eBook - ePub

Think Like a Mathematician

Get to Grips with the Language of Numbers and Patterns

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Was mathematics invented or discovered? Why do we have negative numbers? How much math does a pineapple know? Think Like a Mathematician will answer all your burning questions about mathematics, as well as some ones you never thought of asking! Whether you want to know about probability, infinity, or even the possibility of alien life, this book provides a fun and accessible approach to understanding all things mathematics - and more - in the context of everyday life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Think Like a Mathematician by Anne Rooney in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Mathematics & History & Philosophy of Mathematics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

You couldn’t make it up – or did we?

Is mathematics just ‘out there’, waiting to be discovered? Or have we made it up entirely?

Whether mathematics is discovered or invented has been debated since the time of the Greek philosopher Pythagoras, in the 5th century BC.

Two positions – if you believe in ‘two’

The first position states that all the laws of mathematics, all the equations we use to describe and predict phenomena, exist independently of human intellect. This means that a triangle is an independent entity and its angles actually do add up to 180°. Mathematics would exist even if humans had never come along, and will continue to exist long after we have gone. The Italian mathematician and astronomer Galileo shared this view, that mathematics is ‘true’.

‘Mathematics is the language in which God has written the universe.’

Galileo Galilei

It’s there, but we can’t quite see it

The Ancient Greek philosopher and mathematician Plato proposed in the early 4th century BC that everything we experience through our senses is an imperfect copy of a theoretical ideal. This means every dog, every tree, every act of charity, is a slightly shabby or limited version of the ideal, ‘essential’ dog, tree or act of charity. As humans, we can’t see the ideals – which Plato called ‘forms’ – but only the examples that we encounter in everyday ‘reality’. The world around us is ever-changing and flawed, but the realm of forms is perfect and unchanging. Mathematics, according to Plato, inhabits the realm of forms.

Although we can’t see the world of forms directly, we can approach it through reason. Plato likened the reality we experience to the shadows cast on the wall of a cave by figures passing in front of a fire.

If you are in the cave, facing the wall (chained up so that you can’t turn around, in Plato’s scenario) the shadows are all you know, so you consider them to be reality. But in fact reality is represented by the figures near the fire and the shadows are a poor substitute. Plato considered mathematics to be part of eternal truth. Mathematical rules are ‘out there’ and can be discovered through reason. They regulate the universe, and our understanding of the universe relies on discovering them.

What if we made it up?

The other main position is that mathematics is the manifestation of our own attempts to understand and describe the world we see around us. In this view, the convention that the angles of a triangle add up to 180° is just that – a convention, like black shoes being considered more formal than mauve shoes. It is a convention because we defined the triangle, we defined the degree (and the idea of the degree), and we probably made up ‘180’, too.

At least if mathematics is made up, there’s less potential to be wrong. Just as we can’t say that ‘tree’ is the wrong word for a tree, we couldn’t say that made-up mathematics is wrong – though bad mathematics might not be up to the job.

‘God created the integers. All the rest is the work of Man.’

Leopold Kronecker (1823–91)

Alien mathematics

Are we the only intelligent beings in the universe? Let’s assume not, at least for a moment (see Chapter 18).

If mathematics is discovered, any aliens of a mathematical bent will discover the same mathematics that we use, which will make communication with them feasible. They might express it differently – using a different number base, for example (see Chapter 4) – but their mathematical system will describe the same rules as ours.

If we make up mathematics, there is no reason at all why any alien intelligence should come up with the same mathematics. Indeed, it would be rather a surprise if they did – perhaps as much of a surprise as if they turned out to speak Chinese, or Akkadian, or killer whale.

For if mathematics is simply a code we use to help us describe and work with the reality we observe, it is similar to language. There is nothing that makes the word ‘tree’ a true signifier for the object that is a tree. Aliens will have a different word for ‘tree’ when they see one. If there is nothing ‘true’ about the elliptical orbit of a planet, or about the mathematics of rocket science, an alien intelligence will probably have seen and described phenomena in very different terms.

How amazing!

Perhaps it is amazing that mathematics is such a good fit for the world around us – or perhaps it is inevitable. The ‘it’s amazing’ argument doesn’t really support either view. If we invented mathematics, we would create something that adequately describes the world around us. If we discovered mathematics, it would obviously be appropriate to the world around us as it would be ‘right’ in a way that is larger than us. Mathematics is ‘so admirably appropriate to the objects of reality’ either because it’s true or because that’s what it was designed for.

