eBook - ePub

Gap and Eul

About this book

Patronage governs most relationships in Global South cultures. However, regrettably, missionaries rarely recognise this prominent cultural reality. Moreover, misunderstanding patronage creates problems not only for missionaries but also for national pastors. This book shows that when a patron plays a role as a father, he plays a significant role in developing national pastors as church planters and offers an alternative reading of aid dependency as a relational concept rather than an economic one.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1. Introduction

1.1 Introduction

This book is the result of my PhD research on Cambodia from 2009 to 2018. The impetus for my research began with a desire to understand why Cambodian churches planted by Korean missionaries in Cambodia are not becoming self-sustaining, unlike my prior church plant in Siberia, Russia.

At the Phnom Penh Symposium in 2010, Jinsup Song, a mission superintendent of the Korean Methodist Churches of Cambodia, pointed out the problematic dynamics in church-planting efforts as he was sharing financial data from his denomination’s annual report. He quantified that by 2011, after more than 15 years of mission work in Cambodia, the financial support needed for 150 Cambodia churches planted by Korean Methodist missionaries had reached $16,000 per month, including salaries and facility-renting fees. However, none of these 150 churches was financially self-sustaining. He reported that the monthly budget was increasing at a rate higher than the next generation of Methodist seminary graduates can church-plant for. As a direct result, their future church-planting projects were placed on hold, and they were reorganising their future mission strategy to include the development of self-sustainable components such as capacity building and leadership training.

One interview in 2011 changed the direction of my research. A director of an established Bible college in Cambodia – an American missionary and one of my key informants – shared this story. He was hosting their annual pastors’ meeting with about 300 Cambodian pastors, most of whom were graduates of his college. The Cambodian pastors were asked to share some of the difficulties they faced in their ministries. The majority testified that the most difficult problem they faced was engaging with ‘Korean missionaries’. At the end of their meeting, they decided to write a formal letter to the Cambodian government to request the expulsion of all the Korean missionaries from Cambodia. However, after more discussions and persuasion, including the director’s intervention, their plan did not materialise.

As a Korean American I was surprised to hear such news. I was born in South Korea, but raised and educated in Los Angeles because my family emigrated to the US when I was 12 years old. I have lived in the US for more than 40 years, in a multicultural setting. As a bicultural and bilingual person, I thought I could better understand the conflict between Korean missionaries and Cambodian pastors. Thus, I asked the director for specific reasons and more detailed information. He shared how one of his Bible college graduates, ministering at a remote village in Cambodia for more than ten years, had a Korean missionary visiting his church who wanted to help out with the poor members of the church with monthly rice distribution. Thinking that the Korean missionary was merely engaging in mercy ministry, he allowed the rice distribution.

After several months, however, the Korean missionary built a church building next to the Cambodian church and announced to the members that if they wanted to continue receiving the rice, then they would have to come to the new church. According to my informant, his former student sat before him, wept, and reported that most of his church members left and joined the Korean missionary’s church. He asked, ‘Why are Korean missionaries here!’, expressing his frustration and insinuating his disapproval of Korean missionaries in Cambodia.

Similar complaints had already been made against Korean missionaries at a focus group meeting I attended in 2010. During the discussion about the possibility of doing self-sustaining ministry, one of the Cambodian pastors complained, ‘Korean missionaries treated us like employees and acted like our boss from the beginning, so why do you want us to become financially independent now? Do you work for your company for free?’

On another occasion, at a Cambodian pastors’ meeting in which I participated as an observer, one young Cambodian pastor approached me after realising that I was Korean, and complained in English with visible anger, ‘Why are Korean missionaries here? They are taking my church members by bussing them out of my village!’ It was part of the ‘Mission Kampuchea 2021’ regional meeting held in Phnom Penh in 2013. At the end of the meeting, some young Cambodian pastors demanded floor time for two issues on the agenda regarding the ‘problem with Korean missionaries’, and they showed anger and frustration.

