![]()

1. Defining Corruption

What is corruption? In facing this question, many believers might respond that it means all sin, perversion and evil. The first instance of the word in the Bible is used to describe the people in the time of the Flood; in other translations of the Bible, words such as ‘evil’ and ‘ruined’ are used instead of ‘corrupt’. The word ‘corruption’ in the Hebrew and the Greek which are used in the Old and New Testaments respectively, alludes to destruction, decomposition or ruin. Although Scripture does not use the word ‘corruption’ in the sense of the specific political, economic and social phenomenon referred to here, it does not mean it has nothing to offer. In fact, the Scriptures have a lot to say about this particular notion of corruption. This is the corruption that is denounced by diverse voices in the Christian church, including Pope Francis, the World Council of Churches and the World Evangelical Alliance.

While corruption is not a new phenomenon in history, there is no uniform definition of it. Thousands of pages have been written about this question, and today it continues to be a permanent topic of reflection and debate. Eric Uslaner, Professor at the University of Maryland and one of the most recognized scholars on the subject, describes corruption as an ‘elusive concept’. Even the United Nations Convention Against Corruption does not define the phenomenon, but instead simply typifies the various forms that it takes, such as money laundering, misappropriation of public funds or bribery. It is difficult to reach a full consensus on a definition, because what a society calls ‘corrupt’ will depend on its legislation, its codes of ethical conduct, its political system and public opinion.

Transparency International provides the most widely used definition of corruption: ‘the abuse of entrusted power for private gain’. Although this definition has limitations, it recognizes that corruption is not limited to the public sector but extends to the private arena, including businesses and non-profit organizations.

I would argue that corruption should be understood as a misuse of power, authority or public resources, or a breach of public trust in a broad sense and with a profound moral dimension – not purely legalistic, technocratic or conditioned by cultural relativism. Corruption implies a fundamental distinction between private interests and the common good, whereby the private concern prevails and undermines the public one. In essence, corruption entails a tension – a conflict – between private and public interests.

A broader definition of corruption reminds us that it is much more than bribery. In most societies, corruption is systemic – it is not rare or isolated. Instead, corruption is pervasive and entrenched because, while formal laws and institutions of accountability to deter and punish corruption exist, their enforcement is absent, ineffective or weak. Public officials abuse power because they are neither deterred nor controlled by state-based accountability institutions or non-state accountability actors. The term ‘corruption’ is usually associated with high-level, grand bribery or embezzlement among politicians and businesses – these are the cases that make the headlines. However, corruption is much more than that and takes many different forms. Common to all corruption practices is a violation of trust, an undermining of the common good or interests of the community or society. Each and every form represents abuses of power, trust or authority for private gain, but differs in the particular characteristics of each case.

Bribery is one of the most widely recognized forms of corruption. For example, there is the case of the Swedish telecommunications firm, Telia Company AB, that allegedly paid bribes to facilitate its expansion in the Uzbek market and in 2017 was charged with the highest penalty to date by the US government for violations of its foreign corrupt practices law. Other forms include influence peddling, money laundering and embezzlement.

Influence peddling is when someone uses their influence in government or connections with persons in authority to obtain favours or preferential treatment for another person. This can be seen in the case of the appointment of the daughter of a minister in Argentina to the position of director at the Argentine central bank for which she did not meet the legal requirements.

An example of money laundering comes from Honduras, where purchases of overvalued medicines provide a way for wealthy, well-connected individuals to make illegally sourced income appear to be legitimate.

Embezzlement is when an individual holding office illegally uses public goods or funds for their personal enrichment, as was the case in 2016 with a Malaysian sovereign wealth fund. It was alleged that more than 3.5 billion USD in assets were misappropriated by high-level officials and associates managing the fund, part of which was found in former Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak’s bank accounts in 2018.

