- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Think Like a Philosopher is a fun introduction to the main concepts of philosophy, showing how the subject has a clear, practical, and vital purpose to our daily lives and thinking. Using a Q&A format and written in an amusing, easy-to-understand style, the author explains the philosophical arguments around questions such as: • Should I eat meat?

• Does God exist?

• Is capital punishment wrong?

• Will a new iPhone make you happy?A light-hearted read that sheds light on how the world's greatest minds have approached so many of the questions we face on a daily basis.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Think Like a Philosopher by Anne Rooney in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

How do you know how to think?

What is the best way to proceed with philosophical thought?

Question everything

Disciplined thinking takes nothing for granted. In the last chapter, we saw that the apparently simple question – which of two mountains is taller? – needs to be more clearly defined before it can be answered. In philosophy, all questions and all terms must be examined and defined before we can feel secure in proposing answers.

‘Philosophy is a discipline. You’ve got to discipline your thought. It’s not just making stuff up. And disciplining your thought is very hard to achieve.’

Tim Crane, Knightbridge Professor of Philosophy, University of Cambridge

The tools we use for philosophy are logic and reason; the arguments they produce can only be presented in language. This means that language itself falls under scrutiny. A good part of the philosophical work of the 20th century went into examining the foundations and reliability of language.

When you begin to look at philosophy, it can feel as if everything is constantly shifting, and questions multiply in front of you. It can be invigorating, or terrifying, or both. If you like certainty, philosophy might not be for you. But if you enjoy mental gymnastics and don’t mind the ground you have built your life on being wrenched from beneath your feet, it might be just what you’re looking for.

Dismantling certainty

Socrates said the only thing he was sure about was his own ignorance, and if he was wiser than other men it was because he recognized his ignorance. Socrates challenged people who thought themselves knowledgeable by asking them to define common concepts such as ‘courage’ or ‘justice’. He would then present counter-arguments, revealing inconsistencies or contradictions in whatever they said – it didn’t matter how they answered, he could always pick holes in their argument. Socrates intended to show that everything is more complicated than we are inclined to think, and accepting commonly-held beliefs without scrutiny is unwise. That was how he fell out of favour with the authorities in Athens. His way of teaching, known as the Socratic method, is still used. It is a dialectic method – a dialogue framed as a reasoned argument in which logical responses should lead the participants to the ‘truth’.

A fractal is a pattern that becomes ever more complex. The pattern replicates as it fragments, so you can see smaller and smaller details the closer you look at it. In mathematics, the area enclosed by a fractal is finite but has a boundary of infinite length. You can think of philosophy as fractal – every question leads on to further questions.

Thesis-building

Although Socrates used dialectic principally to unpick established beliefs, it has been used since his day to build knowledge. Again it works through a process of questions and answers, the answers prompting new questions that probe further and allow the participants to edge towards a deeper understanding.

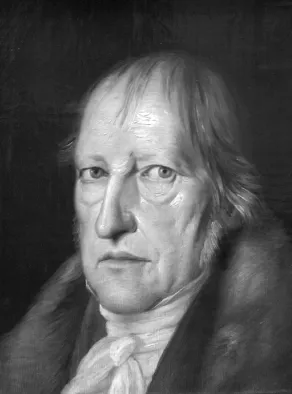

Dialectic is often associated with the 18th-century German philosopher Georg Hegel (pictured above), who presented it in a threefold manner:

• thesis: the idea or statement being proposed as true, such as ‘lying is wrong’

• antithesis: a reasoned answer to the thesis, contradicting it, such as ‘lying sometimes protects people from harm; therefore it can be good’

• synthesis: a new statement of the idea, revised in the light of the objections raised by the antithesis. In our example, it might be ‘lying when it is not intended to protect the person being lied to is wrong’.

The process can be repeated. The synthesis becomes the new thesis, and is examined and readjusted. By going through these steps, either in dialogue with someone else or by thinking the argument through yourself, you can scrutinize your ideas and make them more robust.

Court cases are tried by debate, with one side arguing in favour of the defendant and the other arguing the case for the prosecution. Skills and methods of philosophical debate are used to determine whether or not someone is guilty of the crime.

Start from scratch

In general, philosophers start with the work of earlier philosophers and use logic and argument to move the debate forwards. But this is not always the case. Philosophy is one of a few disciplines in which it’s possible to throw out baby and bath-water and run a new bath, starting from first principles. As long as the new model is logical and internally consistent, it stands a fighting chance of being taken seriously.

