![]()

Introduction

Two Big Questions

Everyone should be concerned about extreme economic equality, because it affects a country’s chances of eradicating extreme poverty. It does this in two ways. First, extreme inequality of incomes and of land ownership retards economic growth1 (though there is some evidence that moderate inequality in richer countries is associated with economic growth there).2 Second, for a given level of economic growth, countries with less equal distribution of incomes tend to experience a smaller reduction in poverty.3 So countries with extreme inequality tend to stay poor as a whole, and their poorest citizens are especially unlikely to escape poverty.

Before going any further I need to address a possible misunderstanding about inequality. Inequality is not necessarily a result of unfairness (though it may be). In some situations inequality reflects fair rewards for natural talent and hard work. Some people with right-of-centre politics were initially wary when I discussed this research with them, because they assumed I must be a socialist if I was concerned about inequality. However, as you will see by the end of Chapter 2, this book is not about whether governments are left-wing or right-wing, but about whether they are accountable or corrupt. So please do not stop reading if you disapprove of socialism. There is something important here for everyone, whatever their politics.4

This book addresses two big questions. Why is economic inequality greatest in Christian, and especially Protestant, developing countries? And can the church reduce those economic inequalities? Before reading anything about my answers to those questions you probably want to know a little about me and the perspective from which I approached them. I am a Protestant Christian and most of my close relatives are Anglican clergy. I am male, middle aged, and married with three children. I am a British GP and public health specialist, and I have worked in India and Nepal as a GP and public health specialist for ten years. My interest in this subject developed as I tried to understand poverty while working in Asia, and most of the research presented in this book was done while my home was in Kathmandu.

You would be right to ask whether my answers to the two big questions are biased by my own Christian faith. My reply is that I tried to let my opinions be guided by the evidence rather than vice versa and the verdict of the external examiner at my PhD viva, who is not a Christian but was a professor of economics at the University of Oxford, is reassuring on that point. Regarding the statistical material in Chapter 2 he wrote that ‘care is taken to evaluate the evidence using appropriate criteria’, and his assessment of my handling of all the interview material was that ‘it is interpreted carefully and without any obvious bias’. In Chapter 4 I have described how I designed and conducted the four country case studies, so that you can decide for yourself whether you think they provide a valid account of the situation in those countries.

My Initial Research Journey

When I first considered taking this on as a research project in 2001 I was two years into a nine year period working in Nepal, a poor country that until 2006 was officially a Hindu state. Throughout that period I was employed by Interserve, a Protestant missionary society. Implicitly or explicitly, many of my colleagues took the view that a Christian worldview helps to reduce poverty. An example of this view is given by Darrow Miller:5

Many have noticed, perhaps for the first time, that the lands with the least access to the gospel are also the neediest … Physical poverty doesn’t just happen. It is the logical result of the way people look at themselves and the world, the stories they tell to make sense of their world. Physical poverty is rooted in a mindset of poverty, a set of ideas held corporately that produce certain behaviours. These behaviours can be institutionalised into the laws and structures of society. The consequence of these behaviours and structures is poverty.

However, some surprising evidence was emerging that Christianity is associated with extreme economic inequality, particularly in countries where democracy is weak;6 and since extreme economic inequality tends to keep the poorest people poor, this is bad news for anyone who thinks a Christian worldview might help to reduce poverty. My own introduction to the surprising connection between Christianity and extreme economic inequality came during a medical lecture in Kathmandu in 2001. The speaker was describing the well-known observation that egalitarian societies tend to enjoy relatively good health, even if they are quite poor overall. He cited the example of the state of Kerala in southwest India, which is poor but has low levels of inequality, good child survival and long life expectancy. At various points over the previous 20 years I had read about Kerala in books by Christian authors, all of whom attributed these characteristics to Kerala’s long history of Christianity (the Mar Thoma church there believes that Saint Thomas founded a church in Kerala in the first century AD).

Imagine my surprise when the speaker (who is not a Christian, as far as I know) concluded his description of Kerala by attributing the egalitarian nature of its society to its long history of socialist and communist governments. Keen to demonstrate that his interpretation of the data must be flawed and that Christian heritage should take the credit, I set about compiling some published statistics on Christianity and economic inequality in different parts of the world.

The Statistical Association between Christianity and Economic Inequality

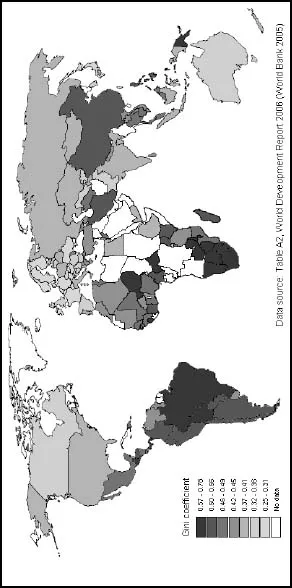

I ended up with a map similar to Figure 1.1. The map shows how the Gini coefficient for the distribution of consumption varied between countries in, or close to, the year AD 2000.7 As you can see, the most unequal countries are in Latin America (which is mainly Catholic), sub-Saharan Africa (which is largely a mixture of Protestant and Catholic), plus the Philippines (Catholic), Papua New Guinea (Protestant), Iran (Islamic) and China.8 The most economically egalitarian countries are in northern Europe (historically Protestant).

