- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Think Like a Psychologist is a fun introduction to the universal aspects of psychology that affect our daily lives and relationships.

Using a Q&A format, the book delves into questions such as: • What goes on in your children's minds during adolescence?

• Why do many of us feel dissatisfied?

• Is it possible to improve your memory?

• Can you control your dreams?An accessible read that helps to explain exactly what's going on in the world around us.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Think Like a Psychologist by Anne Rooney in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Movements in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

What can we learn from a brain?

We can’t watch the brain working, so how do we know what it does?

Psychology is the study of what goes on in the brain – thinking, learning, personality, dreams, desires, character formation, behaviour determination, and disorders of all of those. But unlike the study of what goes on in, say, the heart, there is no mechanical process to observe directly. So scientists have had to find some ingenious ways of monitoring our thought processes.

Viewing our thoughts

In the early days of psychology, the only way of looking at a brain directly was once its owner had died. All psychological study had to be through experimenting with, observing and questioning live brain-users. While all those techniques remain extremely useful today, we now have ways of viewing the living brain while it’s doing its stuff. But viewing the brain raises as many questions as it answers. Knowing about the biology of the brain only takes us so far. We can see it is doing something, but we still can’t see quite what it is, or how it is doing it. We can see neurons firing as someone thinks, but we can’t see what they are thinking, or why they had that thought, or how they will remember (or forget) it.

SIZE MATTERS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Animal | Neurons | Animal | Neurons |

Fruit fly | 100,000 | Cockroach | 1,000,000 |

Mouse | 75,000,000 | Cat | 1,000,000,000 |

Baboon | 14,000,000,000 | Human | 86,000,000,000 |

What goes where?

For millennia, the only way to discover which parts of the brain were used for different functions was to observe people who had suffered head injuries and note how this had affected their mental or physical abilities, mood or behaviour. The changes were a good indication that different parts of the brain were responsible for different functions (emotions, cognition, personality and so on). Post-mortem examination revealed brain damage that might have been related to changes or impaired function that had been noticed in the person when they were alive. To acquire meaningful insights into the workings of the brain, scientists needed lots of brains to examine, and sophisticated scientific equipment to do it with. So the brain was pretty much a closed book until the 20th century. It’s not a very open book, even now.

NEUROSCIENCE – THE BASICS

The brain is made up of lots of neurons (nerve cells), which are responsible for producing neural activity. ‘Lots’ is around 86 billion. Neural activity includes receiving ‘messages’ from the receptors in the sensory organs located in different parts of the body and transmitting messages to activate the muscles, for example, in other parts of the body. Some actions, such as raising your arm, are conscious; others, such as an increased heartbeat, are unconscious.

Different parts of the brain are responsible for different types of neural activity. Information from the eyes is transmitted to the visual cortex at the back of the brain and processed to produce the images we ‘see’ in the mind. Emotions, on the other hand, are processed in the amygdalae, two small structures located deep within the brain.

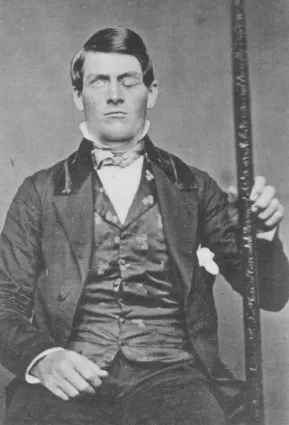

The unfortunate Phineas Gage

The idea that specific parts of the brain might be responsible for different functions originated with the medical case of a railroad construction foreman called Phineas Gage. On 13 September 1848, Gage was seriously injured when a metal tamping iron, a long, pointed rod weighing six kilograms, was accidentally fired through his head. It entered through the cheek and left through the top of his head, taking fragments of his brain with it. He lost a bit more brain when he vomited, and ‘about half a teacup full’ of brain fell on the floor, according to the doctor who attended him. The main damage was to one of the frontal lobes of his brain.

Although his friends had a coffin ready and waiting for him, remarkably, Gage lived. But his personality changed considerably for a long period. Instead of the polite, friendly man he had been before the accident, he became difficult and antisocial (though not the terrible character that legend suggests). His social ineptitude lessened with time, and he ended his days working as a stagecoach driver in Chile. It’s possible that the routine of his new life helped in his rehabilitation, as structured activity is found to be helpful in the treatment of many patients suffering damage to the frontal lobes.

Phineas Gage

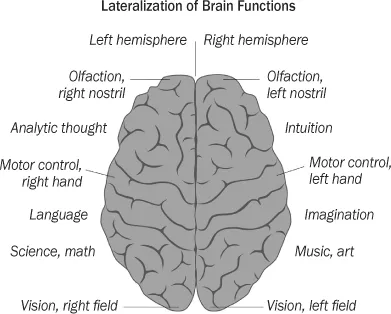

In two minds

The brain comprises two halves, or hemispheres. Each hemisphere contains the same structures and there is communication between the two via a thick bundle of nerve fibres called the corpus callosum.

