eBook - ePub

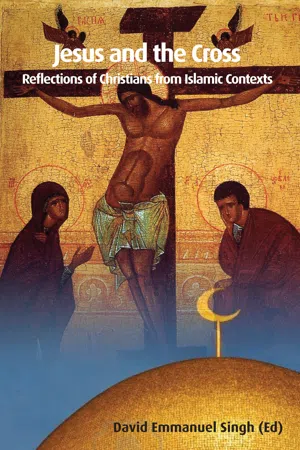

Jesus and the Cross

About this book

The papers in this volume are organised in three parts: scriptural, contextual and theological. The central question being addressed is: how do Christians living in contexts where Islam is a majority or minority religion, experience, express or think of the cross? This is therefore an exercise in listening. As the contexts from where these engagements arise are varied, the papers in drawing scriptural, contextual and theological reflections offer a cross-section of Christian thinking about Jesus and the cross.

Information

PART ONE

THE CROSS IN THE SCRIPTURES

ECCE, AGNUS DEI: THE CROSS IN THE OLD TESTAMENT

Jules Gomes

Rev Dr Jules Gomes is Coordinating Chaplain to the Old Royal Naval College, University of Greenwich and Trinity College of Music, London

‘As he (the Lamb) spoke his snowy white flushed into tawny gold and his size changed and he was Aslan himself, towering above them and scattering light from his mane.’ C.S. Lewis, The Voyage of the Dawntreader.

If the crux Christi is the apex of Christian belief and practice, and if the Christian New Testament is understood to be in theological, thematic and even textual continuity with the Hebrew Old Testament, is it possible to legitimately discover the crux of Christian faith in the crucible of the Hebrew Bible? The apostolic witnesses were confident that they could credibly construct the gospels as the fulfilment of the Hebrew Scriptures. This is especially seen in the passion narratives where attention has been paid to meticulous detail in drawing parallels between the passion narratives and OT texts1 dominated by images of the suffering Patriarch (Genesis 22),2 the suffering Prophet or the Servant (Isaiah 53)3 and the suffering Psalmist (Psalm 22).4 The gospel writers thus seek to portray the crucified Christ as the fulfilment of the entire Hebrew Bible - the Law, Prophets and Writings (cf. Luke 24:27).

But tracing the relationship between God’s revelation in the Old Covenant and the New Covenant has never been trouble-free: ‘Though it may seem hard to believe, the fact is that this basic and important question has scarcely been given a clear answer over the past twenty centuries of Christian living. And that fact has conditioned the whole of theology.’5 Models of salvation history, tradition history, typology, promise and fulfilment, and continuity and discontinuity have been suggested as bridges across the exegetical impasse.6 One possible way of exploring a relationship between testaments is by association - identifying an important OT metaphor, theme, text or tradition that in the NT is so closely linked to the cross that it acts as a metonymy for the cross. After examining the legitimacy of the NT link, this theme or text can then be studied in its historical OT context and its meaning there discovered without arbitrarily superimposing later NT interpretations.7

An example of this is the representation of Jesus as the Lamb, which the gospel of John identifies with the crucified Christ.8 In the fourth gospel, the Baptist introduces the first disciples to Jesus using the metaphor of the Lamb: ‘Behold, here is the Lamb of God!’ (ecce, agnus dei!) (John 1:36). Jesus has already been introduced as ‘the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world’ (John 1:29).9 The Lamb is also alluded to in the passion narrative: at a time that is a few hours before the Passover meal (19:14-16), Jesus (the Lamb) is handed over to be crucified. The passion narrative concludes with the reference to the OT: “These things occurred so that the scripture might be fulfilled, ‘None of his bones shall be broken’” (19:36). This is again a reference to the Passover Lamb (Exodus 12:10, 46; Numbers 9:12).10

It is also significant that the fourth gospel is intent on associating the Lamb with the OT Messiah. John’s intention is primarily to show that Jesus really is the Messiah and the Son of God (John 20:31). The response to the Baptist’s introduction of Jesus as the Lamb is the ‘eureka’ declaration of Andrew to Simon Peter: ‘We have found the Messiah.’ The declaration uses the Aramaic/Hebrew for Messiah, followed by a telling editorial note translating the term into Greek (John 1:41). The primary characterisation of Jesus as the ‘Christ’ (Messiah) is central to the relationship between the Testaments.11 Hence, one way of attempting to study the ‘cross’ in the OT would be to examine the imagery of the Lamb in the Hebrew Bible.

