eBook - ePub

America's Greatest Library

An Illustrated History of the Library of Congress

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Packed with fascinating facts, compelling images, and little-known nuggets of information, this new go-to illustrated guide to the history of the Library of Congress will appeal to history buffs and general readers alike. It distils over two hundred years of history into an engaging read that makes a Washington icon relevant today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access America's Greatest Library by John Y. Cole in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

FOR CONGRESS

1800-1897

Introduction

Books and libraries were essential to America’s founding generation. Most of the founders received vigorous, classical educations. It follows, then, that the members of the First Continental Congress, which convened in Philadelphia in 1774, were also avid readers. So were the first congressmen. When the early US Congresses met in New York and Philadelphia, the legislators were able to use both the New York Society Library and the Library Company of Philadelphia. But proposals to establish a library specifically for the use of Congress repeatedly met with failure. However, the 1790 agreement among Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and Thomas Jefferson to locate the permanent federal capital in the small town of Washington on the Potomac River—a location without libraries or bookstores—forced the government’s hand.

In 1800, as part of an act of Congress providing for the removal of the new national government from Philadelphia to Washington, President John Adams approved a $5,000 appropriation for the founding of a Library of Congress. A Joint Committee on the Library (Joint Library Committee) was formed to oversee the purchase of the books, furnish a catalog, and manage the institution. Thomas Jefferson’s presidency, from 1801 to 1809, gave the Library early prominence. During his term he approved a compromise act concerning the appointment of the Librarian of Congress, and the House of Representatives agreed to the Senate preference that the president of the United States appoint the Librarian. Jefferson named the first two Librarians of Congress, each of whom also served as the clerk of the House of Representatives.

It was also former President Jefferson, long retired from office, who came to the Library’s rescue during the War of 1812. In 1814, the British torched Washington, deliberately destroying the unfinished Capitol and the small congressional library in its north wing. To “replace the devastations of British Vandalism,” Jefferson wrote to his friend Samuel Smith, asking him to offer Congress Jefferson’s comprehensive collection of books because “there is in fact no subject to which a member of Congress may not have occasion to refer.” And Congress agreed. They purchased 6,487 books from Jefferson for $23,950.

Despite the attention of Jefferson and other politicians, the Library struggled for legitimacy. Was it intended to serve Congress alone, or to be the repository of knowledge for the entire country? Although it was created by a national legislature to serve the national government, the Library’s early decades were marked by uncertainty about its national role. Perennially underfunded, its primary function was to serve the Congress and, only secondarily, make popular literature accessible to the general public.

The Library played an important but limited role in assisting Congress in its work of making political decisions in the 1840s and 1850s. Its books and maps, for example, were especially useful for research and legislation, helping shape America’s westward expansion. The Library also was consulted on topics such as slavery, trade and tariffs, the European revolutions of 1848, and new and developing technologies. Senator James A. Pearce, who dominated the Joint Library Committee from the mid-1840s until the 1860s, was both protective of the Library and quite content with its limited role.

After the Civil War, the American economy improved rapidly, and both the federal government and the city of Washington expanded as well. The Library of Congress entered a period of unprecedented growth under the leadership of Ainsworth Rand Spofford, Librarian of Congress from 1864 to 1897. Spofford appealed to a growing cultural nationalism in pursuing his ambitious plan to turn the Library of Congress into a national library. In Jeffersonian terms, he advocated a single, comprehensive collection of American publications for use by both Congress and the American people. The centralization of copyright at the Library, achieved in 1870, was essential for the growth of these collections, as was the construction of a separate Library building. When the impressive new structure opened to the public across from the Capitol in 1897, Spofford called it “The Book Palace of the American People.”

6. In 1897, the Library moved from the US Capitol into its own building, a monumental structure immediately east of the Capitol. Today known as the Jefferson Building, it is a powerful and impressive symbol of both classical learning and American cultural nationalism. This photograph of the Great Hall’s second floor north corridor depicts an exuberant recognition of the Five Senses, the Eight Virtues, and six contemporary American publishing and printing firms.