How the two hemispheres work together was explained by Roger W. Sperry, a neuropsychologist who used the technique of severing the corpus callosum to treat patients with severe epilepsy. It sounds drastic, and it was, but it did cure the epilepsy. After he had cut the connection between the two hemispheres, the right hand literally did not know what the left hand was doing.

At first the surgery appeared to have little impact on the patients – apart from relieving their epilepsy. But investigation of Sperry’s split-brain patients soon revealed that there had been other major changes. In the process, Sperry gained new insights into how the two halves of the brain normally work together.

Sperry found that if he presented a picture to the right visual field (processed by the left side of the brain), the patient could name the object in speech or writing, but if it was presented to the left visual field they could not. They could, though, identify the object by pointing. From this, Sperry concluded that language is processed in the left side of the brain.

He found, too, that objects shown to the left side of the brain can only be recognized by that side. If he displayed different symbols in the right and left visual fields and then asked the person to draw what they saw, they only drew the symbol shown in the left visual field. If he then asked them what they had drawn (not seen), they described the symbol in the right visual field. Objects originally viewed in the left visual field were recognized if viewed again in the left, but not if then viewed in the right visual field.

Look inside

Today, there are various ways we can examine brain structure and activity:

• A computed tomography (CT) scan uses X-rays and a computer to produce three-dimensional images of the brain. It shows the normal structure and can highlight damage, tumours and other structural changes or abnormalities.

• An electroencephalogram (EEG) monitors the electrical impulses produced by brain activity. It can reveal the person’s state of arousal (sleeping, waking, and so on) and show how long it takes for a stimulus to trigger brain activity or reveal the areas where brain activity takes place when the subject performs an action or is exposed to a stimulus.

• A positron emission tomography (PET) scan reveals the real-time activity of the brain by showing where radioactively-tagged oxygen or glucose is being concentrated. This is because the harder the brain works, the more oxygen and glucose it uses. It’s useful for seeing which parts of the brain are used for specific tasks or functions.

• Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) combines radio waves with a powerful magnetic field to detect different types of tissue, and produces detailed anatomical images of the brain.

• Magnetoencephalography (MEG) picks up the tiny magnetic signals produced by neural activity. This is currently expensive and not widely used, but it provides the most detailed real-time indication of brain function.

‘[Each hemisphere is] indeed a conscious system in its own right, perceiving, thinking, remembering, reasoning, willing, and emoting, all at a characteristically human level, and… both the left and the right hemisphere may be conscious simultaneously in different, even in mutually conflicting, mental experiences that run along in parallel.’

Roger Wolcott Sperry, 1974

For the first time, brain scans show psychologists which parts of the brain are involved in different types of activity and behaviour. Comparing brain scans of psychopathic killers, for instance, shows that they all have similar brain abnormalities (see Chapter 17).

DO YOU ONLY USE 10 PER CENT OF YOUR BRAIN?

Another popular psychology myth is that we only use 10 per cent of our brain. In fact, we use all of our brain, though not at the same time. Many of us don’t use our brain to its full potential most of the time, but all areas of the brain have a function and we do use those functions during the course of a day or a week.

You can always do more – when you learn new skills, your brain makes new connections between neurons to store knowledge and patterns of behaviour.

Knowledge and growth

In 2000, Eleanor Maguire at University College, London, used MRI scanning to compare the brains of London taxi drivers with those of a control group of men of similar age and profile. The taxi drivers had spent up to four years memorizing routes through the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Contents

- Introduction: What is psychology anyway?

- Chapter 1: What can we learn from a brain?

- Chapter 2: What drives you?

- Chapter 3: Don’t you have a mind of your own?

- Chapter 4: All for one or one for all?

- Chapter 5: Who cares what celebrities think?

- Chapter 6: Does attention spoil a baby?

- Chapter 7: Is morality natural?

- Chapter 8: Wasting your time in a daydream?

- Chapter 9: Would you do that again?

- Chapter 10: Why won’t you get up?

- Chapter 11: Can you be bored to death?

- Chapter 12: How cruel can you be?

- Chapter 13: Why are you wasting my time?

- Chapter 14: Why didn’t anybody help?

- Chapter 15: Are you the best ‘you’ that you can be?

- Chapter 16: Carrot or stick?

- Chapter 17: Can you spot a pyschopath?

- Chapter 18: What do you see?

- Chapter 19: Do violent images make you aggressive?

- Chapter 20: What did you come in here for?

- Chapter 21: Mind answering a few questions?

- Chapter 22: Does power corrupt?

- Chapter 23: What are you waiting for?

- Chapter 24: Who cares if you’re outbid on eBay?

- Chapter 25: Will smiling make you happy?

- Chapter 26: Is it really just a stage?

- Chapter 27: Is it worth doing the lottery?

- Copyright