Martin Heidegger (1889–1976) and Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) both decided that for two thousand years, philosophers had got it all wrong and it was time to start again. Wittgenstein even stated: ‘It is a matter of indifference to me whether the thoughts that I have had have been anticipated by someone else.’ It certainly saves a lot of time that would otherwise be spent reading up on previous ideas, and can bring a freshness that allows completely new angles to emerge.

The role of logic

Logic is a highly formalized way of thinking and reasoning that involves using language as a precision tool. The first philosopher to set out the methods of logic was Aristotle, who lived in Athens in 384–322BC. He showed how we can start with two true statements that share one ‘term’, and draw another true statement from them using the terms they don’t share. The most famous example of this method – called logical syllogism – is:

All men are mortal. Socrates is a man. Therefore Socrates is mortal.

Here, the shared term is ‘men/man’ – it’s in the first two statements. Let’s reduce it to something more formulaic:

All As are B. C is an A. Therefore C is B.

The third statement remains true even when we remove the content (the details of men and mortality). This shows that the logic is valid: it is a formal relationship between statements. As long as the first two statements are true, the sequence will always work. Logic of this kind cannot be refuted – the difficulty for philosophy is filling in the terms (finding the statements) – that lead to useful and meaningful conclusions. This is where we need to be very precise and careful.

PLAYING DEVIL’S ADVOCATE

In philosophical debate, one person or group might play ‘devil’s advocate’, arguing for a view they don’t necessarily support just for the purpose of having a debate. From 1587 to 1983 ‘devil’s advocate’ was an official role. In examining the case for making new saints, the claim for the proto-saint was presented by ‘God’s advocate’ and challenged by the ‘devil’s advocate’. It was the job of the devil’s advocate to pick holes in God’s case. Socrates played devil’s advocate to uncover inconsistencies in the arguments of his opponents.

Suppose we were to say:

Killing people is wrong. Abortion involves killing people. Therefore abortion is wrong.

This is open to several challenges. The first is whether ‘killing people is wrong’ is a true statement – there might be circumstances in which killing people is not wrong. The second is whether abortion involves killing people: we have to ask when or whether a foetus counts as a person, and whether we can ‘kill’ something that is not independently alive. Although the logic is sound, the content is not. To practise philosophy, you need to keep a tight rein on both logic and content – to ‘discipline your thought’.

Where to start?

The French philosopher René Descartes (who, incidentally, also invented the Cartesian coordinate system used to draw graphs) famously said: ‘I think, therefore I am.’ It was his starting point for philosophy. He realized that he needed to start from something he could feel sure of, a secure proposition.

The position of certainty he came up with was his own existence, proved by his being able to think. Using Aristotle’s system of syllogisms, he could say:

Only things that exist can thi...

Table of contents

- Title

- Contents

- Introduction: What is philosophy for?

- Chapter 1: How do you know how to think?

- Chapter 2: What do we mean by ‘reality’?

- Chapter 3: What do you know?

- Chapter 4: When is a biscuit not a biscuit?

- Chapter 5: Tea or coffee?

- Chapter 6: Is there a ghost in the machine?

- Chapter 7: Who do you think you are?

- Chapter 8: Bad things happen – but why?

- Chapter 9: What goes around comes around – or does it?

- Chapter 10: Will a new iPhone make you happy?

- Chapter 11: Would you want to live forever?

- Chapter 12: Can you choose to believe in God?

- Chapter 13: Does a dog have a soul?

- Chapter 14: Can you say what you mean and mean what you say?

- Chapter 15: How do you do the right thing?

- Chapter 16: Should we ever burn witches?

- Chapter 17: Does ‘I didn’t mean to’ make a difference?

- Chapter 18: Is all fair in love and war?

- Chapter 19: Could we make a perfect society?

- Chapter 20: Are some people more equal than others?

- Chapter 21: Should we rob one Peter to pay several Pauls?

- Chapter 22: How do you define a virtuous life?

- Chapter 23: Can a robot think for itself?

- Chapter 24: Are we being watched?

- Chapter 25: Should you rock the boat?

- Chapter 26: Is it better to give than receive?

- Chapter 27: To be, or not to be?

- Copyright