- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

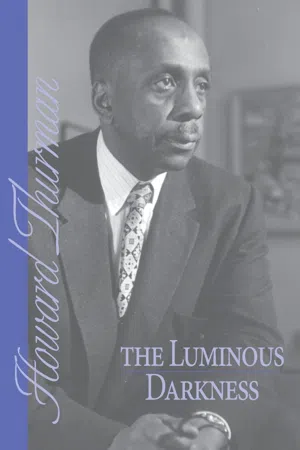

The Luminous Darkness

About this book

The Luminous Darkness is a commentary on what segregation does to the human soul. First published in the 1960s, Howard Thruman's insights apply today as we still try to heal the wound of those days. Thurmna bares the evil of segregation and points to the ground of hope which an bring all humanity together.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Religion•

ONE OF THE CENTRAL PROBLEMS IN HUMAN relations is applying the ethic of respect for personality in a way that is not governed by special categories. The question keeps intruding, "Does the category by which life is defined decree how the ethic shall be applied?" For instance, if a man is committed to a reverent view of life, does he rule out high regard for life that threatens or seems dangerous to him? If a particular man, by definition, is not human, then may not the ethical behavior that usually applies be suspended? Does a man tend to become immoral and irreligious as his security is threatened?

It is part of the wisdom of the Judaeo-Christian ethic that all men are enjoined to love God and to love one another. However ardently a man may hold to this attitude, his commitment is nevertheless threatened by the reality that he still will admit categories of exception and extenuating circumstances which amend and sometimes nullify his respect for human life.

During World War II I lived in California. It was not infrequent that one saw billboard caricatures of the Japanese: grotesque faces, huge buck teeth, large dark-rimmed thick-lensed eyeglasses. The point was, in effect, to read the Japanese out of the human race; they were construed as monsters and as such stood in immediate candidacy for destruction. They were so defined as to be placed in a category to which ordinary decent behavior did not apply. Without any apparent wrench of conscience or violation of due process, it was possible for the entire Japanese-American community to be removed from the West Coast and placed in relocation camps in the center of the country. It was open season for their potential extermination, thus providing immunity from guilt feelings. During World War I the same behavior was directed toward the Germans and people of German descent. Many churches and ministers joined in the practice. I have a friend who was so deeply injured by her experiences of this behavior during the war that she still cannot bring herself to attend Christian religious services of any kind. So conditioned was she that during World War II she lived in muted terror which expressed itself in the kind of alarm she showed whenever her doorbell rang in the early morning or in the late evening.

This, in broad outline, indicates the moral climate in which Negroes and white persons have lived in the United States. The Christian ethic has been deeply influenced by this circumstance. For a long time the Christian Church has profoundly compromised with the demands of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, especially with respect to the meaning and practice of love.

When I was a boy growing up in Florida, it never occurred to me, nor was I taught either at home or in church, to regard white persons as falling within the scope of the magnetic field of my morality. To all white persons, the category of exception applied. I did not regard them as involved in my religious reference. They were not read out of the human race—they simply did not belong to it in the first place. Behavior toward them was amoral. They were not hated particularly; they were not essentially despised; they were simply out of bounds. It is very difficult to put into words what was at work here. They were tolerated as a vital part of the environment, but they did not count in. They were in a world apart, in another universe of discourse. To lie to them or to deceive them had no moral relevancy; no Category of guilt was involved in my behavior. There was fear of their power over my life; the meaning and the basis of this fear will be discussed at another point in my essay.

What was true for me as a boy was true also of any little white boy in my town with an important and crucial difference! The structure of the society was such that I was always at his mercy. He was guaranteed by his society; I was not. I was always available as an outlet for his hostility whatever may have been the cause of his hostility. If he was angry because he had been chastised by his parents or because of something else that had happened to him in his world and he met me on the street, he could easily give vent to his anger. He could molest me or push me off the sidewalk without too great a danger of retaliation. Or if he was just out for “kicks” he could do the same thing and most often be protected by his group. Thus I was taught to keep out of his way, to reduce my exposure to him under any and all circumstances. I lived in a segregated world into which he could come and go at will; but into his world I could go only when directed or on business. His behavior tended to be unpredictable and irresponsible, therefore in no sense binding upon him. I was frozen in my status; he was fluid in his.