However, one of the founding leaders of that organisation intervened and requested that they postpone that agenda for the next meeting, being aware that there were several Korean missionaries present at that gathering. These episodes informed me that my research focus on aid dependency alone, especially on financial dependency, would not adequately address the relational and emotional problems between Korean missionaries and Cambodian Christian leaders.

1.2 Purpose of the Book

Patronage governs most relationships in Global South cultures. However, regrettably, missionaries rarely recognise this distinct cultural reality. Moreover, misunderstanding patronage creates problems not only for missionaries but also for national pastors. This book endeavours to demonstrate that when a patron plays a role as a father figure, he plays a significant role in developing national pastors as church planters and offers an alternative reading of aid dependency as a relational concept, rather than an economic one.

Based on the research data, this book attempts to answer this question: How does the patron–client dynamic between Korean missionaries and Cambodian church planters offer an alternative understanding of aid dependency within the discourse of mission studies? The patron–client relationship has been a popular concept in socio-political studies. Although there is evidence to show that a patron–client network and co-operation among small informal groups are prevalent in Cambodia (Ledgerwood, 1998), its role is not clear because it has not been sufficiently explored within the context of Korean missionaries working with Cambodians.

In this book, I aim to analyse the patron–client relationship between ‘Ted Kim’ – patron and founder of the Cambodia Bible College (CBC) – and CBC pastors as clients. Ted Kim is not his real name but a generic name for anonymity, which was specifically requested by Ted. Therefore, all the Cambodian names, locations and church names have been changed for anonymity.

I focus specifically on the tripartite roles of patron and clients in various church-planting stages to learn more about the problem of aid dependency. This book portrays the lifecycle stages of a father, supporter and partner – through protection, provision and equality respectively. The dependency levels between these two groups correspond to the life stages of their relationships.

The significant contribution of this book will be to offer a new interpretation of aid dependency in the context of Korean missionaries and Cambodian church planters, within the context of the CBC by researching relationships, as Ted acted as a patron father. Also, uncovering new data collected through CBC pastors’ narratives at the grassroots will contribute different and fresh insights into ongoing debates on aid dependency in missiology.

2. Patron–Client Relationship Issues

2.1 Introduction

I have learned that patron–client dynamics between Korean missionaries and Cambodian Christians are foundational components in their relationship. I ask, ‘How does the patron–client dynamic between Korean missionaries and Cambodian church planters offer an alternative understanding of aid dependency within the discourse of mission studies?’ I chose the CBC church-planting project as the case study to examine relationship dynamics between Ted Kim (hereinafter, Ted) and the CBC pastors.

2.2 Patron–Client Relationship in Social Anthropology

First, I attempt to define what the patron–client relationship is in a social anthropological study. Although Western European feudal societies revolved around what one could term patron–client relationships, and there may be some examples in other civilisations, the patron–client relationship was first studied and published in the field of sociology by Shmuel Eisenstadt in 1956 in an article entitled ‘Ritualized Personal Relationship’. In his analysis of the patron–client relationship, he was convinced that ‘such relations are sign not just of underdevelopment, but of special types of social formations closely related to specific types of cultural orientations’ (1984: ix).

According to Johan Lindquist, the significant anthropological interest in the patron–client dynamic and brokers ‘does not emerge until the post-colonial era during the 1950s and 60s’ (2015: 2). Eisenstadt also argues that from the late 1950s, patron–client relationship studies became more central to sociological and anthropological analysis because of the growing awareness that patron– client relationships were not destined to remain on the outskirts of society or to disappear with the development of democratic governments, economic developments and modernisation, ‘but new types of patron-client relationship may appear seemingly performing important functions within such more developed modern society’ (1984: 4).