Measuring Corruption

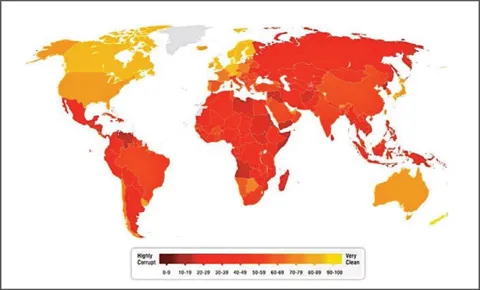

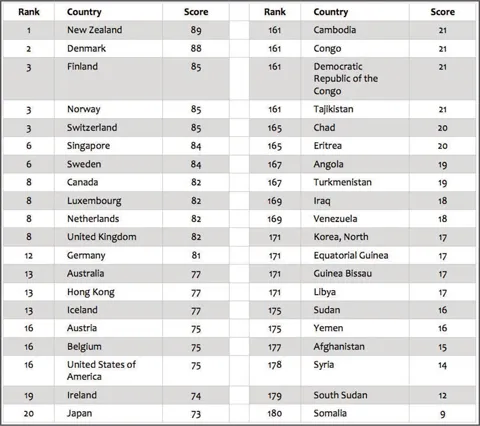

The most widely used measure of corruption is Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI). Since the early 1990s, Transparency International has issued the CPI on an annual basis. While not a perfect instrument, the CPI offers a snapshot of national levels of perceived corruption in the public sector. Every year, the CPI’s best performers rarely vary. Six countries have always ranked in the top ten positions – Denmark, New Zealand, Finland, Sweden, the Netherlands and Singapore. The vast majority of nations, however, remain virtually locked in a vicious cycle of relatively high and widespread corruption. The global results of the CPI can be seen in Figure 1 and Table 1, with more details on Christianity, perceived corruption and the amount of foreign aid to a country provided in Appendix 1: Selected Country Data.

Figure 1: Corruption Perceptions Index 2017

Table 1: Corruption Perceptions Index 2017:

Ranking of top and bottom twenty countries

![]()

2. The Costs of Corruption

Corruption is an insidious plague that has a wide range of corrosive effects on societies. It undermines democracy and the rule of law, leads to violations of human rights, distorts markets, erodes the quality of life, and allows organized crime, terrorism and other threats to human security to flourish.

– Kofi Annan, former

Secretary-General of the United Nations

The most comprehensive studies report the direct annual cost of corruption is approximately one trillion USD. In contrast, foreign aid (flows of official financing given globally) amounts to 142.6 billion USD. The cost of corruption in Africa alone is estimated at 148 billion USD a year, 25% of the continent’s gross domestic product (GDP) and about 300% of the foreign aid it receives. These figures approximate the waste of financial resources misdirected because of bribes and stolen public funds; yet the full costs of corruption are much higher than this. There are arguably no economic estimates that can fully capture the real damage of corruption on societies and their members. How does one calculate the losses for a society where children and youth come to believe that personal effort and merit do not count, and that success comes through cheating, favouritism and bribery? It is impossible to quantify the price society pays for the indirect web of impact that corruption has on society in its many forms: impunity, influence peddling, nepotism, embezzlement, bribery, extortion – and more.

Corruption has devastating effects for the social, political and economic development of nations. Corruption inhibits economic development through lower investment and productivity. Experts estimate that a worsening of one point in the CPI scale would entail a reduction in productivity of four percentage points in GDP, while a six-point improvement in the CPI would imply approximately 20% growth in GDP.

Along with the United Nations and other international organizations, Christian leaders and institutions have increasingly recognized the devastating effects of corruption. In 2006, in a conference conducted in the Vatican about the fight against corruption, the Catholic Church, through its Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, recognized the gravity of corruption and its effects when referring to it as an act that is ‘a very serious fact that distorts the political system’. The conference note went on to say: “Corruption causes serious harm from a material point of view and places a costly burden on economic growth; still more harmful are its effects on immaterial goods, closely connected to the qualitative and human dimension of life in society.” The World Evangelical Alliance and the Micah Network, in the launch of ‘Exposed’, a global campaign against corruption, recognized the negative consequences in all aspects of development.