Precisely what does it mean to be frozen in one’s status? The issue is not one of law or legality as expressed in statutes. These are after the fact. There is something deeper at work. That it was a violation of the law of the state and the ordinances of my town for me to enter the public library as a patron or to borrow a book was not the immediately prohibiting element. It was taken for granted that the very existence of law was for the protection and the security of white society. The frozen status was a way of living; it was a part of the common life. It was to function without any collective consensus of security. Always and everywhere you were strictly on your own and your life depended upon the survival techniques you had learned in the living.

As I look back upon those days, I never gave to the way of living demanded of me by my environment, the inner sanction of my spirit. I gave to it what may be called the sanction of strategy. There was a place in me untouched by these pressures on my life. At the same time I was not consciously involved in deep inner conflict, since the sensitive area of my own ethics had not been implicated in the issues of my life of segregation. The tragedy was that no ethical judgment prevailed. Living in a frozen status established the boundaries of my moral concern. Those who were a part of my segregated world came under the judgment of my interpretation of the meaning of religion. It made for a peculiar kind of self-righteousness. The common saying in my world was: the white man did not have any religion. By implication we did. That kept me from expecting him to act toward me as I would expect a fellow Christian to act, but curiously enough my religion did not demand of me that I act toward him as a Christian should act. At the risk of being repetitious, he was not regarded as worthy of a Christian response. It was a cruel dilemma; the price paid for a kind of inner balance that would make for some measure of peace of mind was the rigid narrowing or restricting of the Christian ethic. The struggle was to try to achieve a sense of self in a total environment that threatened the self.

•

It is clear that for the Negro the fundamental issue involved in the experience of segregation is the attack that it makes on his dignity and integrity. We become persons by an other-than-self reference which is other persons. We become human in a human situation. The primary group with which this process is immediately associated is the family. The sense of being deeply cared for and protected and loved in the immediate family provides the firm ground of security for the self. The mother and the father of the child, the adult, prestigious members of the family and intimates—these are the points of reference for the child.

It is difficult to assess what happens to the child in an environment where he sees his parents and other adults humiliated and reduced to insignificance by the treatment received from certain white persons in the general environment. To experience their defenselessness and at the same time to regard them as his defenders is cruel and rottening to the self. Always a way has had to be found for handling this contradiction.

Segregation gives rise to an immoral exercise of power of the strong over the weak, that is to say, advantage over disadvantage. The restrictions affecting the disadvantaged, the Negroes, are mandatory, while there is a voluntary element in the way the same restrictions affect white persons. Segregation has a margin of freedom of movement without threat, always available to the powerful but not available to the weak. In the old days on the Jim Crow trains in the South, the white conductor used double seats in the Negro section of a car as his office. Often that would leave only six other seats for Negro passengers. If the seats were taken when you got on the train, you stood up to the end of your journey, regardless of the many vacant seats in the white coach. If you tried to sit in the conductor’s seats, he would usually get the Negro porter to move you. Rarely would he himself become directly involved in any conversation with Negro passengers.

In American society generally, formal power rests largely within the white community. In white society is the citadel of the so-called power structure. The controls that determine the establishment and maintenance of law and order reside there. For this reason, prestigious members of the group can and often do function without social and moral responsibility. Segregation is at once one of the most blatant forms of moral irresponsibility. The segregated persons are out of bounds, are outside the magnetic field of ethical concern. It is always open season. The reason has been previously discussed. This was the general climate and the Christian ethic made no impact. Of course the radical difference between the position of Negroes and white persons as regards the effect of social irresponsibility was the difference in power. The idea that a Negro interpreted the white person as being out of bounds had a limited scope in which to operate because of the strictures under which he was forced to live. The power of the white person tended to take all integrity out of his personal relations with Negroes, but it did not affect him materially in his function in the world in which he had established controls. In short, he was less vulnerable than the Negro because he was a white man.