Important articles by Eric Wolf (1956) and Clifford Geertz (1960) explicitly developed the idea of the cultural broker to describe changing forms of political authority and the transforming relationship between villages and cities following decolonisation in Mexico and Indonesia. F.G. Bailey identified patron brokers as ‘agents of social change’ (1963: 101), integrating villages into a broader society in India. These papers attempted to elucidate the development of new forms of political and social relationships through the figure of the patron as a broker.

The terms ‘patron’ and ‘client’ originated when the common people of ancient Rome, plebeians (clientem), were dependent upon the ruling class, patricians (patron), for their welfare (Gordon Marshall, 1998). At that time, the client was a person who had a lawyer speaking for them in a trial. In court, this meaning still stands today. At the same time, ‘clientela’ was a group of people who had someone speaking for them in public, the ‘patronus’ (Muno, 2010: 3).

The patron–client relationship is not unique to Cambodia but is fundamentally an issue related to any levels of development, and so unsurprisingly it also appears in references to South America, Africa and Europe – especially in agricultural societies. Until recently, the use of patron–client analysis has been the domain of anthropologists, who found it particularly useful in penetrating communities where interpersonal power relations were most noticeable. Terms that are ‘related to patron-client structures in the anthropological literature include “clientelism”, “dyadic contract”, and “personal network”’ (Scott, 1972: 92).

The patron–client relationship is a social relationship between two persons: patron and client. A patron controls specific resources such as money, goods, access to jobs, and services. These resources are available for the client under certain circumstances. The client has to give their resources such as work or support. Nevertheless, they have a close personal relationship with the patron (Muno, 2010: 4). The patron is always at the top of this dyadic network, and the client(s) is/are at the bottom.

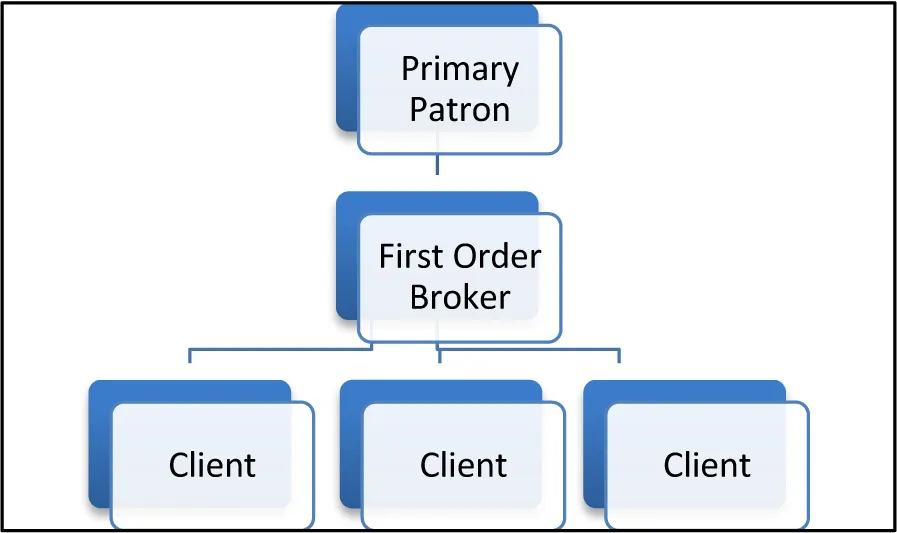

James Scott calls this ‘the patron-client pyramid’ – enlarging on the cluster but still focusing on one person and their vertical link. This is simply a vertical extension downwards of the cluster in which linkages are introduced beyond the first order (1972: 96), as shown in Diagram A below.

Diagram A: Patron-Client Pyramid

In reality, the First Order Broker (FOB) performs as both patron and client. The FOB receives resources from the primary patron and, in that sense, they are clients. However, these resources are often managed and distributed quite independently, and practically the FOBs control these resources, so they become patrons for other clients. The remarkable aspect of this patron–client pyramid is that there is always a dyadic relationship between patron and client at its core (Muno, 2010: 6).

