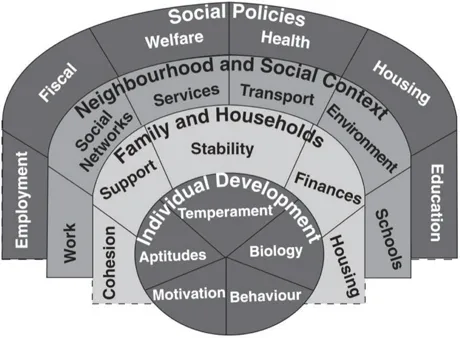

The multiple layers of factors effecting resilience are illustrated well by Windle in Figure 1 (overleaf).

It is thus apparent that resilience is not merely about the internal qualities of the individual. It is a much broader construct including the dynamic interaction between individuals and different levels of their environment. Consequently, it is possible that, although an individual might have a high capacity for resilience, their external resources may lack what is necessary to enable a resilient response to an adverse event.

Figure 1. The layers of resources and assets that facilitate resilience (Windle, 2010, p. 10)

It is for this reason that researchers prefer not to ascribe the word 'resilient' to an individual. To do so could imply that an individual did have a constant and inherent quality that enabled them to negotiate every adversity, which is not the case. As Cicchetti states, 'resilience is not something an individual "has" - it is a multiply determined developmental process that is not fixed or immutable' (2010, p. 146).

Other factors affecting resilience

Inaddition to the above protective and vulnerability factors, there are other factors which affect resilience.

Cultural factors

Insufficient work has been carried out regarding the impact of culture on responses to adversity, but cultural rituals or practices are widely assumed to have an effect.

Eggerman and Panter-Brick’s research with children and adult care-givers in Afghanistan led them to describe cultural values as ‘not just an anchor of resilience, b...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Preface

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part One: Understanding Resilience

- Part Two: Mission Spirituality

- Concluding Remarks

- Appendix: Definitions of Resilience

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Understanding Resilience by Duncan Watts in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Ministry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.