On the other hand, his power gave him a wide range of opportunities to affect the life of Negroes without responsibility. He could even damage his person with immunity. To illustrate how deeply involved is the issue here: When I was a boy I earned money in the fall of the year by raking leaves in the yard of a white family. I did this in the afternoon, after school. In this family there was a little girl about six or seven years old. She delighted in following me around the yard as I worked. One of her insistences was to scatter the piles of leaves in order to find a particular shape to show me. Each time it meant that I had to do my raking all over again. Despite my urging she refused to stop what she was doing. Finally I told her that I would report her to her father when he came home. This was a real threat to her because she stood in great fear of her father. She stopped, looked at me in anger, took a straight pin out of her pinafore, ran up to me and stuck me with the pin on the back of my hand. I pulled back my hand and exclaimed, "Ouch! Have you lost your mind?” Where-upon she said in utter astonishment, "That did not hurt you—you can’t feel."

In other words, I was not human, nor was I even a creature capable of feeling pain. Manifestly this is an extreme position, but it indicates the social and psychological climate in which it would be possible for a little girl to grow up in a Christian family with such a spontaneous attitude toward other human beings. Segregation guarantees such inhumaneness and throws wide the door for a complete range of socially irresponsible behavior. This obtains for the segregated and the separated; for under the system white persons are separated from Negroes but they are not segregated—only the Negroes are segregated. There can be shuttling back and forth between the two worlds by the separated but not so for the segregated.

The fact that the status of the Negro in a segregated society is frozen does not mean that he is without a special kind of power. In order to keep his status frozen, many things must be done within the white society which limit its development and hamper its enrichment. When a new law for the common good is being considered, before the merits of the law itself can be examined, there is a previous consideration that must be taken into account: what bearing will the new law have on the relationship between whites and Negroes? A way must always be found that will provide maximum benefit to the white community and minimum benefit to the Negro community. The touchstone is not to disturb the fixed status while at the same time to develop increased freedom for growth and development within the white community. How much improvement can be given to the schools for white children without providing a similar improvement to the schools for Negro children? How much improvement can be made in city streets and lighting without improving streets in the Negro community? If there is a county or state fair, what can be done so as to exclude Negroes or include them as insignificantly as possible? Can white society function as if Negroes did not exist, or if their existence is acknowledged, can this be done so as not to encourage their getting out of their place?

•

But any society is apt to be so viable that things are always shifting and are constantly being influenced by the larger community of the country and the world. The blame for unwelcome change can easily be ascribed to the influence or activity of the outsider. The common cry in the South is that everything was moving along quite peacefully until the agitator from the outside interfered. The notion that segregated persons would ever of themselves on their own volition want conditions to change is impossible to entertain. And the reason is not far to seek, for if it were ever admitted, then the whole structure of the relationship would be brought into question. This would create an intolerable situation. From the point of view of power, the stability of the order rests upon its total acceptance. To this end, the ancient role of the scapegoat is called into play. The mind of the South is temporarily incapable of dealing with dissatisfied and hostile restless Negroes. To admit this reality is to destroy the myth; to destroy the myth is to have all landmarks shift, making it impossible to hold one’s course and keep one’s bearings. Hence every effort has to be made to keep out the outsider and at the same time to open the way for the out-sider to enter that he may be available to bear the brunt of the cause for unrest.