How can it be that mathematics, being after all a product of human thought which is independent of experience, is so admirably appropriate to the objects of reality?’

Albert Einstein (1879–1955)

Look out – it’s behind you!

Another possibility is that mathematics seems astonishingly good at representing the real world because we only look at the bits that work. It’s rather like seeing coincidences as evidence of something supernatural going on. Yes, it’s really amazing that you went abroad on holiday to an obscure village in Indonesia and bumped into a friend – but only because you are not thinking about all the times you and other people have gone somewhere and not bumped into anyone you knew. We only remark on the remarkable; unremarkable events go unnoticed. In the same way, no one thinks to fault mathematics because it can’t describe the structure of dreams. So it would be reasonable to collate a list of areas where mathematics fails if we want to assess its level of success.

‘The unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics’

If mathematics is made up, how can we explain the fact that some mathematics, developed without reference to real-world applications, has been found to account for real phenomena often decades or centuries after its formulation?

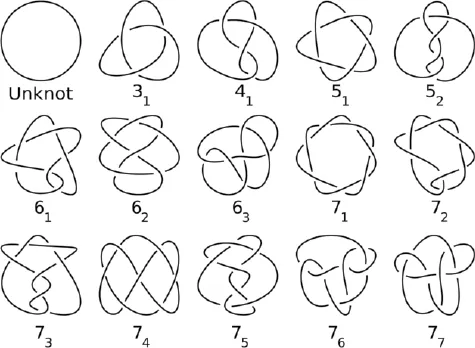

As the Hungarian-American mathematician Eugene Wigner pointed out in 1960, there are many examples of mathematics developed for one purpose – or for no purpose – that have later been found to describe features of the natural world with great accuracy. One example is knot theory. Mathematical knot theory involves the study of complex knot shapes in which the two ends are connected. It was developed in the 1770s, yet is now used to explain how the strands of DNA (the material of inheritance) unzip themselves to duplicate. There are still counter-arguments. We only see what we look for. We choose the things to explain, and choose those that can be explained with the tools we have.

Perhaps evolution has primed us to think mathematically and we can’t help doing so.

Knot theory: the simplest possible true knot is the trefoil or overhand knot, in which the string crosses three times (31 below). There are no knots with fewer crossings. The number of knots increases rapidly thereafter.

‘How do we know that, if we made a theory which focuses its attention on phenomena we disregard and disregards some of the phenomena now commanding our attention, that we could not build another theory which has little in common with the present one but which, nevertheless, explains just as many phenomena as the present theory?’

Reinhard Werner (b.1954)

Does it matter?

If you are just working out your household accounts or checking a restaurant bill, it doesn’t much matter whether mathematics is discovered or invented. We operate within a consistent mathematical system – and it works. So we can, in effect, ‘keep calm and carry on calculating’.

For pure mathematicians, the question is of philosophical rather than practical interest: are they dealing with the greatest mysteries that define the fabric of the universe? Or are they playing a game with a kind of language, trying to write the most elegant and eloquent poems that might describe the universe?

‘The miracle of the appropriateness of the lan...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Contents

- Introduction: What is mathematics, really?

- Chapter 1: You couldn’t make it up – or did we?

- Chapter 2: Why do we have numbers at all?

- Chapter 3: How far can you go?

- Chapter 4: How many is 10?

- Chapter 5: Why are simple questions so hard to answer?

- Chapter 6: What did the Babylonians ever do for us?

- Chapter 7: Are some numbers too large?

- Chapter 8: What use is infinity?

- Chapter 9: Are statistics lies, damned lies or worse?

- Chapter 10: Is that significant?.

- Chapter 11: How big is a planet?

- Chapter 12: How straight is a line?

- Chapter 13: Do you like the wallpaper?

- Chapter 14: What’s normal?

- Chapter 15: How long is a piece of string?

- Chapter 16: How right is your answer?

- Chapter 17: Are we all going to die?

- Chapter 18: Where are the aliens?

- Chapter 19: What’s special about prime numbers?

- Chapter 20: What are the chances?

- Chapter 21: When’s your birthday?

- Chapter 22: Is it a risk worth taking?

- Chapter 23: How much mathematics does nature know?

- Chapter 24: Is there a perfect shape?

- Chapter 25: Are the numbers getting out of hand?

- Chapter 26: How much have you drunk?

- Copyright