7. John Adams, who in 1800 signed the first appropriation to provide books for the use of Congress.

1800

April 24 – President John Adams approves an “act to make provision for the removal and accommodation of the Government of the United States,” which establishes the Library of Congress. Five thousand dollars is appropriated “for the purchase of such books as may be necessary for the use of Congress” after it moves from Philadelphia to the new capital city of Washington. The books will be housed in the Capitol, and a Joint Library Committee will oversee the purchase of the books, furnish a catalog, and “devise and establish” the Library’s regulations.

1801

May 2 – The initial collection, consisting of 152 titles in 740 volumes and three maps, arrives and is stored in the office of the Secretary of the Senate.

1802

January 26 – President Thomas Jefferson approves a compromise act of Congress “concerning the Library for the use of both Houses of Congress.” The Librarian of Congress, who will be paid “two dollars per diem,” will be appointed by the President of the United States. The Joint Library Committee will supervise the expenditure of funds. Its rules and regulations will be established by the president of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives. “For the time being, its use is restricted to members of Congress and the President and Vice President of the United States.”

January 29 – President Jefferson appoints John J. Beckley, clerk of the House of Representatives and a political ally, to be the first Librarian of Congress.

April – The first Library catalog, Catalogue of the Books, Maps, and Charts Belonging to the Library of the Two Houses of Congress, is printed by William Dunne. It lists the collection of 964 volumes according to their size and appends a list of nine maps.

8. The Library of Congress looks to Thomas Jefferson as one of its principal founders. His concept of universality is the rationale for the comprehensive collecting policies of today’s Library of Congress.

“A Suitable Apartment”

— The Library’s First Home

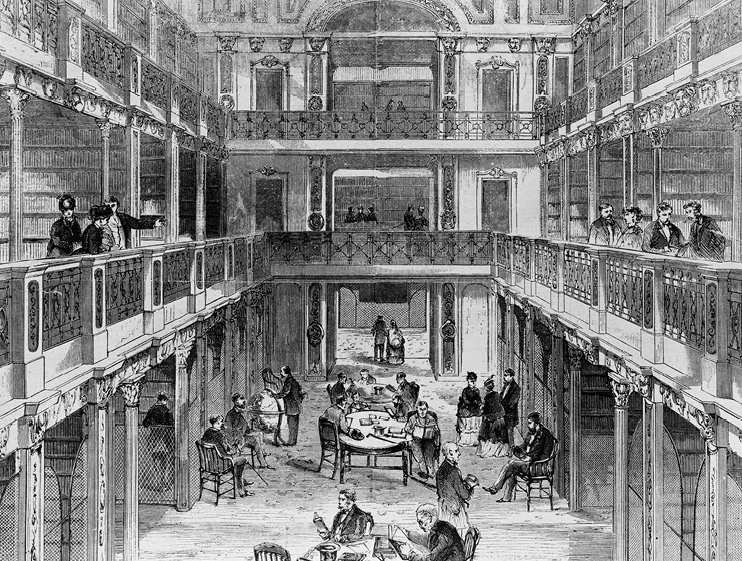

9. Following a disastrous accidental fire in 1851 that destroyed two-thirds of the Library’s collections, this elegant and enlarged new Library of Congress room was opened across the west...

Table of contents

- America’s Greatest Library

- Foreword

- Author’s Note and Acknowledgments

- PART ONE

- Introduction

- “A Suitable Apartment”— The Library’s First Home

- Comes the Flood: the Library and Copyright Deposit

- The Book Palace of the American People

- PART TWO

- Introduction

- Daniel Murray— A Collector’s Legacy

- Of Cards, Catalogs, and Computers

- Founding—and Lost—Documents

- From Annex to Adams

- PART THREE

- Introduction

- An Essential Resource in a Time of Grief

- “Knowledge Will forever Govern Ignorance”—The Madison Memorial

- The First Presidential Library

- The Library’s Pop Persona

- Appendix

- Further Reading

- Donor

- Image Credits