If the physical presence of the outsider is not available, then his influence may be blamed. Such influence flows into the common life because of the mobility of the segregated ones which may take them into other regions where the pattern is more fluid than in the South, or because of the enchantment with organizations that are based outside the region. It is not an accident that the attempt was made in Alabama, for instance, to declare an organization like the NAACP illegal in the state, or to label all the unrest and dissatisfaction as Communist inspired. It is this notion which, in part, accounts for the fact that again and again some white persons from other regions who settle in the South find themselves being more intensely anti-Negro than the native Southern white. If they are to share the common life, they must become a part of it so as not to seem to be outsiders and therefore a threat to the pattern. This is absolutely mandatory if one’s livelihood is dependent upon harmonious relations with the people of the community. A way has to be found to blend with the landscape and become accepted if one is to survive.

Another device for dealing with the issue of unrest within the Negro community deep within the segregated pattern is to classify the white person as a "Nigger lover." In St. Augustine, Florida, during the turbulence of 1963, a newer phrase was used to apply to white persons who had rejected the pattern: "white Niggers." There the identification was complete and provision in the title made for the difference in skin coloring. The point here is that there is little ability to handle the fact that Negroes are rejecting the patterns upon which the social stability of the region rests. The rejection has to be rationalized so as to make the situation tolerable. Meanwhile, every measure must be taken to restore the orderly way. The use of electric cattle prods, the turning of the full driving stream of water for fighting fires upon little children, defenseless girls, the dynamiting of a church resulting in the violent death of little children, the ambushing of men in cold blood, the brutalizing of vulnerable women in the stark desolation of jail cells—these are deeds of men with their backs against the wall; they are at war. And the stakes: the established pattern that is fading away. There is no preparation in mind or heart or culture for relating to Negroes outside of the segregated pattern.

Within this pattern, as has been suggested, it is possible for a white person to have some freedom of movement. He can make excursions beyond the barriers with real immunity. In my home town, white persons attended religious services in our church—but no Negro could attend services in a white church. One year I pumped the pipe organ for the organist to practice on at the Episcopal church. But on Sunday, at the service of worship, only a white boy could do this chore.

To be sure, when white persons attended our services, they were well-behaved, but they were present. I remember one Sunday some young people out on a lark came to our services. One of the fellows was not properly dressed. When the deacons tried to keep him from entering, he pushed his way into the service and we were all helpless to eject him because of the fear of reprisals. The following week he died suddenly from a heart attack and the word ran through the whole town that he was dead as an act of God.

Until very recently, then, the white person had certain large prerogatives which permitted him to disregard segregation or to honor it. More accurately, he was always under obligation to honor the pattern, but as a point of power privilege, he could disregard it on occasion. That is the essential point to understand. In this matter he has enjoyed a unique privilege. He could move in and out of the Negro world without any major threat to the pattern.

•

The crisis set in motion by the Supreme Court Decision of 1954 introduced a radically new situation. To dishonor segregation has been pre-empted by Negroes as a right, not as a whim or a private prerogative. This decision, more than any other which the Court has rendered in the area of Civil Rights, created an entirely new issue for the South particularly. Why? Because it declared segregation itself to be unconstitutional. It made its declaration concerning the most critical seedbed for the perpetuation of the Southern pattern: the tax-supported public schools. It dealt with the fundamental responsibility of a society to educate the young, who in turn would become the responsible adults of the future. This is the taproot of the society and here it was declared that all children must be free to learn to live together with easy access to one another while the mind is developing and the heritage of the culture is being transmitted. The instinct to reject the decision sprang out of the profound awareness that it sounded the death gong for the pattern of segregation in all of its far-flung and complex dimensions.

The decision created a particularly traumatic experience for the man of good will in the white South. I mean the man who had a basic humanitarianism and who wanted the Negro to get the maximum fulfillment he could within the structure of the pattern. Such a person would be in favor of, and often would work for, improvement of the schools, decent buildings, and adequate salaries for Negro teachers. He would give of his time and money in working to improve race relations. The period following hard upon the clo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Prologue

- Foreword

- The Luminous Darkness

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Luminous Darkness by Howard Thurman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.