![]()

1

BEGINNINGS

It is 10 am on a Tuesday morning in Melbourne and a council cleaning crew is hard at work removing paint from a wall. In Fitzroy, the area where I live, a resident has found a swirl of calligraphy, the stylized letters that graffiti writers call a tag, on the front of their house. A phone call to the council sees the graffiti removal crew arrive with their high-pressure water hose and paint rollers. In a short while, the tag will disappear beneath a patch of fresh white paint. A few doors down, another resident has installed a surveillance camera to record the wall at the side of their house, which is frequently targeted by graffiti writers and street artists. The camera doesn’t seem to deter anyone; uncommissioned words and images continue to accumulate. In an adjacent street, graffiti writers working on an elaborate piece on the back of a fence are discovered by the police and cautioned.

Just around the corner, as it happens, there is an apartment complex called the Abito, whose ground-floor exterior is dominated by a mural of swirling tags washed in shades of red and green. The mural appears to have been added because this neighbourhood is saturated with graffiti and street art. The architects included the graffiti mural to ‘fit in with the graffiti on surrounding buildings’, to make the building blend in to the neighbour-hood, and perhaps hoped that the mural would shield it, as it were, from the attentions of other graffiti writers and street artists. Other buildings are a veritable scrapbook of pasted-on posters, painted tags, painted-out tags and street art murals; when the ‘graffiti mural’ of the Abito building is tagged, or attracts comments such as ‘Keep Fitzroy Gangster’, these unauthorized additions are promptly removed. Not far away, the facade of another apartment complex building reads ‘HIVE’. The word has been sculpted in concrete into three-dimensional ‘wild style’ graffiti lettering. In a nearby street, another building has been designed by the same architects, ITN. Called the End to End building, it features three graffiti-covered train carriages on the building roof.

Hive Graffiti Apartments, Carlton, Melbourne.

End to End building, Collingwood, Melbourne.

This area of Melbourne is an ideal place to start exploring some of the contradictions around graffiti and street art in contemporary urban life. Some residents are annoyed when they find a tag or stencil on their wall, considering it a nuisance that can be managed by a phone call to the council. Others react with fear or rage; they install a surveillance camera or call the police. Some residents take photographs of graffiti and street art, post them online and share them with friends. And then there are those who find inspiration in graffiti and street art as an aesthetic. They see it as embellishing the look of a building, enhancing the pleasures of the neighbourhood, adding a moment of delight to the daily walk to work. Far from disliking its aesthetic, some architects, like Zvi Belling of ITN, have incorporated it into their designs. Whether feared or loved, graffiti and street art have become absorbed into the very streetscape of the area. As put by Kim Dovey, Simon Wollan and Ian Woodcock, researchers in architecture and urban design, graffiti has become part of Fitzroy’s very character.

Such contradictions can be found in cities across the world. In London, graffiti writers have been sentenced to lengthy periods of imprisonment: Noir of the Addicted to Steel crew was sentenced to sixteen months’ imprisonment, and the prolific tagger Vamp to three and a half years. Yet, as part of its ‘Street Art’ exhibition in 2008, the Tate Modern included a tent with a whiteboard for people to tag. Many artists become interested in street art as a means of reclaiming public space from the glut of advertising billboards that cover city spaces; yet they later find themselves employed, as in New York, to hand-paint advertisements onto walls. The municipal removal of unauthorized street art and graffiti is taken for granted, but in Melbourne, when one particular stencil was painted over by a cleaning crew, the city’s deputy mayor apologized for the mistake – because the stencil was by Banksy, probably the most famous street artist in the world. His Melbourne stencils are now regarded as rare traces of his visit to the city in 2003.

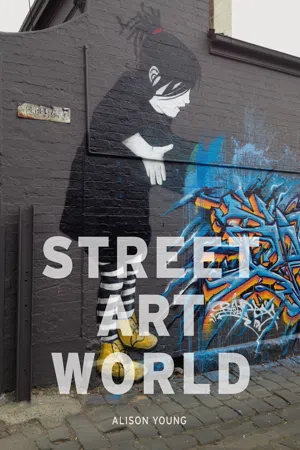

This book engages with the contradictions and contestations around street art and graffiti, and looks at how they play out in cities around the world. It is about how street art has radically transformed city spaces and become a familiar part of the character of urban life itself – how street art and graffiti have become images that we live by. In recent years, street art has been exhibited in major museums, sold for six-figure sums in auction houses, drilled out of walls by avid collectors and endlessly discussed at art festivals around the world. Fifteen years ago, none of this was imaginable; even ten years ago, street art had only just touched the fringes of mainstream culture. What has happened in the last decade to make street art, though still illegal, so familiar?

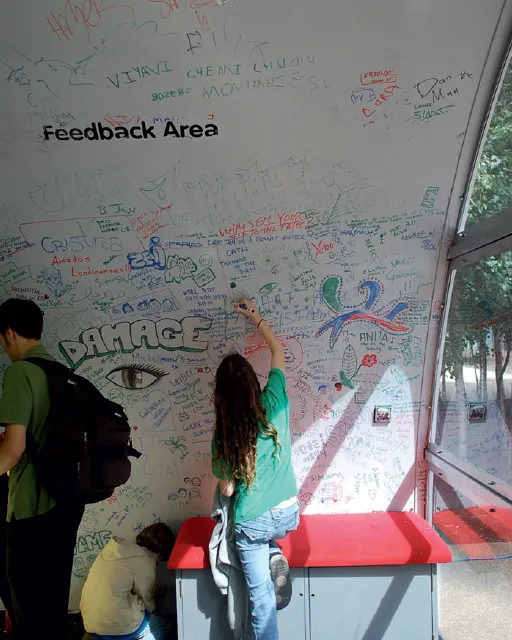

Tag board, ‘Street Art’ exhibition, Tate Modern, London, 2008.