In the context of Korean missionaries and Cambodian Christians, there is another patron (the primary patron) on top of the patron (Korean missionaries). In this way, Korean missionaries become the broker to the primary patron. Practically, there may be several levels of brokers. For example, the sending mission agency of a denomination, e.g. the Methodist Church of Korea, may be the primary patron, but then there are the brokers, and ‘at the end of the stick’ are the clients. Brokers with direct contact with clients are the first order of brokers. Korean missionaries play the role of the FOBs to Cambodian Christians, their clients.

This pyramid type of patron–client clusters is one of several ways Cambodians who are not close kin come to be associated. J. Scott states that ‘most alternative forms of association involve organising around categorical ties, both traditional – such as ethnicity, religion, or caste – and modern – such as occupation or class – which produce groups that are fundamentally different in structure and dynamics’ (1972: 97). The patron–client pyramid is observed in many of the Korean missionaries’ mission structures. The primary patron is either a church or denomination from Korea, and Korean missionaries take the role of the FOB, and become the connector to Cambodian Christians with finances and other resources coming from Korea.

2.2.1 Patron as a Broker

In anthropology, the cultural broker appears as a starting point for considering social change more broadly. Wolf defines brokers as ‘groups of people who mediate between community-oriented groups in communities and nation-oriented groups which operate through national institutions’ (1956: 1,075–6).

In the field of social and cultural anthropology in the 1950s–1960s, Wolf (1956) and Clifford Geertz (1960) saw brokers as ‘cultural brokers’. Eisenstadt (1956) sees the patron–client relationship as ‘ritualised personal relations’ and George Foster (1963) as ‘dyadic contract relationship’.

In the late 1970s, the patron–client relationship study was not active, and Jonathan Spencer (2007) calls the disappearance of the broker relations a ‘strange death of political anthropology’. Wolfgang Muno (2010) also claims that ‘clientelism lost its importance in the 1980s and 90s’. Joan Vincent reasons that there was a shift from persons, patron and brokers, to particular situations that allowed for new forms of relations and brokerage (1978: 186).

In 2011, Deborah James, from South Africa, argued that ‘Neoliberalism has increasingly problematised state-centred models of power and pushed for a reconceptualisation of the relationship between state and market. In this context, there was great potential for the return of brokers with neoliberal reform and economic and political deregulations; the broker appeared as an ideal anthropological informant’ (2011: 318). Muno (2010) brought the concept of the patron–client relationship and its dynamic back to the study of socio-anthropology by presenting a paper entitled ‘Conceptualising and Measuring Clientelism’.

2.3 Patron–Client Dynamic in Cambodia

At least four types of patron exist in Cambodia for Cambodian Christians: 1) Korean missionaries, 2) Western missionaries from Europe and North America, 3) FBOs, and 4) NGOs. Almost all patrons, except for a few local NGOs, are organisations from outside Cambodia because status and resource difference are essential for a patron–client relationship to form in Cambodia. However, for Cambodians, the patron is always an individual or an individual representing an organisation, connected through a personal relationship.

Also, from the Cambodians’ perspective, both Korean missionaries and Western missionaries have their benevolent patrons overseas. In 2008, American Protestant overseas missionaries raised $5.7 billion, which they distributed among 800 US agencies, and 47,261 US personnel served overseas in their mission projects (Weber, 2010: 166). However, many missionaries convinced themselves that their sponsors and churches back home are not like patrons of Cambodians. Paul De Neui argues that the Western missionaries view the relationship with their supporters as task-oriented and not necessarily persona...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Contents

- Acronyms

- Glossary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Patron–Client Relationship Issues

- 3. Aid Dependency Issues

- 4. Ted as Father and CBC Pastors as Children

- 5. Ted as FOB and CBC Pastors as Clients

- 6. Ted as Patron Partner

- 7. Conclusion

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Gap and Eul by Robert Oh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Ministry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.