Furthermore, early church tradition gives some justification to proceed in this direction. Justin Martyr depicted the paschal lamb as being offered in the form of a cross and claimed that this prefigured the crucifixion of Jesus. While Justin Martyr may have been thinking of the Samaritan Passover of his day, rabbinic evidence seems to show that in Jerusalem the Jewish paschal lamb was offered in a manner that resembled crucifixion.12

A Jew familiar with Hebrew traditions would detect in the catchphrase ‘Lamb of God’ a theological concept that spanned the scope of scripture. In Genesis, the lamb features in the story of Abraham and Isaac on Mount Moriah. In Exodus, the blood of the Passover lamb was applied to the doorposts of the Hebrew slaves in Egypt. In Leviticus, the sacrificial lamb was used in the burnt offering. In Isaiah, the lamb is the Suffering Servant of Yahweh who is led to slaughter. In the inter-testamental book of Enoch there is the image of a lamb sprouting a great horn, and battling with the enemy.

The story of Genesis 22:1-19, where a lamb is sacrificed in place of Isaac, starts a series of other ‘Lamb’ traditions in the OT. A few preliminary points may be noted. The literary placement of the story in Genesis 22:1-19 acts as a climax to the Abraham cycle by making Abraham pass the supreme test of faith. The Elohist’s version of the story is without parallel in the Yahwist.13 There is a debate as to whether vv.15-18 are a later addition;14 I believe it to be part of the original story since it is both Abraham’s obedience and his faith in God’s promises which is being tested (cf. Hebrews 11:17). The reiteration of the promises to the obedient patriarch is well deserved.

In Genesis 22:7 the Hebrew word used is ‘sheep’ (seh) which is used almost synonymously for ‘ewe’ (rahel). This is seen in Isaiah 53:7: ‘like a lamb (seh) that is led to the slaughter, and like a sheep (rahel) that before its shearers is silent….’ However, what is then provided for the sacrifice is the ‘ram’ (Genesis 22:). In Akkadian shu’u is used for ‘ram’ and in Ugaritic ritual texts it is limited to ‘ram’ or ‘he-goat’; elsewhere its use is more general, encompassing both sexes.15 The LXX translates the word as probaton, which is in Greek used in the widest sense to denote all four-footed animals especially tame, domestic ones. The word used for Jesus as lamb in John’s gospel is amno (John 1:29, 36, Isaiah 53:7 LXX, cf. Acts 8:32, 1Peter 1:19). However, the primary use of the Hebrew seh (sheep) and its use elsewhere for a clean animal that may be eaten (Deuteronomy 14:4) and offered for a sacrifice; whose firstling belongs to Yahweh (Exodus 34:19; Leviticus 27:26), is to be roasted for the Passover meal (Exodus 12:3ff), is suitable for a guilt offering or a burnt offering (Leviticus 5:7; Leviticus 12:8) and is led silently to the slaughter (Isaiah 53:7) is sufficient to identify it with the lamb in the NT.

When examining specifically the function and meaning of the lamb in the ‘binding of Isaac’ story it is interesting to note that in the history of religions in Western Asia the ‘lamb’ is identified most closely with the human being since it is the most domesticated of all animals. “Sheep need human care as humans need human care, and this isomorphism of need proved a powerful stimulus to the religious imagination first of Ancient Israel and later of early Christianity,” explains Miles.16 “The equation of sheep with man is striking as well in the story of the binding of Isaac. ‘God will provide the lamb,’ Abraham says to Isaac (Genesis 22:8), all the while expecting to slay his son. Isaac believes his father, trusting just as the lamb, anthropomorphized, seems to trust when it is led unresisting to the slaughter ground.”17 It has been suggested that the story was originally an aetiology formally rejecting human sacrifice and explaining why it was no longer permissible in Israel.18 Human sacrifice was supposed to expiate past transgressions and possessed a redemptive character. It also brought about atonement.19 The term olah (Genesis 22:2) was also used to refer to child sacrifice (2 Kings 3:27). A judge like Jephthah sacrifices his only child - a virgin daughter - because of the vow he has made (Judges 11:34-40, cf. 2 Kings 17:17, Micah 6:7).20 Snyder suggests that Abraham and his men reject the contemporary idealization of human sacrifice as the highest form of worship and so their proud and open return to the community becomes an exceptional act of courage.21 The lamb, being closest to the human, could be thus seen as the ideal substitute or scapegoat that was killed in the place of the slaying of a human being.