To answer these questions, we need to begin by considering street art’s origins. When and where did it emerge? Did it develop out of graffiti or is it a different cultural practice? If it is a transformation of graffiti, then when did graffiti begin? It is impossible to show that one develops straight out of the other because the developmental timelines are interconnected. The divide between the two communities is not as stark as it might sometimes seem, or is often claimed, even though there exists real antagonism between them. Graffiti writers sometimes become street artists and street artists sometimes become graffiti writers. They also trade techniques: graffiti writers might use stencils and street artists have sometimes included wild style calligraphy in their work. The histories of graffiti and street art are both entwined and oppositional and, as will become clear, any attempt to identify a moment of shared beginning or a linear progression is likely to be frustrated.

Graffiti and street art both tend to involve the application of paint to urban surfaces. Beyond this, however, they are quite different cultural practices. Graffiti is often compared to calligraphy and, like calligraphy, involves writing letters in various unified styles. The graffiti writer usually chooses to write their graffiti name, or ‘tag’, which can be done with marker pens, aerosol cans, paint rollers and even fire extinguishers. A tag can easily become what is called a ‘throw-up’, involving rapidly written ‘bubble’ letters drawn quickly on a wall, or a ‘piece’, a larger, mural-like design utilizing multiple colours and complex techniques. Although tags are easily and often dismissed in the mainstream media as scribble or scrawl, an elegantly executed tag, especially when repeated across a surface, can have great visual appeal. A recent innovation is the use of a high-pressure hose to remove dirt, paint or other layers from a surface to create a ‘reverse’ tag. Lasers have also been used to project tags onto buildings. Some have even written their tag in three dimensions, carving letters into metal or concrete, which can then be bolted onto a wall.

Tag by Pilfer, Tokyo, 2014.

Throw-up by Reka, Melbourne, 2014.

Piece by Reas New York, 2000.

Tags by Retna New York, 2014.

Piece by Deams, Melbourne, 2014.

Metal tag by Revs, Bushwick, New York, 2011.

While graffiti writers remain largely focused on letters and words as the primary content of their representations, street art has no such limit as to content. Street artists use paint, paper, sculptural objects and manipulate the built environment; they might incorporate live performance, video and sound into their artworks. Images may be hand-drawn, painted, stencilled, printed or glued onto walls; images can be very large or deliberately minuscule, rewarding those who direct their gaze down at the lower parts of walls or upwards.

Some street artists place their work in public places in order to replace or alter advertising. They select billboards or the panels used for adverts at bus stops as the locations for their work. Some, like Vermibus in Berlin, Brandalism in the United Kingdom and the Public Ad Campaign in New York, use keys to unlock these panels, remove the advertising poster and replace it with an artwork. Jordan Seiler began by making artworks that he pasted over advertising billboards in New York’s subway stations but more recently has developed a smartphone app, NO AD, which, once downloaded, allows a user to look through their smartphone app at an artwork instead of an advertisement.

Paste-up by Pablo Delgado, Hackney, London, 2013.

Street sculpture by Cityzen Kane, London, 2011.

Bus shelter with advertisements, Knightsbridge, London, 2015.

Bus shelter after alteration by Vermibus, Knightsbridge, London, 2015.

Stickers by Goon Hugs, Melbourne, 2014.

‘Adbusters’ or ‘subvertisers’ like Vermibus and Brandalism select locations for their work in order to criticize consumerist society and the monetizing of public space. Sometimes placement of artwork is determined by the nature of the artwork: stickers, also known as ‘slaps’, can only be placed on surfaces to which their glue will adhere, such as metal posts or doors. Stickering is a practice carried out by both graffiti writers and street artists. Some design and draw stickers by hand; others have them made professionally. The aim may be to place a sticker in a single well-chosen spot, so that it functions as a tiny artwork, or it may be to put up as many stickers in as many locations as possible all over the city, in a manner akin to ‘bombing’ the city with tags. The Melbourne artist Goon Hugs does both, handwriting some stickers which are left in judiciously selected locations, but at other times printing large quantities of stickers for pasting in mass numbers in confined areas such as doorways or for entirely covering a wall.

Street artists often reference graffiti culture in their work, and some openly acknowledge that they started out as taggers. The celebrated ‘Art in the Streets’ exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles in 2011 contained as many graffiti writers as it did street artists. On the whole, however, the relationship between the two communities is contested and uncomfortable, with some street art pieces being painted over by graffiti writers (in a perhaps unintended echo of the much-hated buffing of graffiti by municipal authorities). The most notorious conflict between street art and graffiti was the dispute between Banksy and King Robbo, a famed London-based graffiti writer. The origins of their conflict are unclear but it seems that a private disagreement spilled into public space when Banksy painted over most of one of the last surviving King Robbo pieces in London. The two then began a kind of contest where each would hijack pieces by the other by altering or adding words and symbols; these could often be read as implying that the author of the original piece lacked talent. Banksy altered a King Robbo piece by adding the letters F-U-C as a prefix; one Banksy piece of a hitchhiker whose sign stated ‘Anywhere’ was altered to read ‘going nowhere’; and a famous Banksy piece showing a little boy fishing in the polluted Regents Canal at Camden received the annotation ‘Banksy, by being in London your [sic] depriving your village of its idiot’. (After King Robbo suffered what woul...