Although many Islamic countries do not report any data, nearly all of those that do appear to be quite egalitarian economically: Senegal, Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, Jordan, Turkey, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Malaysia and Indonesia. The only notably unequal Islamic countries are Niger and Iran.

A World Bank Policy Research Working Paper was the first publication formally to demonstrate that economic inequality is greatest in Christian, and especially Protestant, developing countries.9 Although I disagree with them, the authors interpreted this as evidence that religion may be an important determinant of inequality - in other words, that Christianity causes inequality, at least in countries where democracy is weak.

To me as a Christian, the observation that economic inequality tends to be greatest in Christian developing countries was shocking. Extreme economic inequality seems incompatible with Jesus’ command to ‘love your neighbour as yourself’.

Figure 1.1 Gini coefficient of income distribution c. AD 2000

An early practical application of Jesus’ teaching can be found in Saint Paul’s second letter to the church at Corinth, where Paul was clearly sympathetic to the plight of a community that had fallen on hard times (II Corinthians 8:13-15):

Our desire is not that others might be relieved while you are hard pressed, but that there might be equality. At the present time your plenty will supply what they need, so that in turn their plenty will supply what you need. The goal is equality, as it is written: ‘The one who gathered much did not have too much, and the one who gathered little did not have too little.’

The map presented in Figure 1.1 shows that Jesus’ teaching has had little effect in countries where most people describe themselves as his followers. Worse than this, the gap between those who ‘gather little’ and those who ‘gather much’ is actually greatest in countries where a majority of people are Christians. Whatever Christian charitable activities may be going in those countries (and there have always been plenty of them in every country I have visited), they are failing to address the gap between rich and poor. Could it even be, I asked myself, that, by propagating a Christian worldview, the activities of Christian missionaries are unwittingly contributing to greater economic inequality, and hence greater poverty?

Reasons for Doubting that Christianity Causes Economic Inequality

For the first couple of years after starting this research project I was unsure whether the association between Christianity and economic inequality represents cause and effect, but eventually two observations made this seem unlikely.

First, it is very difficult to attribute the apparent economic equality of Nepal and India (see Figure 1.1) to their prevailing Hindu religion. I spent nine years living in the Hindu kingdom of Nepal, where I experienced on a daily basis the importance of recognizing social hierarchy by using the correct form (high, middle or low) every time you address other people, and I saw at firsthand how the Hindu caste system reinforces a strong social hierarchy where everyone has their expected position and role. Our upper caste landlord was appalled when he saw me watering the garden: ‘It is not right for a doctor to do this. You must hire a gardener’.

A Hindu author has written that Hinduism ‘believes in the innate inequality of all men … The first step towards a reconstruction of the Hindu philosophy of morals would be to challenge the organisation of society on the basis of hereditary castes and the practice of untouchability.’10 The Hindu view of innate inequality is reflected in data on the relationship between religious adherence and contemporary attitudes towards economic inequality. Data from the World Values Survey show that Hindus are more likely than any other religious group (Protestant, Catholic, Buddhist, Muslim or Jew) to support incentives for effort over equality of incomes.11 So it is implausible that the relatively egalitarian economies of India and Nepal can be attributed to their Hindu religion; and if religion is not a strong determinant of economic inequality in India and Nepal, it seems unlikely that it is a strong determinant of economic inequality anywhere else.

My second reason for doubting that the association between Christianity and economic inequality is causal was an alternative explanation that emerged as I was reading some research that has nothing to say about religion at all, but deals instead with land abundance as an underlying cause of economic inequality.12 Brief inspection of the list of countries included in those authors’ dataset revealed that land abundant countries tend to be Christian, while land scarce countries typically are not. This suggested that religion might be associated with the true causes of economic inequality, but not be a cause of inequality itself. Chapter 2 presents the evidence that this is indeed the case.

When you have read that chapter you will see why I tightened up my second question from the rather general ‘Can the church reduce economic inequalities?’ to focus on the church and corruption. The analysis in Chapter 2 shows that reductions in corruption in any country should reduce economic inequality by ensuring that a greater proportion of government revenue is used to benefit the majority of the population rather than ruling elites. The opportunity for reducing inequality by reducing corruption is particularly great in Protestant developing countries, because they have relatively large governments. Not only is the impact on economic inequality of controlling corruption likely to be greater in Protestant developing cou...