In the Genesis story we are faced with an individual and not a communal sacrifice. Abraham is to offer Isaac as a ‘whole burnt offering’ olah (22:2); literally ‘an offering of ascent’ or an ‘ascending offering’. This was so called because the sacrifice was entirely burnt on the altar and its smoke ascended to the heavenly deity. This type of offering was the most widespread in ancient Israel - the phrase ‘burnt offerings and peace offerings’ could be used as merism for the entire sacrificial system.22 Milgrom has argued that the ola was the earliest form of atonement sacrifice in the biblical materials.23 Job 1:5 is good evidence of this: “Job would rise early in the morning and offer burnt offerings according to the number of (his sons) for he said: ‘It may be that my sons have sinned and cursed God in their hearts.’” In Leviticus 1:4 it is said that the burnt offering ‘shall be acceptable in your behalf as atonement for you’. In this case, what is Abraham making atonement for, if such is indeed the case?

Wenham convincingly demonstrates the literary parallel between the story of Abraham and Isaac (Genesis 22:1-19) and the preceding story of Ishmael’s expulsion, but does not explain why the editor has dovetailed the two narratives as parallels.24

Ishmael | Isaac |

God orders Ishmael’s expulsion (21:12-13) | God orders Isaac’s sacrifice (22:2) |

Food and water taken (21:14) | Sacrificial material taken (22:3) |

Journey (21:14) | Journey (22:4-8) |

Ishmael about to die (21:16) | Isaac about to die (22:10) |

Angel of God calls from heaven (21:17) | Angel of the LORD calls from heaven (22:11) |

‘Do not fear’ (21:17) | ‘fear God’ (22:12) |

‘God has heard’ | ‘You have obeyed (heard) my voice’ (22:18) |

‘I shall make into a great nation’ (21:18) | ‘Your descendants will be like stars, sand,’ etc. (22:17) |

God opens her eyes and she sees well (21:19) | Abraham raises his eyes and sees ram (22:13) |

She gives the lad a drink (21:19) | He sacrifices ram instead of son (22:14) |

The background is the conflict between Sarah and Hagar for which Abraham is held responsible. Indeed, the term Sarah uses for the ‘wrong done to me’ (Genesis 16:5) is hamas which is best translated ‘violence’ and is used elsewhere in the flood story to describe the earth ‘filled with violence’ which is why God decides to destroy the earth (Genesis 6:11,13).25 It is not improbable that the story of Isaac’s binding and the offering of the lamb in his place was intended as a means of resolving the conflict between the descendants of Isaac and Ishmael, at least in an earlier version. The story concludes with Abraham and his ‘young men’, presumably including Isaac, returning to Beersheba and living there (Genesis 22:19). The name of the place is mentioned twice in v. 19; earlier Abraham has sent Hagar away and she is left wandering in the wilderness of Beersheba (Genesis 21:14). Midrashic readings narrate how Ishmael accompanied Abraham and Isaac to Mount Moriah to witness the Akedah (Genesis 22).26 When he dies Abraham is buried by Isaac and Ishmael (Genesis 25:9). The sons of Ishmael are accorded almost equal honour as ‘twelve princes according to their tribes’ (Genesis 25:16). This time it is the Priestly source or redactor who places the two sons together but without a word of explanation.

The role of Isaac as potential victim is also important. He is an example of a righteous sufferer - facing the possibility of a violent death for no fault of his own. He does not fully understand what is going on; although it is hardly conceivable that Abraham’s tense demeanour would have not betrayed his foreboding. ‘The fire and the wood are here, but where is the lamb for a burnt offering?’ he asks (Genesis 22:7). Like a lamb that is silent before its slaughterer, the text does not record his protest but only his silence.

The literary turning point of the story is the halting of the human sacrifice and the p...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Part One: The Cross in the Scriptures

- Part Two: Reflections from Contexts

- Part Three: Theological Reflections

- Bibliography

- Subject Index

- Name Index

- Place Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Jesus and the Cross by David Singh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Ministry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.