The Cost to Human Development

Although the full range of adverse impacts is difficult to track, we can see the effect of corruption by zooming into particular cases. Investigators of the magnitude 7.0 earthquake on 12 January 2010 in Haiti reported that the combination of the size of the earthquake and the widespread corruption throughout the country was responsible for such a devastating impact: 100,000 to 300,000 deaths and 1.3 million people left homeless. In contrast, just seven weeks later, a magnitude 8.8 earthquake (500 times more powerful than the earthquake in Haiti) hit two port cities in Chile. However, less than 500 people died and the material damages were minimal. Though there were certainly differences between the two cities’ epicentre location, population density and type of earthquake, corruption in Haiti surely had an effect. The use of low-quality building materials and limited public access to construction equipment and medical supplies were, in many cases, directly linked to bribes and the misappropriation of public funds. In 2010, Haiti’s Corruption Perceptions Index was 2.2/10 and Chile was 7.2/10. Estimates show that, over the past thirty years, 83% of deaths connected with earthquake-related building collapses took place in countries with endemic corruption.

Country-specific research confirms that corruption has measurable local impacts on specific health and education outcomes. A Philippine-specific study showed that corruption decreased immunization rates and national test score levels, increased national test score variation and even measurably increased wait times at hospitals. Research in Tanzania found that the health workers created artificial shortages and deliberately lowered the quality of service in order to extract higher payments from patients, or increased their leverage in bargaining, which led to more expensive and lower-quality health care, as well as inducing non-corrupt health workers to reduce their quality of care.

A global econometric study found that a single one-point decrease in the CPI (indexed from 0 to 100) is associated with about a 10% decrease in secondary school enrolment rates (for scale, on the CPI 2017, Norway scored 85, United States scored 75, Bahamas scored 65 and Rwanda scored 55). Another study found that 1.6% of all deaths of children under five can be indirectly attributed to corruption. This means 140,000 children die because of corruption, compared with the familiar killers of malaria (306,371 deaths of children under five), HIV/AIDS (986,724 deaths) and measles (73,848 deaths). These econometric studies are but a few quantitative evidences of the diverse and deep effects of corruption on society.

The Cost to the Poor

Tragically, the poor and marginalized suffer the worst consequences of corruption. The World Bank affirms that corruption is ‘the greatest obstacle to reducing poverty’. Corruption affects poverty by slowing economic growth, exacerbating the poverty and inequality already present. Likewise, corruption deepens poverty through its negative effect on governance of weakening institutions, reducing citizen participation and reducing the quality of public services and infrastructure.

The poor suffer from less accessible public services, which are not only lower quality, but also more expensive than what is accessible to the rest of society. The poor struggle daily against the pressure to pay bribes to access basic public services like hospitals, medicine and public infrastructure. Corruption directly extracts money from the poor because they are powerless against the pressure. Poor people pay larger shares of their income in bribes than richer people and are specifically discriminated against in their access to public services. A leader of the evangelical Christian NGO Tearfund shares: “We know from our work in Africa, Asia, and Latin America that it is the poorest and most vulnerable people who suffer the most as a result of bribery.” Worse, the poor are denied public help, such as housing or subsidized credit, because those benefits are illegitimately assigned to people with greater leverage. Facing a situation in which the public service is of a lower quality, the poor opt for even more expensive private options.

Corruption undoes and prevents all forms of development that are for the benefit of the poor. Resources intended for the poor, including foreign aid, do not reach the people that need it, but are diverted to enrich corrupt elites. Diversion of funds, unfair preferential contracting, money laundering, extortion – all forms of corruption – stifle global development from the start. Additionally, whatever public money is spent for public use in countries with higher levels of corr...